Review: If you’re missing Dudamel at the Bowl this summer, you’re missing greatness

May I make a modest proposal for the Hollywood Bowl? How about commissioning a Los Angeles artist to create some sort of tribute to a bag of Cheetos?

It was that salty, greasy, cheesy snack 16 summers ago that proved a true marker for the remarkable concerts that have been taking place in the amphitheater this summer. Back then, the picnickers in a box near me put down the Cheetos and forgot about the bag as they listened to a curly-headed young conductor no one knew.

That concert ended with Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony played with remarkable gusto. The head that conducted it is now turning gray, and Tuesday night he returned to the symphony at the Bowl with his Los Angeles Philharmonic, as he will once again Thursday. Gustavo Dudamel’s Tchaikovsky has inevitably deepened and matured. The performance was on a level that only three other (and all older) current music directors might, for my money, achieve in Tchaikovsky’s Fifth with their enviable orchestras: Kirill Petrenko and his Berlin Philharmonic, Valery Gergiev and his Mariinsky Orchestra and Semyon Bychkov and his Czech Philharmonic.

But Dudamel did this at the Bowl.

The Bowl is different this summer from ever before, the obvious reason being the pandemic. When the L.A. Phil season began in July, we were overjoyed to have an orchestra playing together the way an orchestra could. We were overjoyed to throw off our masks, picnic and gather. There was a sense of triumph. But there were also new feelings of purpose. Music mattered. The Bowl wasn’t just about partying.

There was more. A tweaked sound system now conveys, in the genuine and gloriously immersive way that truly great audio can, actual musical sensation and substance. There seems to be a shared sense that we are all in something momentous, in our times, together.

Yo-Yo Ma reprises his Bach marathon, the Ojai festival returns at long last and San Diego gathers at the new Rady Shell. Let the season begin.

People came to picnic once more, and that is a Bowl pleasure not to be denied. But over the years, it became the main purpose for too many. The orchestra was background. If truth be told, many musicians and many music lovers came to find the Bowl distasteful.

We’re back to masks at the Bowl, except when actively eating or drinking (although a little effort is yet needed to gently get compliance). We still are able to enjoy a picnic. But we’ve found the balance. I can’t say for sure that somewhere in the big Bowl, there wasn’t someone clumsily chomping Cheetos on Tuesday as the horn played Tchaikovsky’s famed sorrowful solo in the second movement with the buttery silkiness of the best French pastries. But I can’t imagine it. My predecessor, Martin Bernheimer, liked to document clanking wine bottles rolling down aisles at every Bowl concert. I haven’t noticed one all summer.

What there were, however, were people clapping between movements of the symphony, and at one point in the first movement at a sudden fortissimo. There was downright cheering after the first movement of Arturo Márquez’s Violin Concerto, which had its premiere in the first half of the concert. That is exactly the proof that the Bowl now matters as it has not for decades.

The haughty old taboo against clapping between movements is long gone. These days clapping whenever is more often than not welcomed as a sign of essential new audiences. When enthusiastic new audiences are listening as intently as everyone else, there is hope for the future of an evolving art form.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

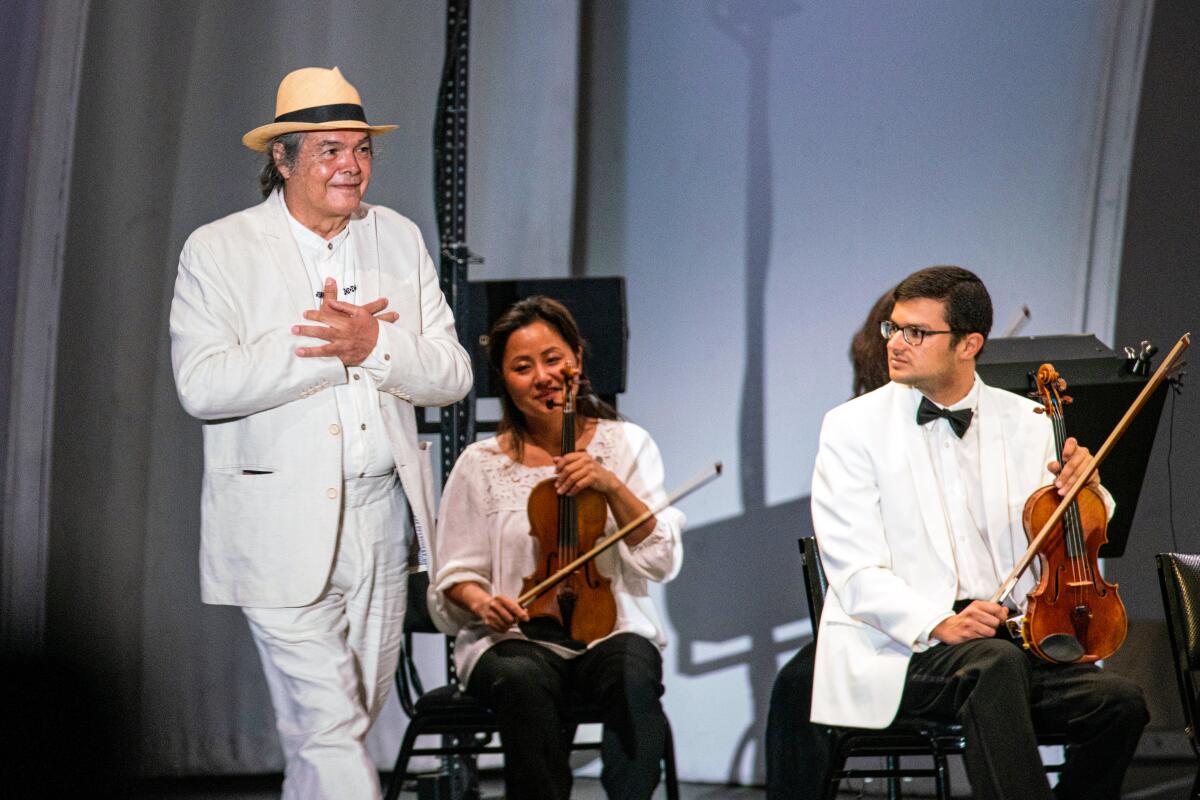

Márquez’s new concerto, “Fandango,” commissioned by the L.A. Phil and written for violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, is substantial. It is based on the Mexican fandango Márquez grew up with in Sonora. His instrument is the violin, and his father was a mariachi violinist. But Márquez’s goal in the concerto was to use his folk and dance roots in a formal classical way, taking as his example such European composers as Manuel de Falla and Isaac Albéniz.

The result is a perhaps overly conventional concerto that adapts rather than transforms. Márquez is not a Villa-Lobos, with whose Prelude to “Bachianas Brasileiras” No. 4, Bach Brazilian-ized, Dudamel rapturously opened the program. But Márquez has the elusive popular touch that has made his Danzón No. 2 a hit and a special favorite of Dudamel’s YOLA.

In Márquez’s concerto, he allows Meyers to revel in her virtuosity. He writes melodies that sound old and worth keeping. Dance rhythms do what they’re supposed to, making feet tap and nerves tingle. The orchestra is well used. If the score lacks originality, it never, in its nearly 35 minutes, lets the listener down. That may well translate into a dance-driven concerto having legs.

When Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony was new, it seemed to the sophisticates to have far less going for it than does Márquez’s concerto. Like Beethoven’s Fifth, it has a fate motive and like that Fifth of all Fifths, it ends in triumph over adversity. Except the triumph here is bombast, which can be a dangerous thing.

Sixteen years ago, Dudamel made a meal of all it — the good, the bad, the inconsequential. He was young. He was brilliant. He made it living, breathing music. He has since turned repeatedly to Tchaikovsky, and the Fifth remained living, breathing music for him Tuesday, but not on the individual level.

Exhibiting patience over pathos, grandeur over ephemeral urgency, Dudamel now achieves a grand sweep. He is hardly above treating a climax like a ball to be hit out of the park (hence the first movement cheering section), but everything is put in context. He lets Tchaikovsky have his tears and triumph, but within Chekhov-ian bounds. What is, is, and we must learn to let it be. A dead seagull is a sad sight, but we must take it for no more or no less than that.

There were such moments after moments in this beautifully played, elegant yet exciting performance. The waltzes in the third movement felt not like Viennese at a ball but Russians skating on a frozen lake. The angst of the first movement was neither reined in nor unleashed, just life doing what it does to us all. The swagger-fed, feel-good Finale sounded good on the surface without necessarily being, in the best Russian manner, more than superficially convincing. Each tomorrow, Chekhov was expert at reminding us, has something up its sleeve — just like the many unknowns that face each passing night at the Bowl, which now included the possibility of Cheetos-proof greatness.

COVID-19 disruptions in shipping have stranded a European opera set at sea, so LAO will build another. Three months of work are crammed into 10 days.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.