Female, trans and nonbinary writers got their big break. Then came COVID-19

Empty theaters across the country stand like time capsules of what was and what might have been. Sets sit idle on stages that have not changed since mid-March, when the coronavirus first laid siege to the nation, forcing a wave of canceled shows and deferred dreams.

At off-Broadway’s Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, scenic designer Angelica Borrero’s family home is trapped in amber: a refrigerator covered in greeting cards and bills, a couch with a homemade quilt and mismatched throw pillows, and behind that, a bedroom with a single unmade bed, all for actors who took bows on March 14, never to return.

“It’s oddly preserved under a layer of dust right now,” playwright Ren Dara Santiago said of the set for “The Siblings Play,” which was forced to end its world-premiere run during previews, four days short of its official opening night.

Santiago’s canceled play is part of a list called “The List,” created by activist collective the Kilroys. Since 2014 the Kilroys have called attention to the lack of gender parity in American theater by putting together a yearly survey of unproduced and underproduced plays by female, trans and nonbinary writers.

This year’s list — like everything touched by the global devastation unleashed by the coronavirus — is different. It is a living document of every postponed or canceled play written by the underrepresented groups that the Kilroys seek to champion.

On the collective’s website, the list is presented as a heartbreaking timeline of lost art, necessary art, groundbreaking art, unconventional art, art created by voices aching to be heard.

The timeline has 150 productions, beginning with Lorene Cary’s “My General Tubman,” about the lasting impact of Harriet Tubman, which ran for two months at Arden Theatre Company in Philadelphia before the remainder of its run was canceled on March 13. The list ends with Sanaz Toossi’s “English,” which was scheduled to stage its world premiere at Roundabout Theatre Company in New York on Nov. 12. It delves into the lives of four adult students in Iran as they prepare for an English language test.

Freelance director and Kilroys member Jennifer Chambers said this year’s list rose out of the urgency to highlight the depth and breadth of the lost work. She urged theaters leaders across the country to make sure these plays do not stay lost — that they be picked up again when the pandemic is over.

“We need to serve this already underserved and underrepresented population and really amplify their voices in order to express that these plays cannot be forgotten,” Chambers said. “And as theaters announce their new seasons, we are hoping that these plays are a part of that.”

The Kilroys list, which normally features about 30 plays, has become a go-to resource for theaters looking to identify promising work. At a time when the industry is making strides in diversifying the voices it amplifies and the stories it tells, the cancellation or postponement of so much work — particularly by young writers just entering the so-called talent pipeline — is a reminder of how fragile progress can be.

The Times interviewed three playwrights on this year’s list about the joy of seeing their work finally land onstage and what happened when COVID-19 turned off the lights.

In the Zoom Zoom Room

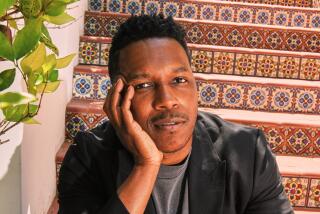

Through February and the beginning of March, playwright Roger Q. Mason was hard at work on “Lavender Men,” slated to open at Skylight Theatre in Los Angeles on April 18. Then coronavirus hit, and everything changed.

Optimistic and effervescent, the nonbinary writer — who emphasized that this interview represented a new embrace of they/them pronouns — has been looking for ways to wring positivity out of tragedy. Mason took to what they call the Zoom Zoom Room, working with the production’s creative team and workshopping the play through the online video platform. The result is something Mason feels exceedingly proud of.

“Out of the madness and tremendous peril in which we found ourselves, a few good things could bloom, and I found that to be a marker of hope,” Mason said.

Mason calls “Lavender Men” a “queer historical fantasia,” which is a tip of the hat to Tony Kushner and his play “Angels in America,” subtitled a “gay fantasia on national themes.”

“Lavender Men’s” protagonist is a gender-nonconforming, plus-size person of color named Taffeta (played by Mason) who uses the play to imagine a romance between Abraham Lincoln and his assistant Elmer Ellsworth to better understand how Taffeta came to be the person she is.

The play, Mason said, was born out of a cry for community and has morphed into something greater during what has been an important time for the writer artistically. Despite the tragedies and anxieties born from COVID-19 and national protests calling for racial equity and social justice, the emerging conversations about the need for cultural change have been inspiring.

“What’s really exciting about this time is that voices that wouldn’t otherwise be heard are now being put center stage, and I think that is so important for the health of our profession,” Mason said. “Equity and inclusion are supremely important.”

Skylight has committed to including “Lavender Men” in its 2021-22 season.

‘I just kind of shut down emotionally’

It was late afternoon on March 12 and Azure D. Osborne-Lee emerged from therapy, checked his phone and saw the message: “Your run has been canceled.”

“I just kind of shut down emotionally,” Osborne-Lee recalled of that moment when his play “Mirrors” closed just 10 days into its run at Next Door at NYTW, an initiative of New York Theatre Workshop.

“Mirrors” takes place in a small Mississippi town in 1960. It explores the interconnected lives of three African American women, including a mourning teen daughter and her mother’s ex-lover, a woman the girl doesn’t know but with whom she must move in after the mother’s death.

Osborne-Lee had been working on “Mirrors” on and off for 10 years before he landed his first world premiere. The playwright, trans and Black, felt misunderstood by reviewers, most of whom were cisgender and white. That’s why he was very much looking forward to hosting that evening’s queer theater night and connecting with his target audience.

As difficult as the premature closing was, Osborne-Lee has found more than a few silver linings. Being included on the Kilroys list is one — to be acknowledged with peers experiencing the same sense of loss.

“I feel like it’s already opening some doors for me, recognition-wise,” Osborne-Lee said. “It took so long to get that first world premiere, and my fear is that I would kind of go back to zero.”

That hasn’t happened. Osborne-Lee’s play “Crooked Parts” was included in the online version of Rattlestick’s Pride Plays festival in June, and other engagements are percolating.

The set for “Mirrors,” however, still sits lonely at Next Door. Osborne-Lee doesn’t know if it ever will be used again.

A play in purgatory

“The Siblings Play” was to be playwright Santiago’s professional debut. She looked back on those eerie, early days of the coronavirus crisis in New York as if they were a kind of fever dream. The city felt like an island preparing for a hurricane. Then one day in the middle of rehearsal, Rattlestick Artistic Director Daniella Topol arrived and said, “New York is shutting down.”

Santiago recalled being so intensely involved in tech rehearsals and previews that she didn’t have a clear grasp on how severe the pandemic had gotten. Her team had been filling seats as best as they could, and they were peripherally aware that the theater was not full because of the coronavirus threat.

Still, the previews had been a dream come true. The play tells the story of a teenage girl and her two brothers, who must take care of one another in their Harlem apartment after being abandoned by their parents. One show was filled with Santiago’s target audience: teenage girls from the city. During another preview she sat behind a young man who was trying hard not to cry — fronting for his friends that a scene hadn’t affected him as much as it did.

The staging of the play, Santiago said, was something she once thought might never come. When the reality of the cancellation set in, Santiago said, “I remember being really upset and trying not to cry and being angry instead.”

Her heart broke most for her creative team. Its devotion can be seen in the set that remains in the theater. A family photo on a refrigerator, a baseball cap hung by a door, a reading lamp that might never turn on again.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.