It is hard to be bigger than the architecture of the Geffen Contemporary at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles. Once a warehouse for the LAPD’s automotive fleet, its dimensions are on the monumental side: 40,000 square feet of floor space with a ceiling height of 35 feet. And though Frank Gehry converted it into a museum in the early 1980s, inserting a sequence of moderately sized galleries into the cavernous space, the building nonetheless retains its industrial aspect. Surfaces are concrete and corrugated metal. And if you work at a less-than-ginormous scale, it can make your art seem as if it’s Victorian miniature.

Geffen Contemporary, meet Pipilotti Rist.

Our culture team breaks down all the shows, movies, stage productions, music and more to keep on your radar this fall.

The Swiss artist has not only taken over the building for her first West Coast survey, “Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor,” which goes on view Sept. 12, but she has also inhaled it whole, transforming its austere spaces with a sensory web of color, sound, light and video installation. The warehouse is now a sumptuous garden; its walls, its windows and its floors, a place onto which Rist projects videos, many of which meld body and landscape in a deeply saturated palette, and which are often accompanied by goopy, amniotic soundtracks.

“With projection, you open up the walls,” says Rist, gesturing at the building around us. “You make the architecture fluid.”

Walking into the Geffen now is less like entering a building than being engulfed by a primal world.

“In every place and in every way, we find outpouring,” says MOCA curator Anna Katz, who organized the show in collaboration with curatorial assistant Karlyn Olvido. As Southern California contends with “Pandemic 2.0: The Delta Variant,” Katz anticipates that Rist’s exhibition is “going to be a bit of a tonic.”

It certainly feels that way. Rist’s worlds are a brilliant ocean into which you’ll want to plunge and be carried away by its currents.

The pandemic has depleted us. Pipilotti Rist supercharges us with color and light.

Though long a recognizable name in the art world, Rist is perhaps best known in pop culture as having been a source of inspiration for Beyoncé’s 2016 music video for “Hold Up.”

In it, the pop star is seen happily smashing car windows with a baseball bat while decked out in a billowing yellow dress. The visuals resemble a 1997 work by Rist, “Ever Is Over All,” in which a woman — Swiss filmmaker Silvana Ceschi, a friend of the artist — is seen smashing car windows with a large metallic flower. Ceschi wears a sky-blue dress and shoes the color of red nail polish, and she smiles gleefully as she strolls down a Zurich side street, making rubble of passenger windows.

When Beyoncé’s video came out, some breathless critical takes likened the visual echo to intellectual theft, but Rist was flattered by the nod. “I’m not so interested in authorship per se,” says the artist.

But she is curious why the singer didn’t use the opportunity to smash more windshields. “I only did the side windows because I couldn’t afford to replace the front windows,” she says. “She could have done it!”

Rist emits a throaty laugh — one that conveys all the delights of merrily smashing up glass.

For our interview, Rist and I sit in a barren gallery at the Geffen that is being employed as a staging area for her show. At 59, she remains youthful, folding her sinewy frame into a semi-cross-legged position on a bench. The bench is blue. Her patterned tunic contains blue. And there is a streak in her hair that is also blue. It’s as if a bolt of color had reached down from the heavens to strike the spot she inhabits.

Rist is intrigued by the power of color and the effect it can have on the senses. In her videos, blues are crystalline, greens burst with fecundity and reds evoke the color of blood. Sometimes actual blood appears in her work, of the brilliant, freshly-bled sort.

Artist April Bey’s sumptuous solo show “Atlantica, The Gilda Region” at CAAM imagines a world in which “all Black people are loved and accepted.”

Last year, she told Calvin Tomkins of the New Yorker that, “In the Western world, color is underestimated.”

At MOCA on a break from installing her show, she expands on that statement. “There are different reasons why the snobbish West would not appreciate the colors,” she says in her Swiss-German accent. “One reason is that they think it’s too exotic, it’s too wild. ... One hundred years ago in Europe, probably also in America, the respectable person would be the teacher or the priest and they would wear dark [colors] and black and they’d say, ‘My true values are deep inside, I don’t need to show them.’”

Rist, however, is interested in the states that color elicits. “Color, like music, you cannot hold back from an emotion,” she says. “Whereas black and white is linked with writing and the letter and with reason, color is not rational, color is dangerous. You fall into it. You can’t control it.”

“It’s more linked to women and to children,” she adds. “There are so many ways to try to say that children and women don’t have to be taken seriously.”

And, certainly, it’d be a mistake not to take Rist seriously. Her art may bear vivid, ebullient surfaces, but the emotional states they evoke go deep. As Katz notes, “There is pleasure and pain.”

Pipilotti Rist was born Elisabeth Charlotte Rist in Grabs, Switzerland, the daughter of a doctor and a teacher. Pipilotti is a nickname inspired by Pippi Longstocking, the adventuresome Swedish children’s book character (and later, TV character) — and, indeed, there is a fierceness they share.

Rist became intrigued by experimental cinema in the early 1980s during her studies at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, and later took classes in video production at the School of Design in Basel, Switzerland. For a time, she tried her hand at performance. In the 1980s and ‘90s, she performed with a feminist-punk-klezmer-cabaret act called Les Reines Prochaines. (One of their more delightful videos opens with footage of a bright pink colon, though it could also be an esophagus — a harbinger of Rist’s later work, which dwells on the body.)

But it was video, not performance, that would ultimately be her métier. In the late 1980s, she began to draw the attention of experimental film groups and the art world with an eight-minute piece titled “I’m Not the Girl Who Misses Much.” The video features the artist, clad in a black dress, singing the title of the piece, a line inspired by the opening lyric from the Beatles song “Happiness is a Warm Gun.”

The Beatles version is languid; Rist’s is the opposite. She dances maniacally and plays the tape at high speed so that she sounds like a chipmunk. It’s funny, but with an edge — Rist, early on, toying with ideas of the uncontrollable.

She followed this up with other videos that took on the body in curious, deadpan ways: a naked man flapping about in a forest frolic, a visual riff on menstrual blood and a “porno” titled “Pickelporno,” from 1992, which wasn’t really a porno, but instead an abstracted meditation on sensation that imagined pornography that might appeal to women. (These are all in the MOCA show.)

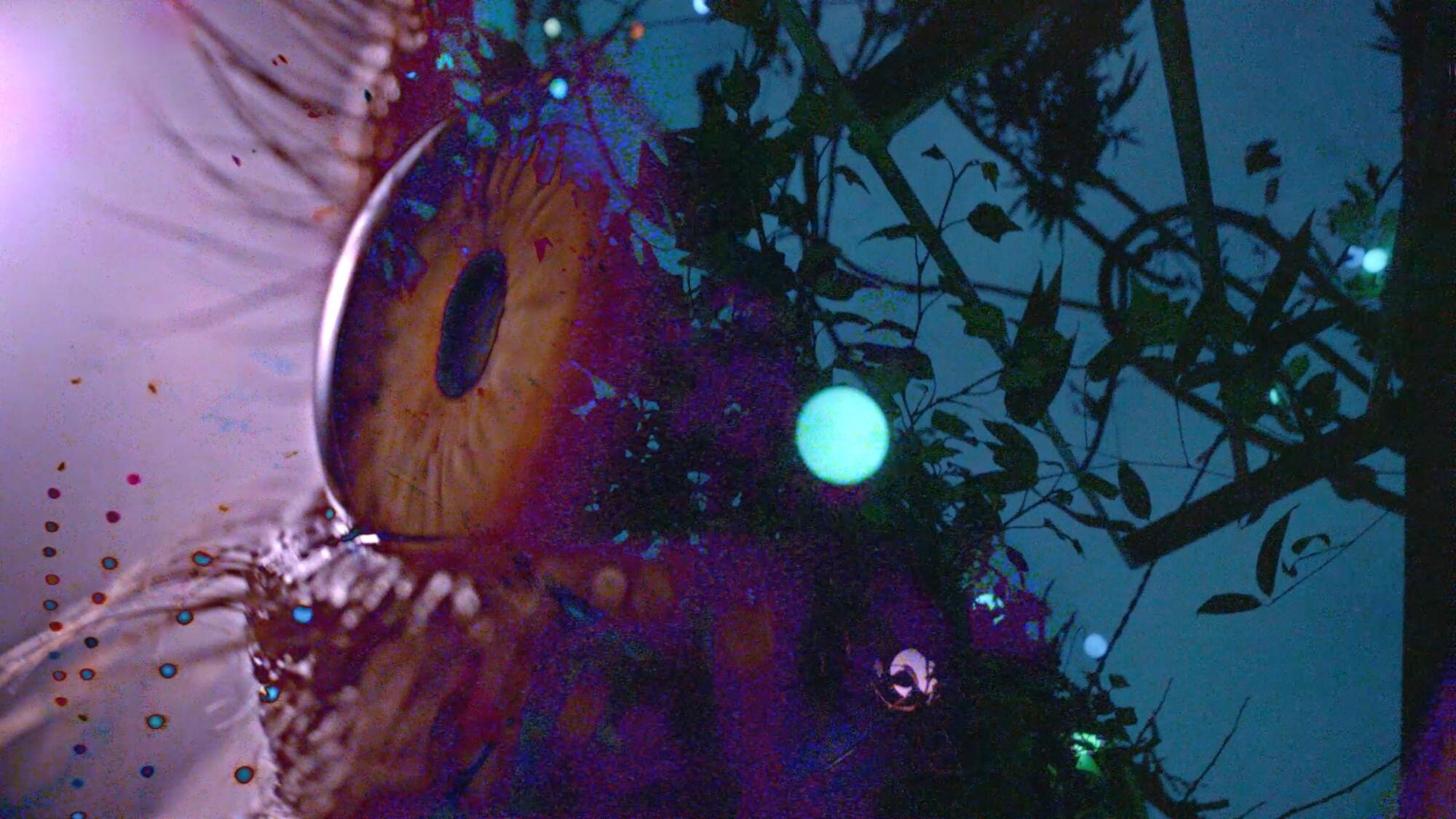

“Pickelporno” uses a style of filming that the artist retains to this day. Rist deploys tiny cameras in extreme close-ups, capturing minute details of skin and hair and bits of the human body — all the bits. It’s sensuous and lush and feels nothing like the clinical copulation you see in porn.

“It’s a constantly roving camera, and a close-up view,” says Katz. “It’s the opposite of the idea of video as surveillance or a passive gaze.”

You don’t watch Rist’s work so much as inhabit it.

That was certainly true by 1996 when the artist broke from the TV monitor and turned to projections.

The turnkey work was “Sip My Ocean,” a large-scale two-channel installation that featured kaleidoscopic footage of objects and bodies floating in a brilliant blue sea. The soundtrack, which features music by collaborator Anders Guggisberg, features Rist singing two versions of Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game” layered one over another. In one version she sings normally; in another, she shouts the lyrics in an exaggeratedly high pitch. “Sip My Ocean” is about love, but it doesn’t descend into cheesy romanticism. Instead, it’s all elation and vulnerability.

It also engages the viewer physically. The seating found in video installations in museums is frequently so terrible that it can make watching video feel like penance. Rist, however, offers viewers of “Sip My Ocean” a deep pile rug and large cushions on which they can lie back and let the watery visuals wash over them.

“Thinking about the difference of watching a video at home or watching television and then going to a museum, it occurred to me that people bring their physical presence there,” she explains. “I want to pay attention and give respect to that.”

This has turned her installations into informal happenings.

In 2008, Rist took over the mammoth atrium at New York’s Museum of Modern Art with her installation, “Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters).” The work consisted of 25-foot high projections of bodies and flowers and fertile gardens. Viewers sat in and around a sculptural installation that took the form of a human eye. She also supplied dozens of rather labial pink pillows.

I saw the piece at MoMA and was enthralled. The video is only 16 minutes long, yet I spent a good hour lying in place, overwhelmed by my worm’s-eye view of Rist’s natural world — which included footage of a charismatic pig and a giant pink breast.

The video, combined with the architecture of the seating, transformed the room into a convivial gathering space. The New York Times’ Karen Rosenberg described it as the first project “to humanize and feminize the atrium.”

Rist takes the immersive experience to another level in her MOCA show, which will represent the rare opportunity to see a large number of her pieces in Southern California. (It’s not the artist’s first time hanging out in L.A.: In the early ‘90s, she taught at UCLA for a year.)

At the Geffen, she has rendered the interiors unrecognizable. Around the perimeter of the galleries, she has obscured the Geffen’s industrial architecture with the facades of cozy houses. These harbor hallucinatory, “Alice in Wonderland”-style spaces that literally put the viewer in the work. A den features a massive couch where you can clamber up, like a child, and watch the artist’s early work on a television set. Inside a trippy lounge, an easy chair offers a place for relaxation — and a place where videos of earthy visions can play out on your groin.

At the center of the museum, Rist has created a space that evokes a fantastical garden. Strands of LED lights create a forest of organic shapes that throb with shifting colors and tones. (Rist is as interested in the physiological effects of light as she is in color.)

Elsewhere, projections of vegetation come to life on the walls. In these, as in other works, human bodies seamlessly merge into landscape. Is that an underwater rock formation? Or a human testicle? Does it matter? In Rist’s world, the human is always a part of nature — never apart from it.

“I’m looking for archetypic, common, collective images,” she says. “And landscape is one of the foundations where we can meet.”

The show is an overdose. (Which is probably why MOCA will allow visitors to make a second visit on a single special admission ticket.) But it’s a welcome overdose.

The pandemic has depleted us. Rist supercharges us with color and light.

“It’s like, what a gift,” she says of being in possession of a human body. “It’s heavy to live, but it’s also such an incredible gift.”

The show was delayed for more than a year because of the coronavirus pandemic. But the timing, it turns out, is just right. Rist’s work is about the poetry of being fully, magically, blazingly alive. And right now, we could all use some of that.

Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor

Where: The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, 152 N. Central Ave., downtown Los Angeles

When: Opens Sept. 12 and runs through June 6, 2022

Admission: $18/$10 for adults/students; advance timed-entry tickets are required

Info: moca.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.