Review: Anthony Davis’ ‘Restless Mourning’ boldly ventures where other composers fear to go

An anniversary of 9/11 arrived Saturday, and the question was the same as it has been for 20 Septembers: Whence America’s memorial music? Ten days after the bombs hit, the German music director of the New York Philharmonic could think of nothing more relevant to play than Brahms’ “Ein Deutsches Requiem” — moving music, yes, but a German-language requiem written for another century in another place, the composer mourning his mom’s passing.

The 20th anniversary of 9/11 and what does the Metropolitan Opera, back in its Lincoln Center opera house for the first time since March last year, perform but Verdi’s Requiem, nearly as old and foreign as the Brahms. This is all the more unconscionable given that a shaken Christopher Rouse — teaching at Juilliard, yards away from the Met and horrified by the attack on the World Trade Center — wrote the awe-inspiringly great American Requiem in its wake.

For the record:

3:22 p.m. Sept. 15, 2021A previous version of this review incorrectly said the concert was at First Congregational Church.

For the most part, artists responding to 9/11 felt they had little choice but to play it politically safe in its jingoist aftermath, and little consequential 9/11 art seems to have gotten made. Another notable, but still safe, exception in music was John Adams’ “On the Transmigration of Souls.” The atmospheric orchestral work transformed the concert hall into a spiritual, safe space. It won a Pulitzer Prize; although a pi´èce d’occasion, it has few opportunities for performance.

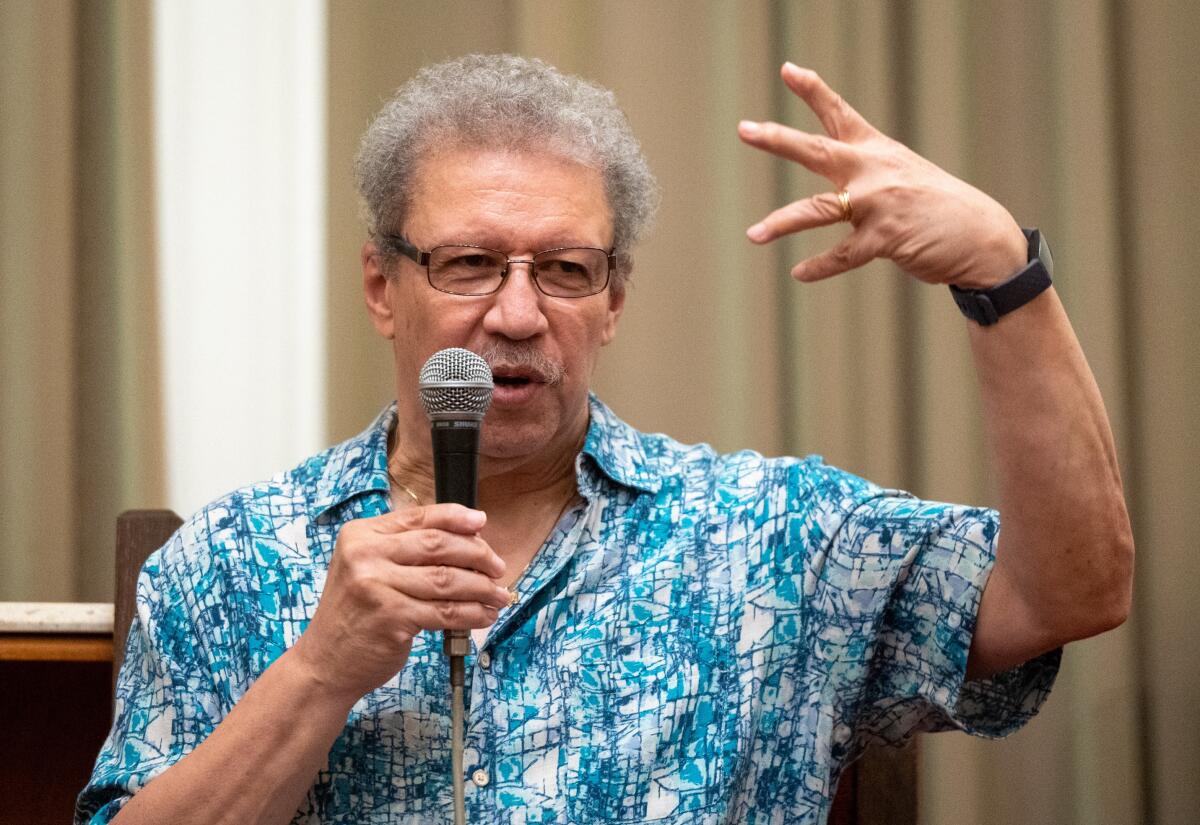

There is a third exception, an astonishingly daring one from 2002 by a prominent American composer, that fell much deeper through the cracks. In its 9/11 tribute program Saturday night, the Santa Monica new music series Jacaranda dug out Anthony Davis’ “Restless Mourning” at First Presbyterian Church for its first concert since pandemic closures hit. Hiding in what should have been plain sight, this grippingly poetic and politically candid 9/11 response hits home. It could have been written the day before yesterday.

Davis is the composer of such cogent operas as “X,” “Amistad” and “The Central Park Five.” They are instances of music theater that do not tell the stories of Malcolm X, the slave ship Amistad or youths of color falsely accused. They are the stories, conjuring the mysteries and the forces behind the narrative. You leave the theater not so much informed as enlightened. You leave shaken.

Likewise, “Restless Mourning” — commissioned by the Piccolo Spoleto festival in Charleston, S.C., and written for chamber chorus and chamber ensemble — opens with a setting of poetry by Quincy Troupe. The late-summer sky over New York City the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, cloudless and cerulean. But there are blues, and there are blues — the blue of a beautiful Swedish woman’s blue eyes and a blues singer’s blues, the blue of a policeman’s uniform and the unreachable blue void of somewhere beyond the stars. Was the smoke from the flaming Twin Towers tinted blue?

In the ghost-haunted second movement, using a text by playwright Allan Havis, we hear the voice of “the pilot of the bold 767.” He had taken his daughter to school and quarreled with his wife earlier that fateful morning. He then becomes “the pilot of Allah’s 767.” One pilot is the other pilot. Each believing to have been on a mission of innocence, noble and good, they are turned to “dust and vapor.”

Ghosts inhabit the third movement, as well. The World Trade Center was built on ground that had been a graveyard of slaves, many of whom were Muslim. Their ghosts, in another Troupe poem, greet the blackened and incinerated ghosts of those killed on Sept. 11.

The text from the finale is taken from Psalm 102. Taunted by enemies, derided by those who use his name, David eats ashes for bread and mingles tears with his drink. “Let this be recorded for a generation to come so that people yet unborn will praise the Lord.”

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

Davis mentioned at the pre-concert talk Saturday that his commissioners recommended eliminating the potentially controversial two central sections. The Psalm, which he set as a gospel, might well stand alone, his publisher figured. Davis stuck to his guns, and until Saturday, “Restless Mourning” had only one performance, in Omaha in 2007, around the premiere of his opera “Wakonda’s Dream.”

Blues permeates “Restless Mourning,” never in obvious ways. Nothing in the work is obvious, which alone separates it from the typical 9/11 memorial. Davis’ harmonic vocabulary is elaborate, unpredictable, his own. Instrumental colors, bright or dim, are made of many hues. There are electronics used for their mystery-making. The vocal writing can be declarative and songful at the same time. Solo singers and grouped voices do not dramatize text but rather take it to other realms. Davis ends not somberly but with the glorious hope that mingled ghosts might illuminate the skies in a manner far different than what the terrorists produced. Blue has become, once more, cerulean.

The piano is a stellar member of the instrumental ensemble, which also uses electronics. The keyboard writing is jazz-infused, Davis a brilliant improvising pianist. The urgent pianist for this performance, Althea Waites, it so happened, had booked a ticket on the American Airlines flight from Boston to LAX that was hijacked. Shortly before, she decided to come a day earlier and changed to the same flight on Sept. 10, 2001.

Anthony Parnther, the music director of the San Bernardino Symphony and of the Southeast Symphony and Chorus in L.A., led a superb performance, featuring the choral group Tonality and some of L.A.’s finest young instrumentalists — exactly the performance “Restless Mourning” needs. I hope Jacaranda can release this as a recording.

For the first half of the program, the Lyris Quartet looked at 9/11 through the mournful yet luminous lens of Joan Tower’s “In Memory,” also from 2002, and Steve Reich’s you-are-there visceral “WTC 9/11” for string quartet along with two more pre-recorded string quartets and altered voices of 9/11 witnesses. It was composed for the 10th anniversary of 9/11.

Like Adams and Davis, Reich ends on a spiritual note. He offers a somber recollection of volunteers who sat with the remains of the dead, keeping their souls company, waiting for sometimes days, weeks or months for a Jewish burial, condensed in the string quartet to five of the most heart-rending moments Reich has written.

That was followed by Samuel Barber’s Adagio, America’s go-to music of mourning, a cube of sugar we add to our bitter drink of mourning. This could have cheapened a very important concert. But the Lyris played not for sentiment but just for the notes on the page, take them or leave them, no emotional manipulation required. The Lyris’ first public performance in 18 months restored the ravishing, church- and soul-filling beauty for which this quartet, like Davis’ “Restless Mourning,” should be far better known.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.