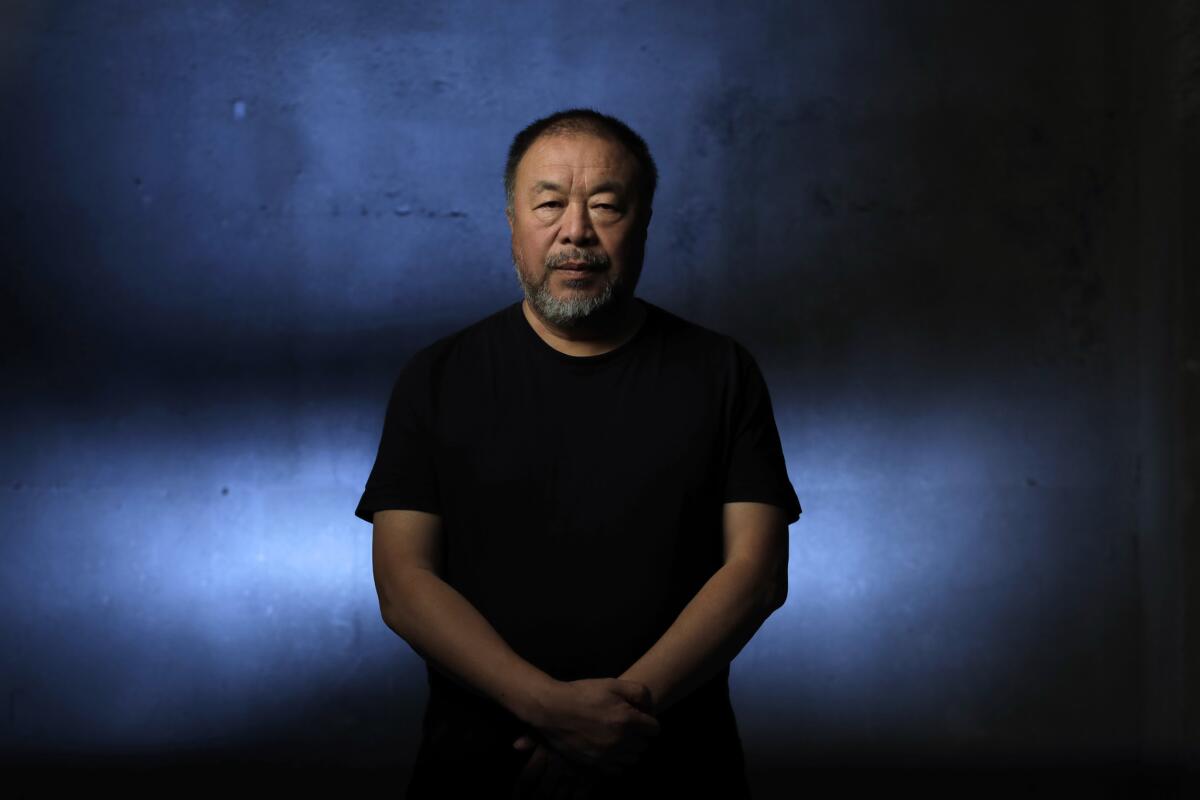

Ai Weiwei on activism in the U.S., his art response to COVID-19 and a secret Wuhan film

Ai Weiwei’s mother is visibly pained recalling her son’s life as a newborn.

“He was born at his father’s darkest time,” she says in the new documentary, “Ai Weiwei: Yours Truly,” released earlier this month from First Run Features.

The film, directed by Cheryl Haines, co-directed by Gina Leibrecht and available to stream through select theater websites, explores the Chinese artist and human rights activist’s 2014 public art intervention, “@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz.” And it has much to say about prisoners of conscience and the role of art in both promoting freedom of expression and providing salve to the wrongfully incarcerated.

But it also offers a rare and captivating window into the artist’s early years, growing up in exile on the edge of China’s Gobi Desert. In 1957, explains Ai’s mother, Gao Ying, his father, the poet Ai Qing, was banished to a forced labor camp by the Chinese Communist government. His mother followed, the infant Ai cradled in her arms, his siblings in tow.

Ai spent his entire childhood in exile. “This left a huge shadow on me,” he says in the film. But that shadow grew, eventually engulfing him and becoming the catalyst for a life devoted to art and activism.

At a particularly urgent and volatile time in U.S. history, one seeing prolific protests and a nationwide reckoning over systemic racism in this country — not to mention a devastating global pandemic — we turned to the artist for his thoughts on, well, the current state of things. Here’s the edited conversation.

“Ai Weiwei: Yours Truly” is about the exhibition on Alcatraz. But it’s also about the persecution of your father and your childhood in exile. How did growing up under those circumstances shape you as a human rights activist?

My early childhood was spent with my father, Ai Qing, a national poet punished by the state, sent into exile in China’s northwest, and forced into manual labor. He was ordered to clean the most primitive latrines. I watched him stand in front of that [dirty] hole each day and that formed my consciousness of humanity and aesthetics. The particular moment [of awakening as an activist] lasted years.

My experience is not unique in China. There is a long history of countless writers and intellectuals who were put in jail, exiled or who simply disappeared. Today, anyone who dares to question the authority of the party or who state their belief in freedom of speech or in human rights could face the same consequences. I know that struggling and fighting will not necessarily achieve progressive social change, but it is necessary for my existence and gives light to life itself. Often, for that humble reason, one can lose their life.

What are your thoughts about the protests sweeping the U.S. right now, addressing anti-racism and police brutality, among other things?

I only sense the moment happening in the U.S. from a distance. What I can see is the deterioration of a major power on the edge of collapse. The issue is not simply the deeply rooted racism and other related issues, such as gun violence and police brutality, but rather a moral and ethical vacuum in the time of global corporate authoritarianism. We are living in an extremely divided world where for too long, discussions on protecting humanity and human dignity have been missing. As a result, social divisions have continued to widen. Unless we solve the real problems, the symptoms of this chronic illness will persist.

So much of your work is about freedom of expression. What do you think about the debates over “cancel culture” and the recently published letters in Harper’s Magazine and The Objective?

In my view, there should be the right for any idea or thought to be expressed. It doesn’t matter if you are on the left or the right. It’s essential for our intelligence, our sense of right and wrong, to be fully, healthily developed. I can sense in the U.S., or in Germany, both places I have spent some time living in, where there is a clear tendency to dismiss ideas which may be seen as unsuitable due to its historical content, or where human intelligence and our capacity to face, challenge, and judge ideas is underestimated. Regardless of your political affiliation, you will end up [like] a Nazi if you can’t allow certain ideas from being expressed.

You moved from Berlin to the UK last year. Where are you living, what’s it like there and how has the pandemic affected your life, personally?

I moved from Berlin to Cambridge in the UK. The reason for the move was to accompany my son for his continuing education. I still have a studio in Berlin.

The pandemic does not affect my life at all. I have long experienced “social distancing,” since I was born the son of an enemy of the state. I have lived in detention and soft detention, placed under surveillance, watched and followed like a social disease in China. In the West, I’m a foreigner. I can easily experience more foreignness in my ideas than my social status in this society. That might take a lifetime to adjust, maybe it cannot be changed.

Life is so comfortable in the English garden that is Cambridge, where the weather has been beautiful this spring, and I have no complaints.

This past spring, you designed more than 22,000 masks featuring imagery from your work — sunflower seeds and an upright middle finger — with the proceeds going to coronavirus relief. Tell us about meeting the moment with art.

The idea is small, almost not worth mentioning, but I tested it during a most dramatic, historical moment. Too often, moments like this lack initiative and action. I am happy with the result and the great response from the public, which has made the project meaningful and will support many vulnerable people, including those long forgotten such as the refugees. As an artist, my true struggle is to answer the call of the moment, to respond with my effort and become a part of it. It is endless, but that’s fate.

You’ve said that the pandemic is a humanitarian crisis as much as a health crisis. How so?

COVID-19 is the only crisis that confronts the global community, no matter the geopolitics, economic situation, or religious differences. Nothing else has allowed us to so plainly examine our humanity, intelligence, scientific development and government control. We have found how fragile human society can be, so much more fragile than we could have imagined. It suggests that more unthinkable events could follow. I think this pandemic is a humanitarian crisis because it tells us how precarious humanity [is] and shows us the possibility that it can disappear altogether.

What do you think about how China handled information around the virus outbreak?

After the first patients were diagnosed, China covered it up and for quite some time gave misleading information about the nature of the disease. The authorities also cracked down on doctors that released information about the new disease. As a consequence, this gave the possibility for the disease to quickly spread. As people filtered out of Wuhan, [it furthered] the possibility for this to spread around the world. The next effort that China made was a military-style lockdown of this city of [more than] 10 million people. The effect of the control was very efficient and it stopped the disease from further spreading, but we still do not know the real number of those infected and those that have died. China is very good in keeping secrets.

What happened in China is not just about the pandemic. It raises the question of whether the West can continue to see China as a partner without basic transparency and trust in its political structure. This struggle will last longer than the disease itself. It is painful, but has become necessary. China stands as a challenge to the West, not just economically but with cultural and social differences and conflicts in ideology.

What are you working on now, what’s next?

During this lockdown period, my studio has finished the production and post-production work for three films, which will come out very soon. One of the films is about the Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh, where over 1 million refugees reside. It is about their existence and struggle. The second film is about the uprising in Hong Kong last year. We have seen the result with China tightening its control, which will transform Hong Kong into just another Chinese city. The last film is the one we started last but have finished first. This film is about the pandemic in Wuhan. I cannot tell you more at this time.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.