In 1997 Jim Isermann slipcovered a Minimalist cube. The rest is queer art history

Jim Isermann’s art of the past 40 years comprises a body of hybrid work celebrated as crucial to the emergence of design as a discipline as powerful as painting and sculpture. Despite misplaced historical qualms about design’s capacities, and along with artists as diverse as Scott Burton, Jorge Pardo, Pae White and Andrea Zittel, he has been instrumental in changing the terms of the conversation.

In a new monograph on Isermann’s art published this month by Radius Books, I argue that the change is rooted in a radical commitment to domesticity — the private shelter and refuge from hostility provided by the home — that positions Isermann as an avatar of queer culture. This excerpt from the book has been edited for context and clarity:

In 1997, Jim Isermann began production of a group of textile sculptures. Most took the form of a cube. We’re not talking the cubes of Cubism here. For sculpture, the cube is Minimalism’s echt form. As a composition it offers no formal hierarchy — neither up nor down, no distinctive front or back or sides, nothing that yields greater importance to one point of view over any other. The cube confirms formal and structural assumptions of equilibrium.

Which is not to say that a cube is without any but formal meanings. Isermann’s art insists on evoking history and its social complexities.

For his cube sculptures, begin with “Die,” conceived in 1962 by architect and sculptor Tony Smith and later fabricated in oiled steel. Smith’s cube sculpture, six feet on a side and thus the relative height of a standing person, was inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s famous Renaissance drawing of the Vitruvian Man. His idealized male figure features legs spread wide to form an equilateral triangle. Outstretched arms inscribe his four limbs within a perfect circle and a complete square. Triangle, circle, square — throughout history, abstract representations of sacred geometry are found in global architectural practices.

)

In a tool-and-die shop, the die is the female component of the perforated tool that punches sheet metal into a shape. The human-scale “Die” sculpture is a void that displaces space. It evokes the ancient architectural construction known as a cenotaph — the cubic burial marker that remembers and venerates a missing body. (The artist once quoted poet W.H. Auden in reference to human mortality: “Let us honor if we can the vertical man, though we value none but the horizontal one.”) The funerary association of Smith’s sculpture is inseparable from the violent social climate of the 1960s, an era marked by blood-soaked civil rights tumult, the American war abroad in Vietnam, and political assassinations at home.

Similarly unavoidable is the depersonalized quality of the blank form of brute steel: Smith’s cube reveals no marks of the artist’s hand. Indeed, the artist did not fabricate “Die.” He picked up the telephone instead, called the Industrial Welding Co. of Newark, N.J. (“You specify it; we fabricate it”), gave them the specs (“a six-foot cube of quarter-inch hot-rolled steel with diagonal internal bracing”), and ordered up a sculpture to be manufactured.

The artist’s hand as a signifier of unique, individualized identity — of emotive autobiography — was highly prized in the Abstract Expressionist art that immediately preceded Minimalism. A newly emergent commercial market in homegrown painting and sculpture, which had been elusive for the first half of the so-called American Century, also made an identifiable hand an authenticating mark of monetary value. “Die,” in its plainly intentional erasure of the artist’s hand, ruminates on mortality — not just about a single, particular death, the passing of a hero or notorious villain, as sculptures and cenotaphs had done throughout history, but death as a condition of humanity itself, and of the perishable passions and commitments reflected in a culture’s evolving, ever-changing artifacts. Abstract Expressionism was pronounced dead.

“Die” is a Minimalist fountainhead. In its aftermath, the cubes came fast and furious.

“Cubi I” (1963), the first of David Smith’s final series of metal sculptures, is constructed of cubes of stainless steel welded together. Donald Judd, starting in 1965 with rectangular stacks that alternate solids and voids of equal size, made cubic boxes of metal, plywood or concrete. Larry Bell’s “Cube” (1966) of vacuum-coated glass, which infused the form with a shifting halation that transmits, absorbs and reflects atmospheric colored light transmuted the rigid, rational form into an organic perceptual conundrum.

Eva Hesse’s “Accession” series (1967–68) is composed of cubes of galvanized steel or transparent fiberglass open at the top, perforated on the sides and punctured by tens of thousands of short, sensuous, probing rubber tubes. Chris Burden’s “Five Day Locker Piece” (1971) wedded performance art to the cube, beginning with a found example — a common two-foot-square student locker at school — inside of which the artist locked himself in a harrowing human endurance test.

Sol LeWitt’s mathematically determined “Incomplete Open Cubes” (1974–82) laid out a dispassionate, paradoxical demonstration of all 122 ways of, as he put it, “not making a cube, all the ways of the cube not being complete.” Jackie Winsor’s “Burnt Piece” (1977–78) subjected a cube constructed from wood, wire mesh and cement to a bonfire. Charles Ray’s “Ink Box” (1986) fabricates a perceptual and conceptual enigma composed from a glossy black cube, three feet per side, of crisply painted steel with one shimmery, quivery face that only slowly reveals itself as a shallow meniscus of messy black liquid printer’s ink.

There are more. This proliferation of Minimal and Post-Minimal cube sculptures over a quarter-century of American art is nothing short of stunning. Such diverse abundance would seem to have exhausted the form — which is all the more reason that Isermann’s decision to take it on in the 1990s is so impressive.

And all the more revealing about what his new sculpture was up to.

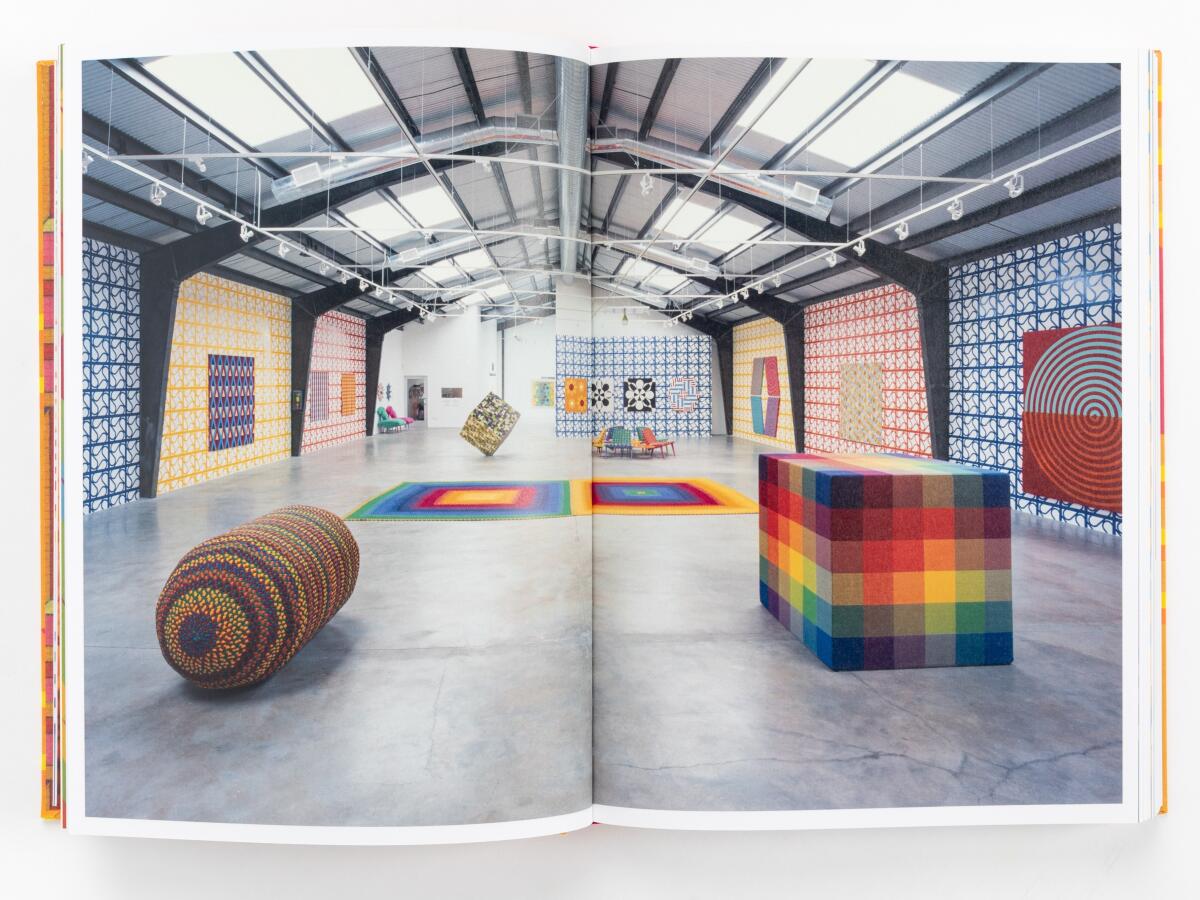

In fact, a sense of exhaustion, of being worn out and used up, is intrinsic to his 1997 “Untitled (Cubeweave).” Isermann made the sculpture from a handloomed, rainbow-colored plaid textile that he fitted over a 52-inch box of solid foam. In other words, the sculpture is composed of a slipcover fitted over an iconic Minimalist cube.

Slipcovers are what you put over a tired sofa or tatty armchair to refresh and resuscitate the worn-out object’s useful life. After the quarter-ton steel “Die,” Isermann’s light textile cube performs a resurrection — a theme with a long history in sacred art, but here avowedly secular and unequivocally domestic in form.

Isermann made 10 of these slipcovered-cube sculptures, two large and eight smaller ones at 25 inches on a side. Their wit belies the underlying seriousness of the move, which is at once simple, unexpected, labor-intensive and conceptually powerful. He approached an established, even archetypal artistic form the way one might consider any treasured family heirloom, and he made a covering to at once protect and renew it. In the process, he queered its legacy.

The domestic realm animates Isermann’s art. He had spent the prior half-dozen years teaching himself a number of homespun craft techniques, gleaned from how-to handbooks. Stained glass panels, wall hangings of pieced fabric, woven textiles and hand-braided rugs are techniques that embrace a homey, lived-in, DIY aesthetic for objects, crossing art and design, functional and not.

The textile he wove for “Untitled (Cubeweave)” is a multicolored plaid. Essentially, plaid is made from the woven intersection of stripes at right angles. His sculpture’s stripes are composed from the six colors of the rainbow, which can be seen as solid hues by following the diagonal from the upper right to the lower left corners on the cube’s five visible faces. As the colored stripes intersect, 30 blended hues emerge.

In the 1990s, when Isermann made his cube sculptures, the cold, hard, assertive edge of historic Minimalist form was also being actively critiqued as inherently masculine. As sculpture, the contradictorily warm, soft, seductive edge in his “Untitled (Cubeweave)” butts up against that critical analysis, handily queering it.

The eccentric slipcover’s elaborate, handmade plaid is abstract and possesses no symbolic attributes, but it nonetheless evolves from a crossing of rainbow flags. Designed in San Francisco at the behest of Harvey Milk in 1978 by gay activist Gilbert Baker, and well on its way in the ‘90s to becoming a global symbol for LGBTQ pride, the embedded rainbow flag is drawn from the hubbub of popular culture rather than the stillness of the museum. Add the high art pedigree of Ellsworth Kelly’s Minimalist Spectrum paintings, and Isermann’s slipcovered cube is queer to its core.

Here’s an irreducible fact: Normative heterosexuality suppresses the domestic realm as a locus of value, intellectual insight and cultural power. In vibrant contrast, Isermann’s queer, slip-covered, DIY cube joyously expresses it.

Growing up gay on the shores of Lake Michigan in suburban Kenosha, Wis., America’s putative heartland, Isermann is no stranger to the limiting restrictions of gendered cultural codes. High on the list is the deeply ingrained, even pathological insecurity about masculinity that permeates societies based on a patriarchal principle.

Homophobia is a dimension of misogyny. Viewing women as occupying a subordinate social position coincides with repression of male homosexual practices — that is, with a man “playing the role of a woman” with another man or using another man “like a woman” — a culturally ingrained sexism of global sweep.

Consequently, the domestic world looms large as a platform for the flourishing of queer culture. House and home, problematic as a traditional sphere of activity and base of operations within a hostile society, becomes a charged place that must be invented from scratch — then reinvented over again. Isermann’s fervent embrace of design, crafts and do-it-yourself projects more directly associated with domestic hobbyists than with professional producers of studio art, like painters and sculptors, is an unmistakable and audacious act of opposition.

To be sure, Isermann’s slipcovered Minimalist cubes do not operate as narrative commentaries on issues of the day. Subject matter in his work is neither topical nor politically partisan. Instead, misogyny and homophobia are inherent back stories to the engaged choices he makes as an artist.

The radical domesticity fueling Isermann’s art is, unsurprisingly, reflected in the artist’s own home life. In 1997, he acquired a ruined prefab Steel House in Palm Springs designed a generation earlier by Modernist architect Donald Wexler. The house, then derelict, was once the epitome of avant-garde domestic design. It had been factory fabricated in modular units that were trucked to the site and assembled, crafted from steel to withstand high desert winds and from glass to maximize sunny transparency.

Restored with Isermann’s partner, David Blomster, to its former pristine beauty over the next several years, the Steel House fulfilled Le Corbusier’s dictum that “Une maison est une machine-à-habiter” — a house is a machine for living in. That the restoration project to refresh and resuscitate a worn-out domestic residence’s useful life coincided with production of the queer, slipcovered Minimalist sculpture “Untitled (Cubeweave)” is only to be expected.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.