Review: In rollout of Dudamel Fellows at the Hollywood Bowl, Tianyi Lu impresses

This is not a normal Hollywood Bowl summer.

No, I am not referring to our convoluted attempts to extricate ourselves from the pandemic. Attending the Bowl is, thus far, surprisingly as it has always been. All are welcome. The weather is fine. With restrictions removed, the simple pleasures of carefree outdoor concertgoing we had stopped taking for granted are newly granted — no matter, for the moment, the sudden COVID-19 surge in L.A. County.

For the record:

3:12 p.m. July 25, 2021A previous version of this story misspelled a conductor’s name as Taniya Lu. She is Tianyi Lu.

What is strikingly different this summer concerns the bread-and-butter weekday Los Angeles Philharmonic concerts. One predicted consequence of the pandemic has been that the arts would necessarily become more local. For reasons economic and environmental, “travel” is an increasingly dirty word.

In the case of the Bowl, we have an L.A. Phil summer that is all about Gustavo Dudamel and his orchestra. The music director, himself, conducts an unprecedented five weeks. The other conductors include six former Dudamel Fellows, the program in which young conductors are chosen to work as assistants.

Five of those fellows are emerging young conductors making their Bowl debuts, the first two of which were on Tuesday and Thursday evenings. Each may be a discovery, given the exceptional success of the program. Among former fellows who got notable big breaks here are the two most exciting young conductors on the scene — the already superstar Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla and Rafael Payare, music director of the San Diego Symphony, who will open that orchestra’s futuristic Rady Shell on Aug. 6 and who has just been appointed music director of the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal.

There are many advantages to this localism (even if “localism” might mean air miles for conductors and soloists). A Bowl debut is a trial by fire for a young conductor. Rehearsal is typically the morning of the concert, with barely time to run through the program. That’s not for everyone. Among the notable failures is Kirill Petrenko. In 2002, the now celebrated music director of the Berlin Philharmonic was a monastically probing and intense young Russian fish out of water who made little impression.

The advantage the Dudamel Fellows enjoy is that they know the ropes. They have served as cover conductors at the Bowl, ready to step in at the last minute if necessary. An added attraction is that the Dudamel Fellows have always been admirably diverse. By keeping it in the family, everyone on the Bowl podium Tuesday and Thursday nights this year happens to be a woman and/or conductor of color.

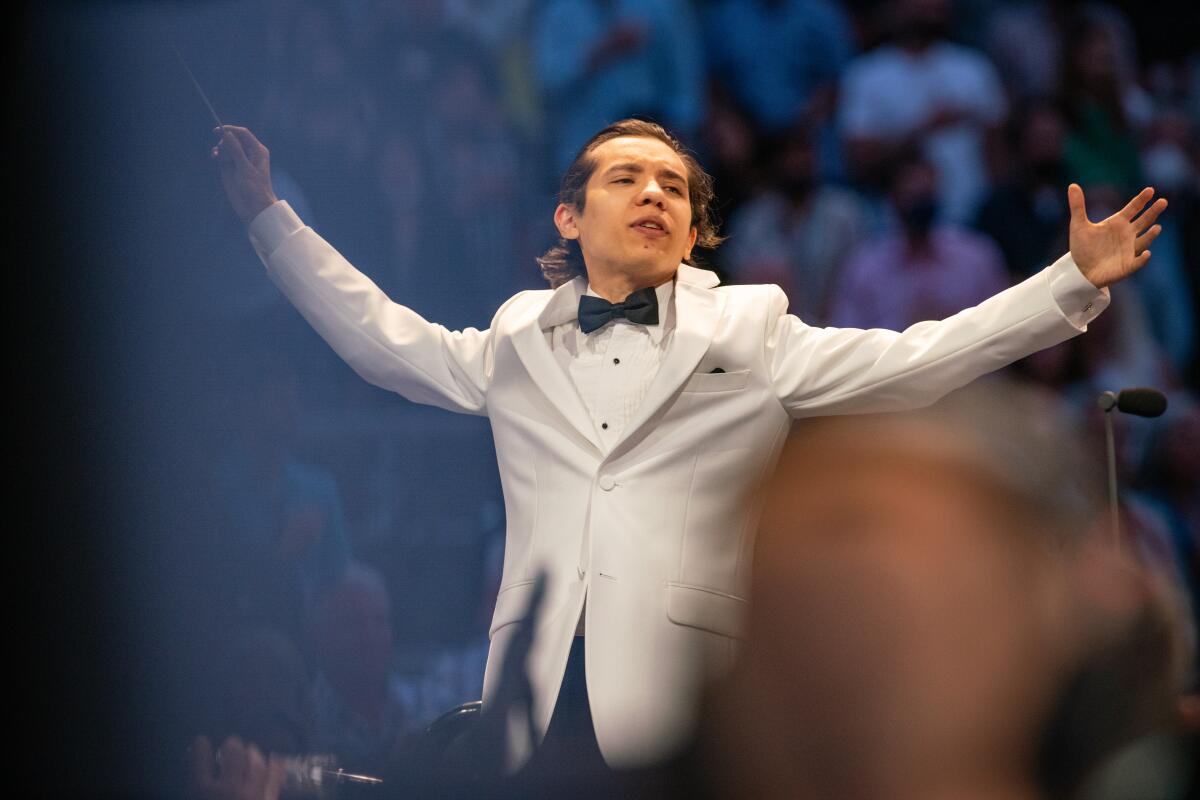

Even so, a Bowl debut remains a nail-biter. Both Tuesday and Thursday were exceptional, but in opposite ways. First up was Tianyi Lu of Shanghai, a Dudamel Fellow during the 2017-18 season. She took first place in the Sir Georg Solti Conducting Competition in Frankfurt last year, and her guest conducting invitations are understandably pilling up.

She is slight, with slender long arms that trace phrases in stately elegant arcs almost like branches of a tree in a wind. Her facial expressions are those of wonder at each orchestral effect. She knows what she wants; she knows how to make a listener (and seemingly an orchestra) want what she wants; and she knows how to get it.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

She didn’t make it easy on herself. She began her program with two premieres. The first performance of Ricardo Molla’s “Fanfare for a New Beginning,” which had touches of Hollywood, proved pleasant but inconsequential. The U.S. premiere of Thea Musgrave’s Trumpet Concerto, on the other hand, was consequential and a delight.

Written for Alison Balsom as soloist and an L.A. Phil co-commission with Grazinyte-Tyla’s City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (keeping it all the more in the family), the score was inspired by an exhibition of Victoria Crowe tree paintings Musgrave saw in 2018 when she was being honored at the Edinburgh Festival on the occasion of her 90th birthday. The bare twig-lean branches of Crowe’s trees can take on the appearance of roots in their representation of interconnectedness.

Musgrave’s other inspiration is the singing tone of Balsom’s trumpet, like none I’ve ever heard on the instrument. Five short movements referred to five paintings, atmospheric of the seasons, whether snowy white or white nights.

Trees, we are fast learning, communicate with themselves and their surroundings in profoundly remarkable ways that determine essential aspects of the eco-structure of forests and the life of the planet. Whether or not that was Musgrave’s purpose, she operated similarly with a concerto of communication in which the trumpet had various lively dialogues with orchestra soloists — a clarinetist waves to the crowd; a cellist enters into a lyrical tete-á-tete with the trumpet solo; an orchestra trumpet serves as a kind of echo chamber to Balsom.

Musgrave’s orchestral writing is robust. Her melodies don’t go where you expect them to but sound like they’re meant to be the way they are. We don’t understand trees. We hunt them and we hug them. Musgrave, who appeared a sprightly 93 as she waved from her box at the curtain call, composes to this mystery with rare grace.

Lu concluded the pictures theme with a sprightly “Pictures at an Exhibition,” using the familiar Ravel orchestration of Mussorgsky’s piano score. She also continued the graceful lean branches blowing in the wind manner by making every amazing Ravel effect sound clear, clean and carefully etched. She refrained from the lushness and theater Dudamel brings to “Pictures.” Her way is short on pomp in her exquisite calligraphic musical pictorialism.

I’ll keep it short for Enluis Montes Olivar. I had seen the young Venezuelan conductor work with YOLA two years ago and was taken with his exuberant spirit. Thursday night, his exuberance misfired.

He opened with a curiosity, “Santa Cruz de Pacairigua,” written in 1954 by Evencio Castellanos, who had been mentor of José Antonio Abreu, the founder of El Sistema. Venezuelan dance music somehow didn’t dance.

Olivar was saddled with the debut of young Czech pianist Lukás Vondrácek, who banged through Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto as if he had brass knuckles on his fingers. By the time Olivar reached Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony, the orchestra played like it had had enough. Determined but imprecise, Olivar seemed stuck in the mode of stirring everything up. Too much stirring makes a mess.

It was a tough night for Olivar, who may now understand that pomp has its limits. Whipping up excitement with YOLA isn’t the same as with the L.A. Phil. The remaining three Dudamel Fellow debutants — Ruth Reinhardt, Gemma New and Marta Gardolinska — are somewhat more experienced. But there can never be anything approaching normal for a young conductor standing on the Bowl stage for the first time.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.