Commentary: Museums are closed, but you’ll find respite in UCLA’s remarkable sculpture garden

The four monumental bas-reliefs of a woman’s back that Henri Matisse finished between 1909 and 1930 are among the most enigmatic sculptures of the 20th century. They show him refining the figure’s forms — head, limbs, torso, spine — one after the other over the course of two decades.

But they’re a painter’s sculptures. Matisse’s formal progress in his paintings was one inspiration for them, which I stopped by to see the other day at UCLA’s Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden. They’re the pinnacle of that remarkable public collection of some 70 Modern works, which rambles over five acres of the school’s North Campus.

Effectively two-dimensional, the shallowness of the reliefs is primarily a means to control the play of light across the surface of modeled clay, which was then cast in plaster and finally bronze. The tactile modeling-marks Matisse left on the figures with his fingers and tools are like brushwork. Light approaches what a painting’s adroitly handled color could achieve.

African sculpture, which Matisse regularly saw in the window of a Paris gallery on frequent walks through the Rue de Rennes, was another stimulus for the backs. A third was classical Chinese art, which he encountered in the large collection of San Francisco ex-pats Sarah and Michael Stein, his friends and patrons.

And what of the chosen subject — a woman’s back? Paintings by Cezanne, Courbet, Gauguin and other artists surely had an influence. Plus something more.

“Women represent the imagination,” Matisse said late in life to the Swiss art critic Pierre Courthion. The claim perhaps just represents two men talking about something beyond themselves.

Maybe that also explains the slightly voyeuristic quality in relief sculptures that show a woman from behind. With her left arm raised, she leans against a wall. Uniquely identifying facial features have been purposefully hidden.

You can feel a bit like one of the lascivious elders who crept up on innocent young Susanna, naked at her bath, to spy on her — a fictional story popular in Baroque Europe that hinges on moral treachery. That’s one aspect of Matisse that makes him modern, rather than academic. You don’t merely watch a principled narrative play out in his art; instead, you’re an active participant in it.

In fact, that’s what had brought me to UCLA and the Murphy Sculpture Garden in the first place. I missed the active conceptual conversation an art experience initiates. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an art drought, and it was getting to me.

Museums have been closed up tight for months, their tentative reopening plans changing day by day as the course of the disease ebbs and flows. I was inside one that had reopened — in a cautious and limited way — just three days before, when the latest re-closure order was announced by Gov. Gavin Newsom. That was that; out I went.

The solitary visit made for the third shut-down museum exhibition that I had seen but couldn’t write about, since readers couldn’t visit. Granville Redmond’s early 20th century landscape paintings at the Laguna Art Museum were in a holding pattern, joining Ree Morton’s painted reliefs from the 1970s at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the enigmatic Ming Dynasty landscapes of Qiu Ying at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (The Redmond is still installed inside locked museum rooms, where the paintings await another reopening.) So: Murphy Sculpture Garden to the rescue.

It’s an exceptional place (the Hammer Museum oversees it). Unlike most L.A. art galleries, where new art is emphasized, aspects of postwar history unfold across the lawn. Two-thirds of the sculptures date from the 1950s through the 1970s. A dozen come from the first half of the 20th century in America and Western Europe. Only one was made in the 21st century.

That one is on the plaza next to the Matisse. (Incidentally, the sun-drenched plaza could use a bench near the reliefs.) A tall, curved wall of torqued steel, Richard Serra’s “T.E.U.C.L.A.” (2006) forms an almost closed oval shape. A narrow opening invites you inside. There, the tilting enclosure wraps around your peripheral vision, enveloping it in impenetrable steel. Your body just naturally begins to lean with it.

The sculpture pushes a visitor around. The feeling is strange. Walk inside, and shifting spatial perception causes otherwise ordinary and expected physical balance to get vigorously, disconcertingly challenged. Matisse and Serra engage bodily awareness, but in very different ways.

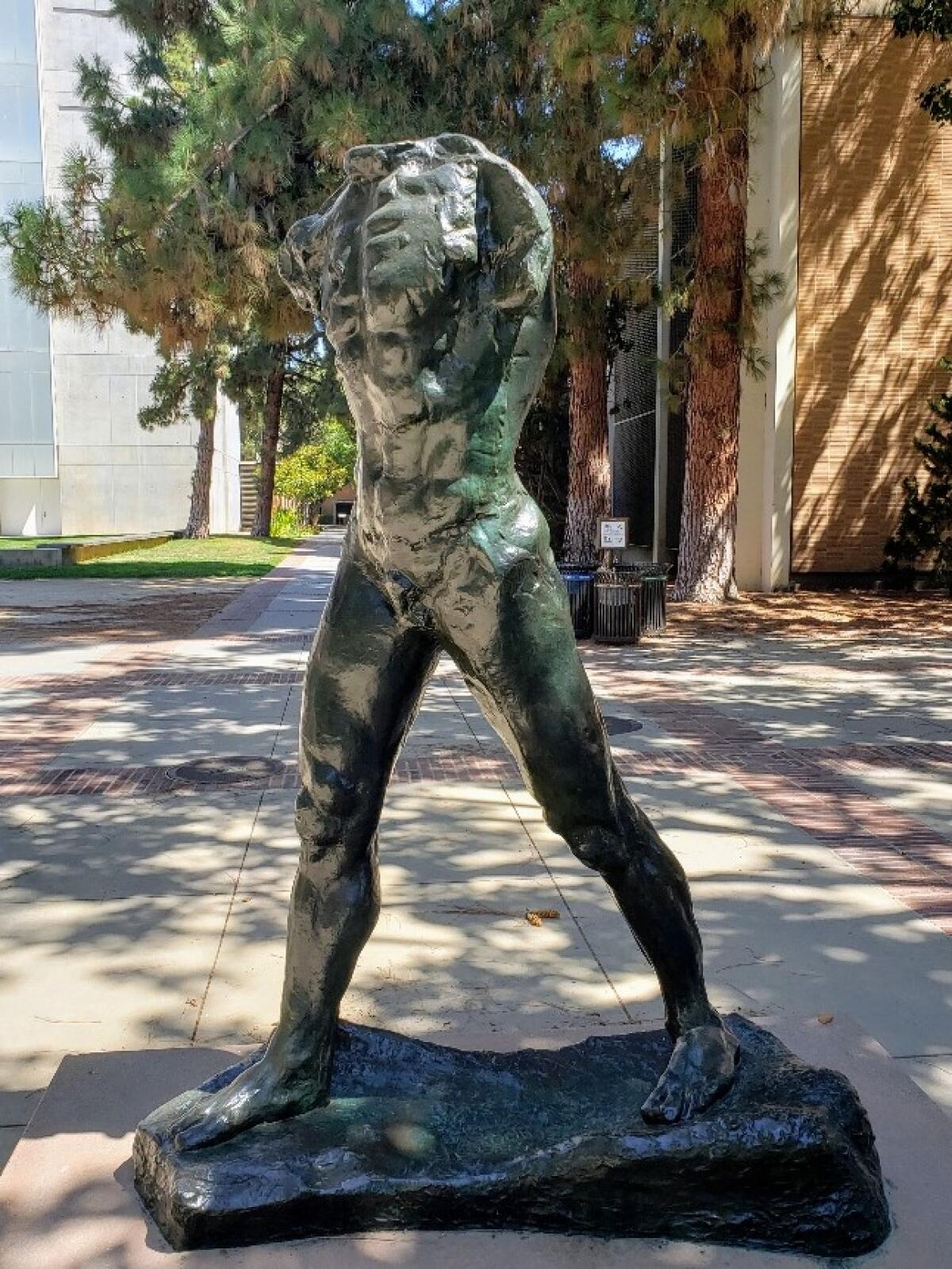

Just past the Serra, on a sidewalk that leads to a grassy field, Auguste Rodin’s 1905 “Walking Man” provides a compelling corporeal twist. Headless, armless and set on a low plinth that approximates the ground plane a viewer shares with the sculpture, this bronze figure is taking a wide stride with straight legs and both feet planted firmly on the ground.

Nobody can walk like that; it’s impossible. Copy the pose yourself, and you discover your virtual immobility.

Yet Rodin’s life-size figure, muscles and tendons rippling beneath surface skin, nonetheless appears dynamic, not static. The fragmented body recalls the headless and armless sculptures we know from Greek and Roman antiquity, like “The Winged Victory of Samothrace” at the Louvre, while that impossibly flat-footed, straight-legged stride goes back to the colossi of ancient Egypt. “Walking Man” marches from the mists of time into the space of modernity.

For years, Matisse owned a Rodin plaster bust of the wild-haired radical journalist Victor-Henri Rochefort, once in the possession of painter Édouard Manet. He understood the sculptural intensity of Rodin, whom he knew as a young man. A great feature of the Murphy Sculpture Garden is the unspoken invitation to ricochet around various works like that — Matisse to Serra to Rodin, all artists working at the top of their game.

Not everything here is superlative, of course, but enough is to keep the engagement going. There are lots of famous names: Arp, Bourdelle, Calder, Miró, Noguchi, Voulkos and more. And there are surprises.

Anna Mahler’s 1961 “Tower of Masks” is arguably the finest work by a not well-known Austrian sculptor — a piled-up column of primitive, blank-eyed but emotive faces carved from pale sandstone. The precarious, three-dimensional balance and visual rhythm of the masks is executed through a Brancusi-like practice of direct carving, common in non-Western art but not much employed in 1960s America. (Mahler taught at UCLA.) The sculpture is a totem, both in form and subject.

A totem-subject of diverse masks, emblematic of artists’ creative lives, is unsurprising for Mahler. She led an active personal life (five husbands, two more than her mother, composer Alma Schindler). Rodin executed a commissioned bust of her father, composer Gustav Mahler, and her stepfather was architect Walter Gropius. Being a woman navigating male-dominated creative fields required grit.

In fact, only four women are represented in the Murphy Sculpture Garden — Mahler, Deborah Butterfield, Claire Falkenstein and Barbara Hepworth — among 47 men. Almost all the artists are white. Many works entered the collection following museum exhibitions in L.A., which is one indicator of just how traditionally blinkered the city’s art scene had been.

The garden is itself a kind of period piece — contemporary because mostly chosen in the 1960s and 1970s, a time when art dramatically changed, often led by sculpture.

Minimal, Conceptual, Post-Minimal — younger artists in those years were shaking up things, but you won’t find much of that here. One modest exception is a Minimalist structural “fence” of repeated, intersecting white cylinders by William Tucker. (The young British sculptor credited the syntax of limbs and spine in Matisse’s “Backs” as an inspiration.) The more recent Serra is another.

Neither one is a sculptural object in the conventional sense. Anthony Caro’s “Halfway” is abstract, but the relationships among its steel I-beams painted red and lying on the ground recall the composition of torso and limbs in an odalisque lolling on a divan. The ballooning bodily forms of Gaston Lachaise’s Amazonian bronze woman, who looms 7 feet tall, are fantastical; but her swollen voluptuousness still describes a discrete figure in contained space.

In contrast, Tucker’s cylinder forms could repeat into infinity, while Serra’s steel plates take a slice through curved space, eliding sculpture’s traditional separations between an object’s inside and its outside. These works are outliers in UCLA’s garden, which is primarily home to an anthology of classic Modernist sculpture — artistic ideas born in Europe and transferred to the United States after World War II.

One feature of that Modernist legacy assumes a distinct poignancy today, when hospitals overflow, an economy is in free-fall and long-hidden social stresses are brutally exposed. Over and over, these sculptures refer to Western antiquity — to decay and dissolution and an archaic world in need of overhaul and renewal. Modernity in sculpture wasn’t just about looking toward the future; it was about starting over, a daunting task that required acknowledgment of past limits and even failure.

Lachaise’s Amazon is blowing up Classical tradition. Rodin’s “Walking Man,” striding into a new world, tears it apart, limb from limb.

Hepworth’s punctured bronze “Elegy III” — a sleek organic form upright on a pedestal — pokes a lamenting hole in it, physically letting nature in. The rough-hewn ancient forms of Henry Moore’s “Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 3” seem poised to interpenetrate, like a plug and socket — a sculpture virtually copulating with itself to bring forth something new.

Chicago-based Richard Hunt, the only African American artist represented in the collection, asks “Why?” in a metal abstraction of upright organic forms suggestive of a hand fused with a bonfire. The composition is like an emblem for Ogun, Yoruba god of iron, or Vulcan or Hephaestus at his forge on Mount Olympus.

And Matisse — well, the more Matisse pared down his forms, the more primal his figure became. Leaning face-first on her arm against a wall, she’s anxiety and foreboding personified.

That wailing wall could be Alberto Burri’s monumental “Grande Cretto Nero” — a “large black crack” that’s a massive expanse of glazed clay inspired by visits to the dried-up lake bed of Death Valley. (The late Italian artist wintered in L.A. for decades.) Seven hundred chunky forms in a wall 49 feet wide and 16 feet high are cracked and riven, a macrocosm matched by the microcosm of hairline crackling in the shiny black glaze.

Burri once described his work as “the archaeology of the future,” and his UCLA sculpture is surely that.

The battered wall unintentionally conjures a defining episode in the life of Franklin Murphy (1916-1994), the Missouri-born physician who became UCLA chancellor (and later chief executive of Times Mirror Co., The Times’ former owner). The doctor initiated the sculpture garden project in 1963, before the city had any serious art museums. As a medical student in Munich, Germany, in 1936, Murphy had witnessed Adolf Hitler’s notorious “Degenerate Art” exhibition, which first mocked, then criminalized Modern painting and sculpture, all while promoting the artistic fraud of authoritarian state propaganda.

An 800-pound marker for the Jefferson Davis National Highway has been removed from view. A college student’s email prompted the change.

That’s another rather grim reason the Murphy Sculpture Garden is worth visiting right now, as fights over kitsch Confederate statues erupt and grandiose pandering unfolds at super-kitsch Mt. Rushmore. A place like UCLA’s sculpture garden probably couldn’t be built today — partly because its lovely open acreage has become rare at the crowded campus, and partly because sculpture collectively worth hundreds of millions of dollars has been put far out of reach by the explosive investment market for Modern art.

But there it is, just when we needed it. I spent a couple lovely hours, absorbed. In the midst of a crushing health catastrophe, it’s just what the doctor ordered.

Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden

Info: Go to hammer.ucla.edu/collections for a link to garden information, including a map as well as walking and driving directions (UCLA Parking Lot 3 off Hilgard Avenue).

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.