Commentary: UCLA is selling a Picasso. Why that’s a good thing

While the Metropolitan Museum of Art is treating its collection like a bank, UCLA’s Hammer Museum shows a smarter approach to deaccessioning art.

The fall auction season is underway in New York, and, as expected, several art museums have sent significant works to the block.

At least one surprising consignment, a marvelous 1930 Picasso painting unseen in public for six decades, is a fine example of prudent collection management that stands to substantially strengthen its owner’s educational mission.

Unfortunately, at the other end of the spectrum, another museum offers a dismal example of exploiting its art collection as a virtual bank. This move is so egregious that it threatens to harm the entire museum field.

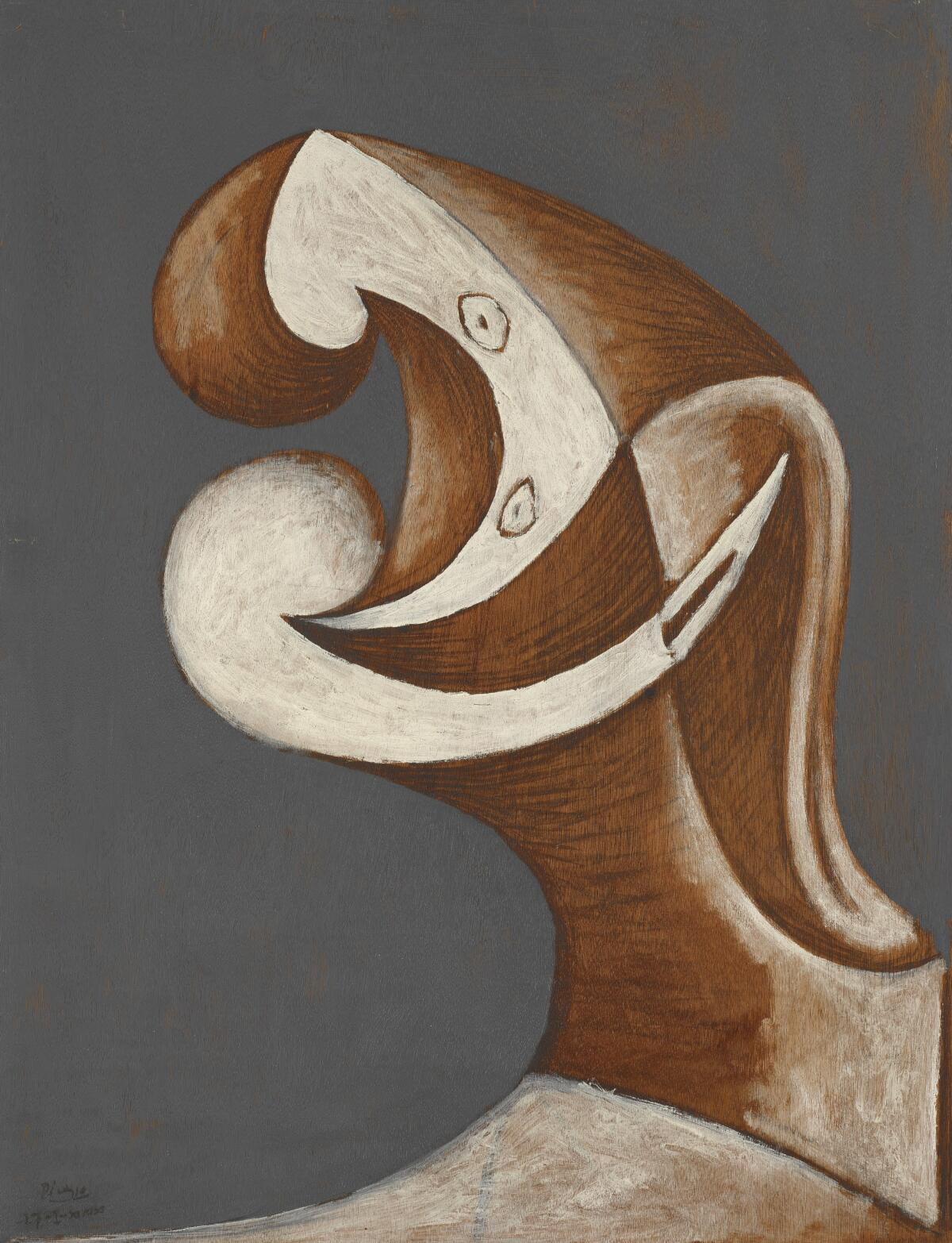

The fine surprise comes from the Regents of the University of California, which is expected to announce today that it is deaccessioning Picasso’s head of a woman, “Profil,” to establish a fund for the acquisition of drawings, prints, photographs and other works of art on paper at the UCLA Hammer Museum and its admired Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. The painting, given to UCLA in 1959 but languishing in storage since a 1961 exhibition in honor of the artist’s 80th birthday, is estimated to bring between $6 million and $8 million at the upcoming Nov. 11 sale at Christie’s.

The dismal example is from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Already sold are 168 Civil War-era photographs by Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, Timothy H. O’Sullivan, George N. Barnard and others, plus Modern photographs by Anne Brigman, Robert Frank, Eadweard Muybridge and more. In November, important graphics by Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella and other artists will join them.

All these photographs and prints are duplicates of works in the Met’s collection, according to the museum. That makes the curatorial decision to winnow them appropriate. A museum specializing in prints or photographs might want to keep duplicates, since analysis of slight shifts or changes in print production can be revealing for scholarship. But the Met is a general, encyclopedic museum, so its priorities lie elsewhere.

Where the problem arises is in the planned use for the funds raised from the sales. (The Civil War pictures, sold Oct. 7, brought in about half a million dollars.) Rather than sequester the money for future acquisitions, which is routine, the Met told Christie’s it would be spent on daily operations — mostly salaries, it appears — “in consideration of revenue losses from the ongoing pandemic.”

That’s appalling.

For one thing, the claim of desperate financial need is at best disingenuous. America’s billionaire class — which includes the Met, given its prepandemic endowment of roughly $3.6 billion — has fared spectacularly well over the last 18 months. The Institute for Policy Studies reported in August that America’s 708 private billionaires have grown $1.8 trillion richer during the pandemic.

And the Met? When COVID-19 shut down museums in March 2020, the Met projected a likely $150 million revenue shortfall. That hefty figure has been widely repeated in the press ever since. Unreported before now, however, is the massive 33% spike in the Met’s endowments since then, which a museum spokesperson told me are now pegged at $4.4 billion.

That’s what I’ve dubbed the pandemic dividend — this one totaling $800 million. The museum is crying shortfall while neglecting to mention windfall.

Call it the ‘pandemic dividend’: A rising stock market helped endowments rise as much as 40%, yet museums are still selling pieces of their collections.

Institutional budgets and endowments, both restricted and unrestricted, can be complicated. The New York attorney general’s office suggests a 7% cap on the income a museum might draw from its endowment. As the pandemic exploded, the Met bumped up its annual draw to 5% from 4.9%. If it were to temporarily hit the AG’s cap on its newfound wealth, that daunting crisis shortfall would largely evaporate.

What the Met is doing is not traditional deaccessioning, either, although it’s usually misrepresented in the media as such. What the Met is doing is monetizing its collection.

Deaccessioning is the removal from a museum collection — often but not always followed by sale — of art that is damaged, inferior, duplicative or otherwise outside the museum’s mission. The aim is to refine and elevate the permanent collection; so, if it gets sold, the income is reserved for future art purchases. It’s a long-standing best practice in the profession, and it happens all the time.

Monetizing, on the other hand, is selling collection art to raise money to pay operating bills or capital expenses — just like any commercial gallery or other for-profit business might do. For a tax-exempt charitable institution like an art museum, it’s a worst practice.

The clamor for monetizing has been rising for years, mostly from museums of Modern and Contemporary art, where the market booms and makes headlines. They’re egged on by a few clueless art lawyers and errant academics. Now, the mighty Met has added to the noxious chorus.

How did we get to this low point? Financial panic erupted in April 2020 after a pandemic-induced stock market crash. That caused the Assn. of Art Museum Directors, the leading art museum industry group, to open a two-year allowance for members to engage in the practice. Before that, monetizing had always been forbidden.

Markets, though, quickly recovered — and then steadily climbed over the last year and a half. Even though unexpected pandemic dividends have been piling up on museum balance sheets coast to coast, the rattled-AAMD error has not been fixed. Opportunistic museums in Baltimore, Brooklyn, Syracuse, San Diego, Palm Springs and elsewhere decided not to let a good crisis go to waste. They cashed in art.

And now the Met may be putting its unmatched clout behind hopes for a more permanent change.

The museum has reported an average income from deaccessioning art in recent years of about $13 million annually. Salaries for direct collection care run about $15 million, according to Director Max Hollein. Sales income could pretty much cover that operating expense — if only monetizing wasn’t banned.

As America’s flagship museum, the Met’s monetizing imperils the rest of the fleet. Every museum in the nation now faces the grim possibility of a trustee demanding of its director: If the Met can do it, why can’t we?

Ironically, university art museums like the Hammer are among the most vulnerable. Many maintain valuable collections on behalf of schools whose administrations might suddenly cast an eye on a revenue source, much to their museum directors’ horror. The Met has just made their lives harder.

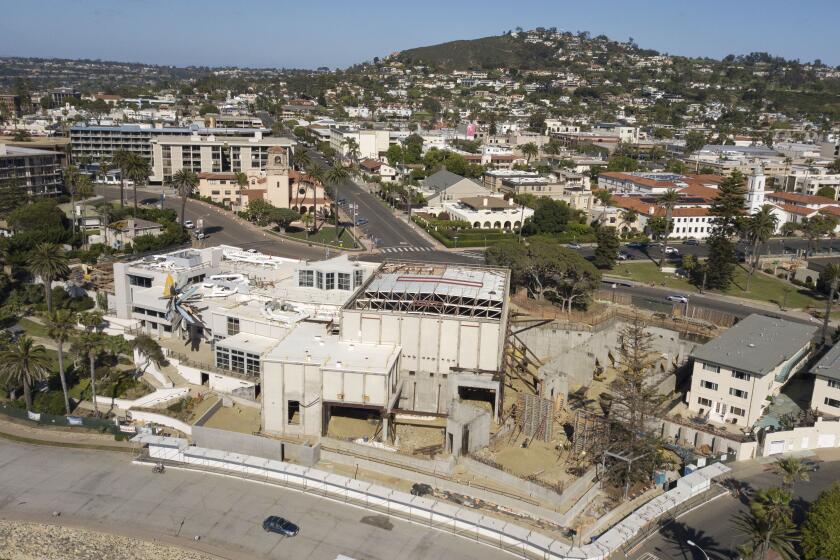

That’s one reason UCLA is a special bright spot. Early next year, the Hammer will unveil a newly expanded study and storage facility for the Grunwald Center, complete with a first-ever dedicated exhibition gallery for works on paper. Income from the deaccessioned painting is an unexpected boon.

“Profil” is a so-called Picasso “bone painting,” a rare abstraction that’s part Cubist and part Surrealist. The animated, interlocking comma shapes of the head both smile and frown at once, the figure’s sensuous curves shrouded in somber hues of brown and mottled white against an elegant if dour plane of gray.

The day before he painted it, Picasso made a looser, slightly rougher version with the colors reversed — the life-size head in gray and white and the background brown. Perhaps a study for the slightly larger UCLA picture, which is 26 by 20 inches, it’s a prize in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum.

The precise subject is unknown. But “Profil” may well be a sort of two-in-one portrait, reflecting the turmoil of an unsettled period in the middle-aged artist’s secret affair with his 20-year-old mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, during his combative marriage to Russian ballerina Olga Khokhlova.

The Picasso falls outside the Hammer’s collecting mission, which focuses on art made after World War II. It’s also not a work on paper, which the Grunwald collects, nor a sculpture, like those in UCLA’s Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden. Deaccessioning makes sense. The museum collections will grow, the public will benefit.

UCLA has gotten the blessing of the Picasso donor’s heirs, according to Hammer Director Ann Philbin and Grunwald Director Cynthia Burlingham. The painting was a 1959 gift from prominent collector Stanley Newbold Barbee, shortly before he decamped to Hawaii from L.A.

With his brothers, Barbee had grown rich on the Southern California franchise for Coca-Cola. A yachtsman, he hired architect Robert V. Derrah in 1936 to design Coke’s now-landmark Art Deco bottling plant downtown on South Central Avenue. The Pop design, a Streamline Moderne pastiche of a massive cruise ship complete with porthole windows and a captain’s bridge, turned the classic motif of a ship in a bottle inside out, instead putting bottles in a ship.

Other fine paintings Barbee once owned have ended up at the National Gallery of Art (a Eugène Boudin seascape) and, yes, the Met (a Camille Pissarro cityscape).

Yes, the Grove and the Original Farmers Market are not far away. But there are other places to see, to walk, to eat.

In an ideal world, selling museum art would hardly happen at all. Once an object left the private marketplace and entered a public collection, it would stay there.

And if it no longer fit? A simple transfer of the unwanted Picasso to another relevant and nearby museum — the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, for instance, which has 17 others, including one from the same year — would add further depth and nuanced context to a major artist’s public representation. The group of 168 Civil War photographs would make an exceptional contribution to, say, a museum at a New York college with a strong program in American history or documentary photography.

We don’t live in an ideal world, of course, but such sales do mean the public loses exceptional cultural assets. Neither LACMA nor a college museum has the wherewithal to shell out cash to buy those works, which inevitably vanish into private hands.

Sequestering deaccession income for future art purchases is the next best thing, which is one reason the compensation is a long-established museum norm. UCLA’s thoughtful plan to deaccession the Picasso to benefit future acquisitions is exemplary, while the Met’s monetizing is dangerously crass.

An old department store building was thought to be unusable as a museum, but the film academy has proved different.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.