Dodgers announcer Jaime Jarrín: Chicano Moratorium eyewitness

Before he was honored by the baseball Hall of Fame, before he earned national recognition as the translator for a teenage Fernando Valenzuela, even before he directed the Spanish-language radio coverage and production of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, Jaime Jarrín always considered himself a humble street reporter first.

“I was a newsman,” said Jarrín, 84, the Dodgers’ Spanish-language radio voice for more than six decades. “That was my foundation.”

That’s also what led him to Whittier Boulevard on the last Saturday morning of August 1970. The Dodgers were playing at home that night, but Jarrín, whose main job was as news director for KWKW-AM, didn’t want to miss what he knew would become the defining story of a generation.

The anger and frustration that gave birth to the National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War had been building for two years, and on this day, Aug. 29, it drew more than 20,000 people to the streets of East Los Angeles for what began as a peaceful march.

“I saw the anger among the people,” he remembered from his home in San Marino. “They were protesting the war. They were protesting the draft. They believed that the government was trying to [prevent] Chicano youth to go into universities.”

And Jarrín believed he had to be there to document it. La Opinion, the main Spanish-language newspaper in Los Angeles, had fewer than than 3,000 regular subscribers then, and KMEX, the city’s only Spanish-language TV station, was on a UHF channel that required a special antenna to watch.

That left radio as the main source of news in the Latino community, which was then mostly Mexican American, and KWKW had one of the largest audiences.

“It was my duty to be involved in all the affairs of the mejicano community,” Jarrín said.

He was so involved, so trusted, that the highjacker of a Frontier Airlines flight told authorities he would negotiate only with Jarrín, who was brought to the tarmac by helicopter. The man let the 56 passengers go.

Among other major new stories he covered: the memorial services for President John F. Kennedy and Pope John-Paul II’s first visit to the U.S. in 1979.

But the Chicano Moratorium would prove to be among the most memorable — and harrowing — events he covered after Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies, responding to a possible disturbance at the Green Mill liquor store, fired tear gas as part of an aggressive move to break up the marchers. Before day turned to night, stores had been burned, more than 200 people had been arrested and journalist Ruben Salazar had been killed. Two others were wounded and died days later.

Jarrín, naturally, was in the middle of it all. He was standing with colleague Antonio González across from the Silver Dollar Bar & Cafe when a deputy fired a tear-gas missile into the restaurant, fatally striking Salazar in the head.

Jaime Jarrin, 84, was set to begin his 62nd season as the Dodgers’ Spanish-language broadcaster. Instead, he is home gorging on SportsNet LA content.

The shooting hadn’t stopped when Jarrín left the area around Laguna Park — now Ruben F. Salazar Park — around 5 o’clock. He knows that because a bullet struck his car as he sped away.

“I was so scared,” he said. “They missed my head by 15 inches.”

Jarrín, shaking, made it to Dodger Stadium in time to describe that night’s 3-2 loss to the St. Louis Cardinals, one of nearly 4,000 games he called between 1962 and 1984, when he went 22 years without missing a game.

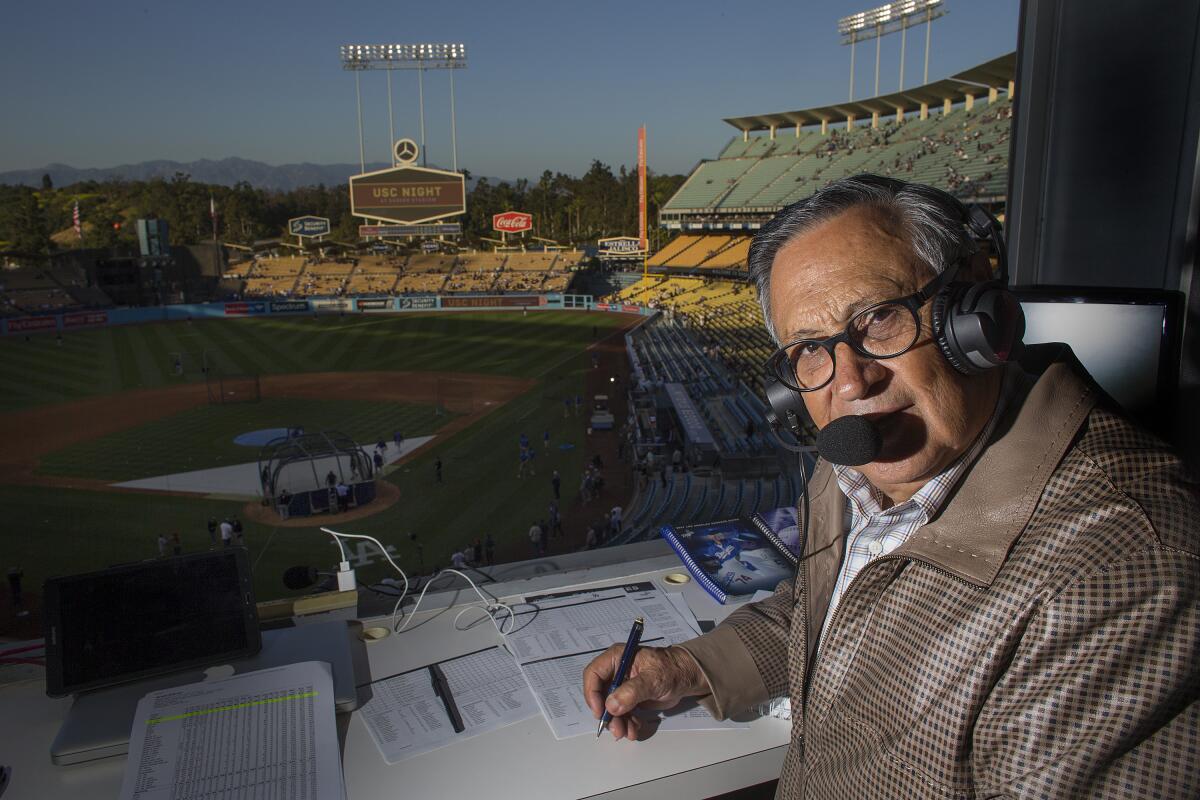

Jaime Jarrín at Dodger Stadium in 2017.

Months later, he covered another Chicano rights protest in Los Angeles that led to the shooting death of a young protester. And while some of the details of that day have been clouded in the fog of time, Jarrín recalled, “He died there. His last words, he was saying, ‘Please don’t kill me. Please don’t kill me.’ ”

Jarrín’s coverage of the moratorium and its aftermath won him a Golden Mike from the Radio and Television News Assn. of Southern California.

“That never happened for a Latino,” he said. “It wasn’t a specific division in Spanish. I was competing with CBS, competing with NBC, all those huge radio stations. And I was able to win.

“It was muy satisfactoria. I really cherish that.”

He won another one a year later for his coverage of Mexican President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz’s meeting with President Nixon in San Clemente; both trophies are on loan to the Smithsonian Institution. But those weren’t the only Golden Mikes in the Jarrín household since son Jorge, then a helicopter-borne traffic reporter, won one of his own for his play-by-play of an airplane pilot’s emergency landing in 1993. It is one of six awards the younger Jarrín has earned for carrying on the family tradition.

“My dad was my role model,” he said. “He had always been primarily a newsman first and has always taken great pride in that.

“I remember my dad always telling me, ‘Just the basics. Keep it simple. The how, what, when and where.’ ”

The elder Jarrín went on to be honored with the Ford C. Frick Award for broadcasting by the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., in 1998, the second Latino to receive the prize. Six years before that he was presented with La Gran Cruz al Merito in his native Ecuador, the nation’s highest civilian honor and the closest thing the country has to knighthood.

That award too is significant because while Jarrín said he was often mistaken for a Mexican during his newsman days, he actually learned his craft in Ecuador, where he covered the national congress and presidential affairs for four years for Radio Quito.

“That was my foundation,” he said. “So when I came to this country that’s what I did.”

He had never seen a baseball game before coming to Los Angeles in 1955, three years before the Dodgers did. But he was such a good reporter and such a quick learner that William Beaton, then-owner of KWKW, told Jarrín to learn the game because he wanted him to describe it to the station’s listeners.

He was cutting back. He was staying home. He missed his wife.

Today Jarrín, the longest-tenured announcer in baseball, has called more games than any other active broadcaster in any language.

Despite his fame, Jarrín, now in his sixth season of calling Dodger games alongside his son on KTNQ-AM, remains both unfailingly polite and humble, traits he has passed on to Jorge. “I can never follow my dad’s footsteps. He’s done all these great things,” his son says.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the pair to work every game from a booth at Dodger Stadium whether the team is playing home or away. And that’s not the only time they spend together. After Blanca Jarrín, Jorge’s mother and Jaime’s wife of 65 years, died last year, Jorge became his father’s housemate too, moving back into his childhood bedroom.

“I missed so many things when he was growing up,” said Jaime, who traveled with the Dodgers during the summers of his son’s youth. “So in a way I am paying Jorge now for the time I missed being with him when he grew up. I really appreciate his company.

“It’s a bendición.” A blessing. “Una bendición muy grande.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.