A groundbreaking Chicano series, stored 50 years in a garage, reemerges

Every so often, Frank Cruz would walk into his spacious garage in Laguna Niguel and contemplate the boxes filled with things old and unused: tax returns, clothes and paperwork from his days as a Chicano studies professor, TV news reporter and anchor, co-founder of the Spanish-language network Telemundo and of a pioneering Latino-owned insurance company. Not to mention notes from the many boards he’s served on, including the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

But there was one particular big blue box — between another containing his now-adult children’s baby teeth and one with a daughter’s wedding dress — that always gnawed at him. Its label read: “Chicano Series.”

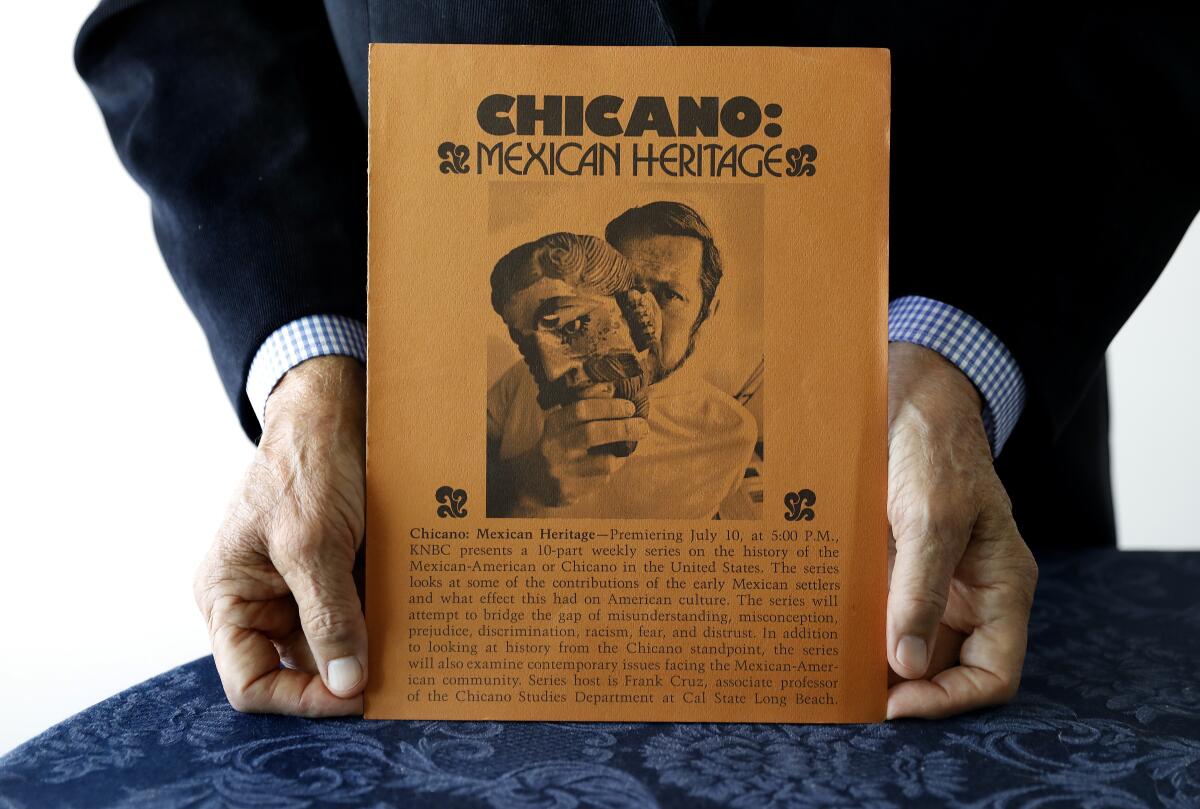

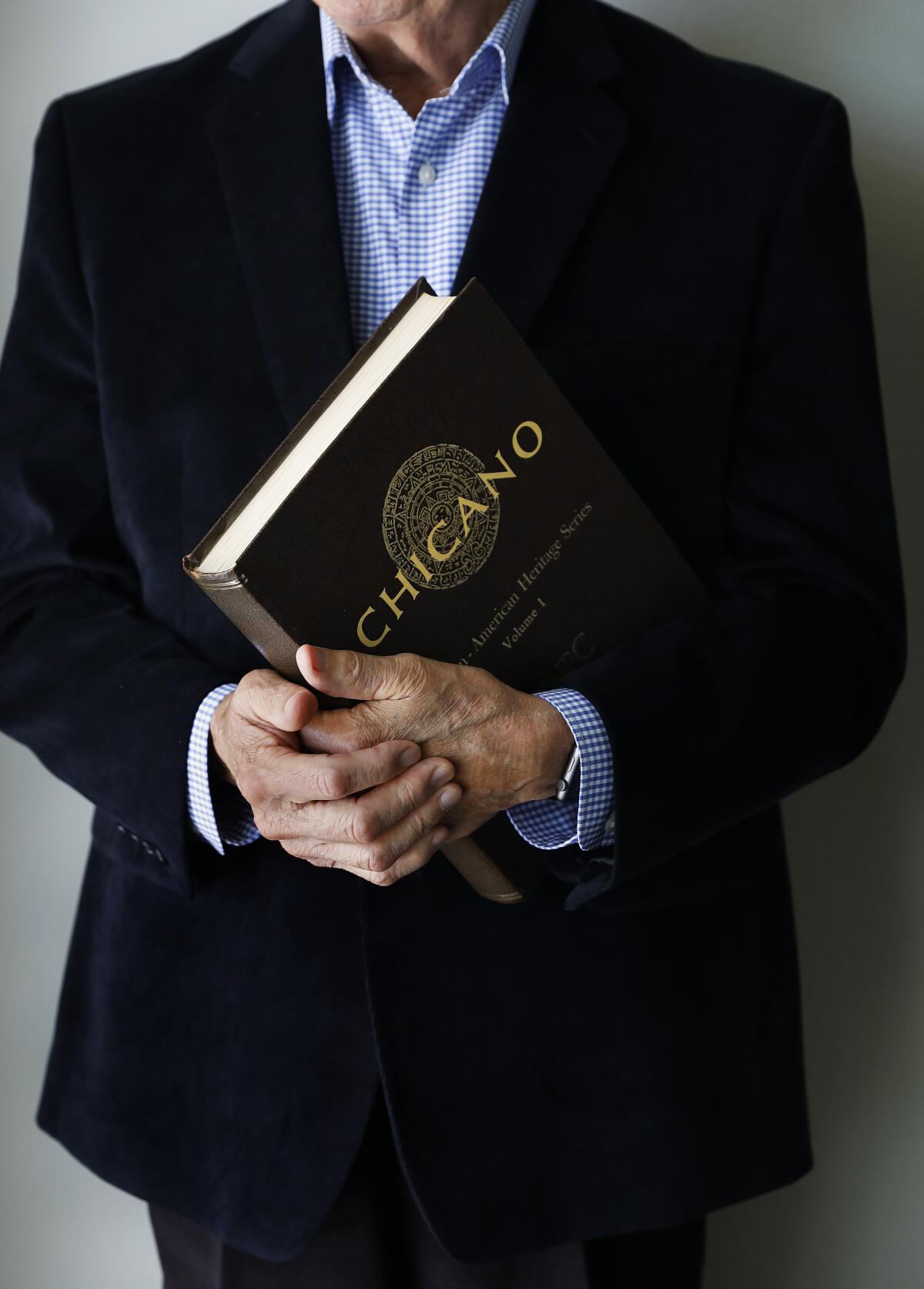

Inside were nine 16-millimeter film reels of “Chicano I & II: The Mexican American Heritage Series,” the television show that first aired on KNBC-TV in Los Angeles in July 1971. The series, hosted by Cruz when he was in his early 30s, also played on sister stations in Chicago, New York, Cleveland and Washington, D.C.

For 50 years, the reels remained in his garage, largely untouched.

On a recent August day, Cruz, now 82, thought to himself as he had dozens of times before: “Pendejo, you better do something about those films. It might be too late.”

And he did. His contacts led him to a film archivist at USC who digitized the film and created a website for them. For the first time since they aired and reran in the early 1970s, nine of 20 episodes from the Chicano series are now publicly available on the website for USC’s Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive. (No film exists from the “Chicano II” portion of the series, and Episode 6, titled “The War Years,” was missing from Cruz’s first-volume holdings.)

“I was prepared to hear that [Dino Everett, the archivist] wasn’t able to do it because the film was too brittle, that they had broken and that they were no good because the images fade,” says Cruz. But a couple weeks later, “after 10 candles and a prayer to Santo Niño de Atocha, he called me and said, ‘Frank, I’ve been able to transfer them.’”

Cruz was elated. “We’re preserving history.”

They challenged boundaries

The East L.A. walkouts of 1968, followed by the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., both beloved by much of the Latino community, happened months apart. Then came the Chicano Moratorium of 1970 and the killing of Ruben Salazar, an esteemed reporter for the Los Angeles Times.

Out of this period of social and political activism, and fed up with the stereotypical depictions of Latinos in media, Sal Castro, a key leader in the historic walkouts, and Julian Nava, the first Mexican American voted to the Los Angeles Board of Education, approached Los Angeles’ KNBC-TV with a pitch: to create a show that explored issues facing the Mexican American community and examined history and culture from the Chicano perspective.

The station agreed to air the show. Cruz, a former Lincoln High School teacher and colleague of Castro’s, who was teaching history at Cal State Long Beach at the time, agreed to host the series after Castro declined. Cruz’s “yes” would change the course of his professional life — after the 1971 series reran in 1972, the news director of KABC-TV called Cruz offering him a reporter job covering L.A.’s Latino community.

Frank Cruz always told other people’s stories. Now, he tells all in his memoir about his days as a reporter, Telemundo co-founder and everything in between. He carved paths for others along the way.

“Chicano I & II” episodes were put together by professors, historians and experts — many of them founders of their universities’ Chicano studies departments, including UCLA, Stanford, San Jose State and San Fernando Valley State College (now Cal State Northridge). Among the topics they examined were the history of migrant workers and Chicano labor activities, economic repression and education inequality, as well as the many cultural and other contributions of their Mexican ancestors to the Western world,

“‘Stereotyping in the Mass Media,’ I mean you could write a headline with that today!” Natalia Molina, a professor of American studies and ethnicity at USC, says about one of the episode’s titles.

The series, she says, was trying to show that “Mexicans aren’t docile, that they’re people. They’re like you and I. They live lives in three dimensions. They have families. They create. They were just trying to bring humanity to what we think of when we think of the Latinx population. And that is still something we’re struggling to do today.

“No one had done anything like it,” she adds. “The series was cutting-edge then and I think, unfortunately, it’s cutting edge now.”

Many of the show’s guests and interviewees spearheaded the issues and topics covered and were among the first in their field, such as Nava or Ricardo “Richard” Romo, an author and urban historian whom Molina, a 2020 MacArthur fellow, credits for laying the groundwork for her research.

“These are the people that did that original work for us,” she says, “and challenged all kinds of boundaries.”

Romo, the urban historian, remembers relating to the educational issues raised in the show.

“A lot of us had experienced some of the things that frustrated these students,” says the Texas-born-and-raised scholar. “The libraries had no books about our history. The teachers were driving in from the suburbs and didn’t understand a lot of the things happening in our communities. … [They] told us, ‘You can’t speak Spanish in the classroom or in the schoolyard.’

“The worst part is that there were a lot of good teachers, but many of them didn’t think enough of the students to encourage them to go to college,” Romo says. Only two from his graduating class of 400 went to a four-year college. He was one of them.

Groundbreaking as the series was, viewership numbers from that time aren’t easy to find. But based on its 6 a.m. air time, the numbers were likely low. It was “not a popular hour,” recalls Romo. It was frustrating.

“It was like, ‘We want to do this, but we can’t give you a good, prime hour where we have the highest advertisers,” says Romo, stopping himself from being too critical because at the day’s end, the greenlight was given to produce “one of the first shows of its kind in the whole country.” He just wishes that today’s technology and social media existed then to expand the viewership.

Now it does.

The archivist behind the digitizing

Dino Everett is a self-described optimist.

A longtime archivist at the USC Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive, he’s learned through the years “that one way or another, even if something comes to me in horrendous condition, I can usually get something out of it.”

Luckily, Cruz had stored the film reels in the best way possible, albeit inadvertently: in cardboard boxes, which act as an insulator, versus exposed metal cans.

Residential homes, Everett explains, aren’t usually climate controlled, so film stored in metal cans are susceptible to temperature changes. “The variation, the back and forth between the hot and cold,” he says, “is what really damages the film.”

Once in his hands, Everett took the films off their metal reels, ran them through a cleaning machine, then put them through a film scanner called a Kinetta before sliding them through a restoration software program to clean up slight imperfections like dust and light flickers. After two weeks and more than 60 hours, all nine episodes had been digitized.

“[Frank] was thrilled that I was able to scan them,” he says. “I wish I could say that it was because of my expertise, but they were in really great shape.”

The show, notes Everett, was done in kinescope — the process of recording a live TV broadcast onto film by pointing a camera at a screen or video monitor as it played the footage; it’s how stations would preserve and duplicate their live programming and send it to affiliates.

The process was replaced with the advent of videotapes in the 1950s, so it was rare for TV stations in the early ’70s to still be using it. But videotapes then were pricey. “It was actually cheaper to make black-and-white kinescopes than make full-colored videotapes,” says Everett.

On a recent September afternoon via phone, Cruz struggled to answer the question: Why didn’t you digitize the film sooner?

After a brief silence, he responded: “Could’ve, would’ve, should’ve.”

“Chicano I & II: The Mexican American Heritage Series” can be viewed on the website of the USC School of Cinematic Arts’ Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive at: uschefnerarchive.com/chicano.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.