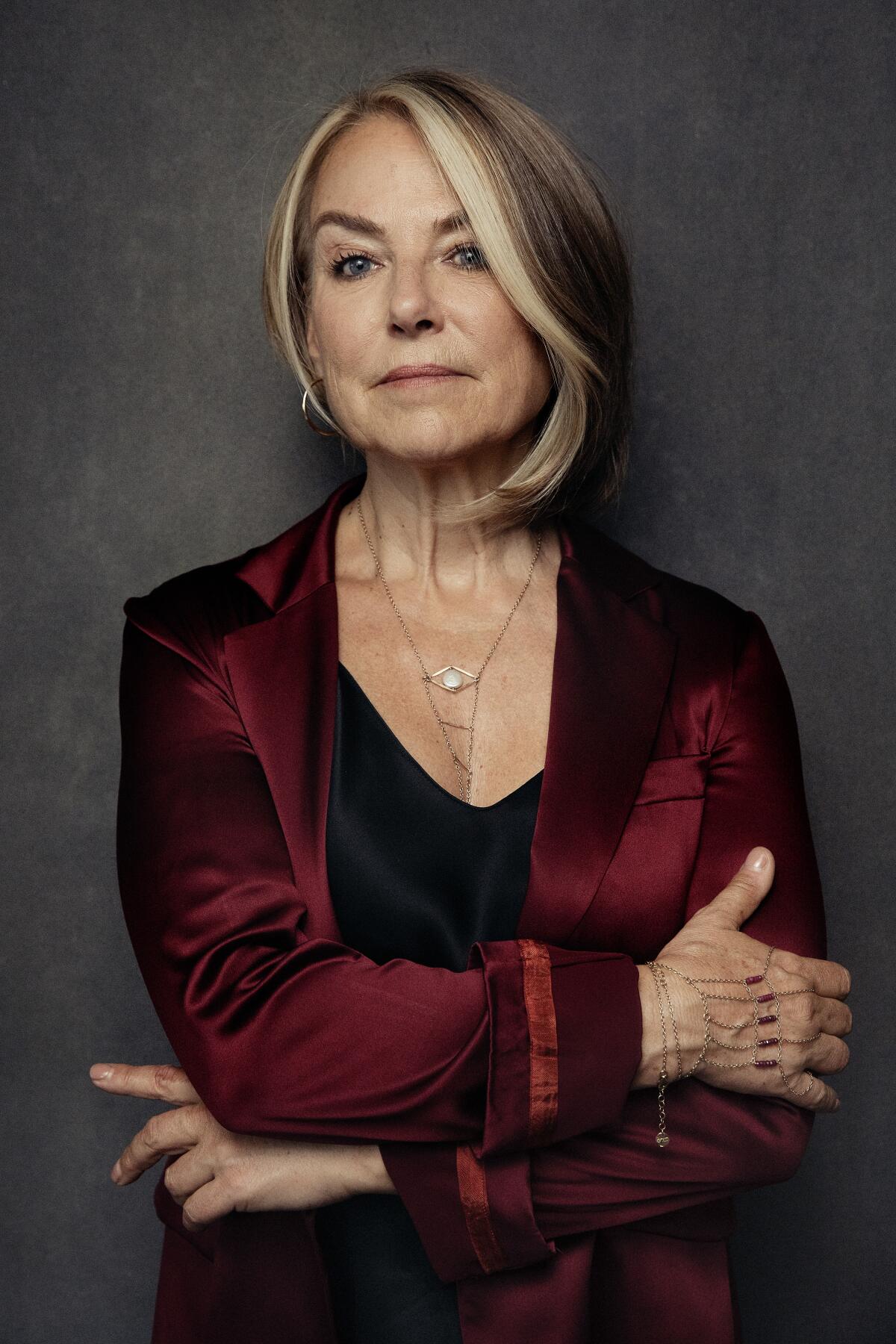

Games are therapy. Don’t believe us? Ask famed relationship therapist Esther Perel

A game, says Esther Perel, the famed psychotherapist behind the relationship therapy podcast “Where Should We Begin?,” is a ritual.

Sometimes, in therapy sessions, Perel will toss patients a ball, initiating a game of catch in which one can only speak when holding the toy, turning potentially challenging talks into a game of inclusion. Other times, she instructs couples who can’t stop fighting to lie on the floor, seeking to disarm them of any active posturing.

This, to Perel, is play. It’s an attempt to create an imaginary structure with game-like rules. Or, to “create a ritual,” says the author of multiple relationship books and a sometimes puppeteer, who is now also a game developer. Her newly released “Where Should We Begin? — A Game of Stories” takes its name from her podcast and comes in a box designed, she says, to look like it might house exquisite Belgian chocolates.

During a recent virtual call with Perel, who was at her home in New York, we open the box and instead of chocolates, I find a set of cards meant to inspire participants to tell a story. Soon I am playing a game in which I find myself revealing inner secrets with one of the most accomplished therapists of our time.

Following the path Perel suggests, the cards lead me to talk about something I wouldn’t tell my parents, as well as a habit I need to let go. A tale of selfishness, loneliness and insecurity emerges from my recent pandemic-era past, along with a mistake that gets me to think more deeply about games as a therapeutic tool.

I’m trying to figure out if Perel is joking — or speaking in metaphors — when her advice involves a match, a piece of paper and an invitation to a friend, a companion or a date to more or less burn the past and set expectations aflame by creating a ritual of play. More on that later. For now, I ask her to spell out for readers what the word “ritual” means to her.

“A ritual encapsulates a whole story,” Perel says. “Light a candle. Behind that candle is a whole story of commemoration, celebration, welcoming or yearning. But the candle doesn’t tell it just by its flame. By the context it’s all explained. Stories are like play, as play makes the stories.”

Think of each card in “Where Should We Begin?” as that candle, a story waiting to unfold based on who is playing it and in what setting.

‘Play is fundamental’

For those in therapy, it makes sense that Perel would make a game.

Therapy can and even sometimes should feel like a game. For when we play, we are present. But more importantly, we are malleable, dropping preconceived notions of what should or shouldn’t happen. We’re also more accepting of change and open to learning and addressing negative habits. And therapy is an opportunity, of course, to role play.

Play, says Perel, “is the way we make sense of our lives.”

“Play is fundamental,” she continues. “It is a key to our hierarchy of needs. You see that with child development. But because it is fundamental with children we have mistaken it. We say, ‘Play is for children.’ In fact, it performs an essential role in society. We know that play is, by definition, associated with our psychological, emotional and social well-being.”

It’s safe to say that none of us, including myself, a journalist who writes about games for a living, play enough.

For all the struggles many of us endured during the pandemic — the uncertainty, the loss, the loneliness, the isolation and the emotional havoc wreaked by all of it combined — a positive of the last year and a half was that we were reminded of the power of play.

Happy hours over video conferencing apps quickly become tiresome, yet games such as “Animal Crossing: New Horizons,” “Among Us,” “Minecraft” and others thrived not because we were starved for entertainment but because they provided a means to communicate, an essential lesson we can apply to our daily life as we put down the screens. But this story isn’t about video games, which themselves can be high-priced items for the privileged, but more about the act of play, which is for everyone.

“I think that a bunch of people found video games during the pandemic,” says behavioral scientist Jon Levy, whose recent book “You’re Invited” circles back to the importance of play numerous times when it comes to connecting with others. “Like getting a bunch of people together and playing ‘Among Us,’ that’s awesome.”

Yet that’s not so much what Levy is interested in.

“I think the remedy, as we come out of this pandemic, is to not confuse play and party,” he says. “I think a lot of people will go out and start socializing and start drinking and get hangovers and all that, but what we want is play. What we want is that feeling of freedom in social interaction. I think the cure for loneliness and isolation is play. It’s low stakes. It’s high reward and it triggers belonging.”

Well, then, how do we play? And what and where?

Anything and anywhere, of course, but that’s easier said than done, and comes down to individual tastes and personal tolerance. Plus, our culture has hang-ups.

“In a Protestant, puritan, antihedonistic and work-driven culture, play is not seen as productive,” says Perel. “It’s seen as not having an outcome. I think Protestant societies are challenged, because it is not something you can measure.”

Game designer-author Holly Gramazio says many view play as “hokey or embarrassing.” She recently collaborated on the book “The Infinite Playground,” a celebration of imagination in daily life and one full of play ideas that ask us to look at our world as a game board. The next time you’re in a museum, for instance, ask yourself: What one painting or sculpture would you take home if given the opportunity?

While not a game, per se, it is play.

Gramazio has worked on a card game, “Art Deck,” designed to get us to draw unexpectedly — a fast-track into learning the brains of our drawing companions — and has a passion for installation-like games that take place in public spaces.

“I’m interested in playing in a space as a way of knowing that space and feeling at home there,” says Gramazio. “When you were little, there was probably a game that depended on the specific details of the space — a staircase or a corner — and a game that took advantage of those details. I think play that takes advantage of the details of a space can make us feel at home there. I like giving people those experiences.”

Like the principles that drive the work of Santa Fe, N.M., art collective Meow Wolf, whose walk-through experiences in Santa Fe and Las Vegas turn the mundane — a suburban house, a grocery store — into the fantastical, Gramazio’s games, as well as Perel’s personal card game, are all reminders that our own imagination has the ability to do the same with regularity.

Should daily life be gamified?

Perhaps, before we go further, we should briefly discuss escapism. Or high scores. Or leveling up. The language we have to talk about play isn’t always useful. It can trivialize something that should be ingrained in daily life.

But escapism is not some low-brow video game or superhero movie. No, what is real are the stories we tell ourselves, and they can be animated, interactive or housed in a museum. Escapism is art, and art of the highest order. Too often we confuse the words real and serious, underselling the need and the prevalence of escapism.

“It is daily life, with its messy details, and frustrating lack of definition and completion — its many inconclusive moves and projects twisting and turning as in a fitful dream — that is unreal,” writes Yi-Fu Tuan, a geographer who studies our philosophical relation to our spaces in his book “Escapism.”

“Real,” writes Tuan, “by contrast, is the well-told story.”

“Where Should We Begin?” joins a cadre of games in the how-to-better-communicate genre. Though there are instructions included for a “safe for work” version of Perel’s game, it’s geared toward players who are intimate with each other, be it dear friends or partners. It will sit happily on my shelf next to some of my favorites in the field, including Aubrey Lynn Isaacman’s “Intimacy,” a game about navigating consent, and Naomi Clark’s “Consentacle,” a work that explores nonverbal communication with a sci-fi backdrop.

There’s also a broader field of study around the gamification of daily life. This can range from point systems for chores or dieting to worksheets that view personal challenges as “bad guys,” or workplaces such as Amazon that are reported to use games to increase productivity. This sort of thinking, while I don’t doubt can be beneficial to many, generally hasn’t worked for me.

Gramazio helped me articulate the reason why. “I am really opposed to mandatory play,” she says. “Like, if you have to play a game, it’s no longer a game.” She cites an example of trying to apply game principles to her to-do lists, of utilizing different highlighters and colors of paper to create order and accomplishment, which works, briefly, until her brain gets tired of the rules.

I’m more interested in maintaining a playful, curiosity-driven way of thought than adding gamification techniques to my day.

“If you really want to take your happiness and success and career and family more seriously,” Levy says, “the key might be to take them less seriously. Fundamentally, we’re lonelier than we’ve ever been, and the health effects of that are dramatic. But people do connect really well when they have a joint activity. A game that is simple takes the pressure right off.”

I thought of this comment while thinking of the most important game I played during these late pandemic days, which incorporated an accompanying app but was centered on something I always thought was impossible for my racing mind: meditation.

It turns out a lot of other people think they’re bad at meditation too, which led to the creation of the Muse headband. “I’m a psychotherapist who teaches my patients to meditate, but I hated meditation,” says Ariel Garten, one of the core three developers of the Muse, designed to monitor brain activity and provide light audio prompts — a bird chirping, thunder — to put an aural image to how the brain is working (or, you know, during the pandemic, how the brain is not working all that well).

“A million people can tell you what you’re supposed to do during meditation, but then the moment comes when you’re alone in a room with your thoughts that you’re trying to escape and they don’t go away,” Garten says. “So you think you’re not good at it, and we do not like doing things we’re not good at.”

With Muse strapped around my head, some could argue I wasn’t meditating so much as hearing imagined forest worlds. But it worked, putting me in a game-like focus. I became a protagonist on an excavation into my brain.

When I was able to shift my mind away to the thoughts I was trying to avoid, I would hear birds. But if I went back to a more depressing space, the rain came. What struck me with Muse, though, was that you can’t “win” at it, that is if you get excited that you’re hearing more birds, you have increased brain activity and the birds fly away.

Talking to Garten about what Muse is trying to teach through play hit hard. I‘ve strained personal relationships over the past year and a half, even viewing some as life rafts, which placed undue pressure on them and didn’t allow me to keep perspective — or better get to know people I genuinely and deeply care about. Keeping expectations in check is one of Muse’s goals.

“Even though we’re giving you reinforcement with the birds, you’re learning that you need to be equally as uninvested in your rewards and your failures,” says Garten. “It’s a lesson in equanimity. It’s a fascinating balance. We get you hooked, and you care about how many birds you get, but you need to be uninvested in getting the birds.”

Because? “That bird flies away,” she says.

“Through play, we create our opportunity, and we get out of our fixed space,” says Garten. “So much of our neuroses or problems are because we get rigidly fixed on ideas. Psychological flexibility is the greatest predictor of success in a relationship. When we’re able to be psychologically flexible — play — we move from a rigid space to one that can explore the possibilities that aren’t necessarily directly in front of us. So yes, play is essential.”

An antidote to heaviness

That’s why, of course, it’s long been a common thread throughout Perel’s work. She recently wrote an essay on the connections between play and human intimacy, a core of her interests throughout her career. “Just like sex, playing as adults is about pleasure, connection, creativity, fantasy — all the juicy parts of life we savor,” Perel wrote.

And during the pandemic, Perel started to think of play as something we would require more than ever as we not only get reacquainted with the world but with each other. While there is a sense in Southern California of returning to normalcy, there are long-term emotional effects of the pandemic that are likely to stay with us.

Front of mind still for Perel are issues concerning “collective grief, prolonged uncertainty, ambiguous loss and stress,” all of which may rear their heads at unexpected moments. She lists them and says, “This is heavy.”

And thus, she says, she started thinking of a game, but she doesn’t use that term: She talks of something prescriptive.

“What is the antidote to that heaviness, to that vigilance to constant risk management that we’re dealing with?” she says. “I wanted to talk about the importance of maintaining a sense of humor, a sense of playfulness, of remaining curious and remaining connected to life and nature through art and play. I wanted to create an experience.”

The goal: a game about the stories we tell, don’t tell, half tell and why. Prompts throughout the game can be revealing — talk about a fantasy you’re conflicted about, or discuss a text you fantasize sending but won’t. What makes the game unique is the way in which those story prompts are paired with topics, which can alter the flow or tone of the narrative of the game.

Topics range from discussing awkwardness, humor or something cringe-inducing, which can lessen the weight for someone uncomfortable with instantly being vulnerable. Tokens can be used to direct conversations to or from a certain choice.

This format, the pairing of a prompt and a story card, ensures that the game can be replayed with little chance that a story would be repeated. It is also important to give players the freedom to not feel pressured to share something they may consider uncomfortable, especially in a larger group game or on a first date. Multiple cards can be revealed at once to mix and match, and there’s element of choice in the direction the storyteller aims to go.

“If I got a prompt card that said, ‘Share something that I’d never tell my mother,’ and then I got another prompt card that said, ‘Share something from my teenage point of view,’ that completely changes the way that I might interpret the story card, which says, ‘I’ll never forget about the time that ... ,’” says Steve Tam, who helped Perel develop the game. “If I’m thinking about it through the lens of something I wouldn’t tell my mother, my mind goes to maybe some more illicit memories. If I’m thinking about that card through the lens with my teenage point of view, I’m now going to a more nostalgic place.”

And still, the hope is that within the circle of play, vulnerability comes easier. Perel knew she had something when she play-tested the game with some of her oldest friends and heard secrets she didn’t know her lifelong confidants had.

“I don’t want people to play against each other,” she says. “I want a game where the presence of the group unlocks stuff in people that they didn’t see coming. It doesn’t have to happen in a therapy office. It happens at my dinner table.”

And it happens on a Zoom call. Once Perel and I start moving through her game, things escalate quickly. We talk first about sweets and vices. But it’s also hard to escape the recent pandemic, especially for those of us who went through challenging times and are eager to excavate them.

I should note, all this talk about play had me feeling relatively confident. Aside from moments of severe depression, I like to play all the time, and I’ve counted on games to rescue me from the former.

Yet if every psychotherapist I talk to tells me play is a key to happiness and growth, why, recently, did I recede, and stumble into habits I thought I had long since kicked? Sure, the pandemic, but I want — need — to get deeper — it’s too easy to blame a vice or an external event. Those are surface-level excuses, and then we don’t move forward with new tools. Bad things, after all, will always happen, but if play is a way to stop from spiraling, why did it recently fail me?

Or maybe it didn’t, since play is what set me on this journey of self-discovery. Perel’s cards create a veil in which digging into emotional struggles feels safe— a game for sharing and exhaling. We get to talking that a potential concern that’s crystallized recently isn’t that I can’t play — I love to play — but that when it comes to my imagination I try to script it.

That is, I build worlds and scenarios for professional and personal relationships, and often sketch out such imagined ideas on the page. I basically create a short, happily-ever-after story for every aspect of my life. When reality clashes with that fantasy, I can — let’s just say, stumble.

In the context of the game, she doesn’t say this as a major problem — whew — but I am encouraged to embrace my scripting habit and share it with those who are important to me, then play with it so it’s out in the open — toy with so it isn’t so much a below-the-surface anxiety as it is something to laugh over. Being that upfront that early is, well, more of an “oh dear” than a whew, but change isn’t stubborn; like being in a state of play, it comes from being vulnerable.

Perel offers me a sort of game prescription: an entry or, depending on the circumstance, reentry ritual.

Write down all my ideas and preconceived notions, she tells me, and then bring them along on a future get-together with someone important. “Everyone has preconceived notions,” Perel says. “So, take your little script and burn it in front of her, or drown it in water. Ask her to join with her own. Then you’ve created a play ritual. And then you can talk.”

I like that idea. It feels like casting a spell, but I was wondering if a match was too intense. Perel picks up on my thoughts and dismisses them with a smile: “The elements just make it more dramatic,” she says, clearly having fun with the conversation her cards inspired. But more important, we’re getting outside of ourselves, and creating a sense of escapism in the everyday — a moment of personal disarmament for later contemplation. This is ultimately a reason we play, and what a deck of “Where Should We Begin?” can facilitate.

It’s a game, after all, about getting real with ourselves and those we treasure, and that is its own form of escapism.

“Lift yourself beyond the mundane,” she says. “Transcend boundaries. Transcend the limits of reality. All of that is escapism. This is not a game where you forget yourself.”

No. After all, the best games aren’t the ones in which we slay a dragon. Unless, maybe, it’s a mental dragon.

The charming and therapeutic “Cozy Grove,” inspired by “Animal Crossing,” is just one recent release in the “wholesome games” movement. Why the games resonate.

“Black Mirror” fans may want to play “Eliza,” a game about technology, mental health and the perils of automated therapy and intimacy.

It turns out games are uniquely tailored to explore love, romance and heartbreak. Consider “Maquette,” “Genesis Noir” and “Journey of the Broken Circle,” interactive conversations that ask players to think about love.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.