The new radicalism of Black playwriting

The recent renaissance in American drama would be unthinkable without the energy and imaginative daring of a group of gifted young Black playwrights.

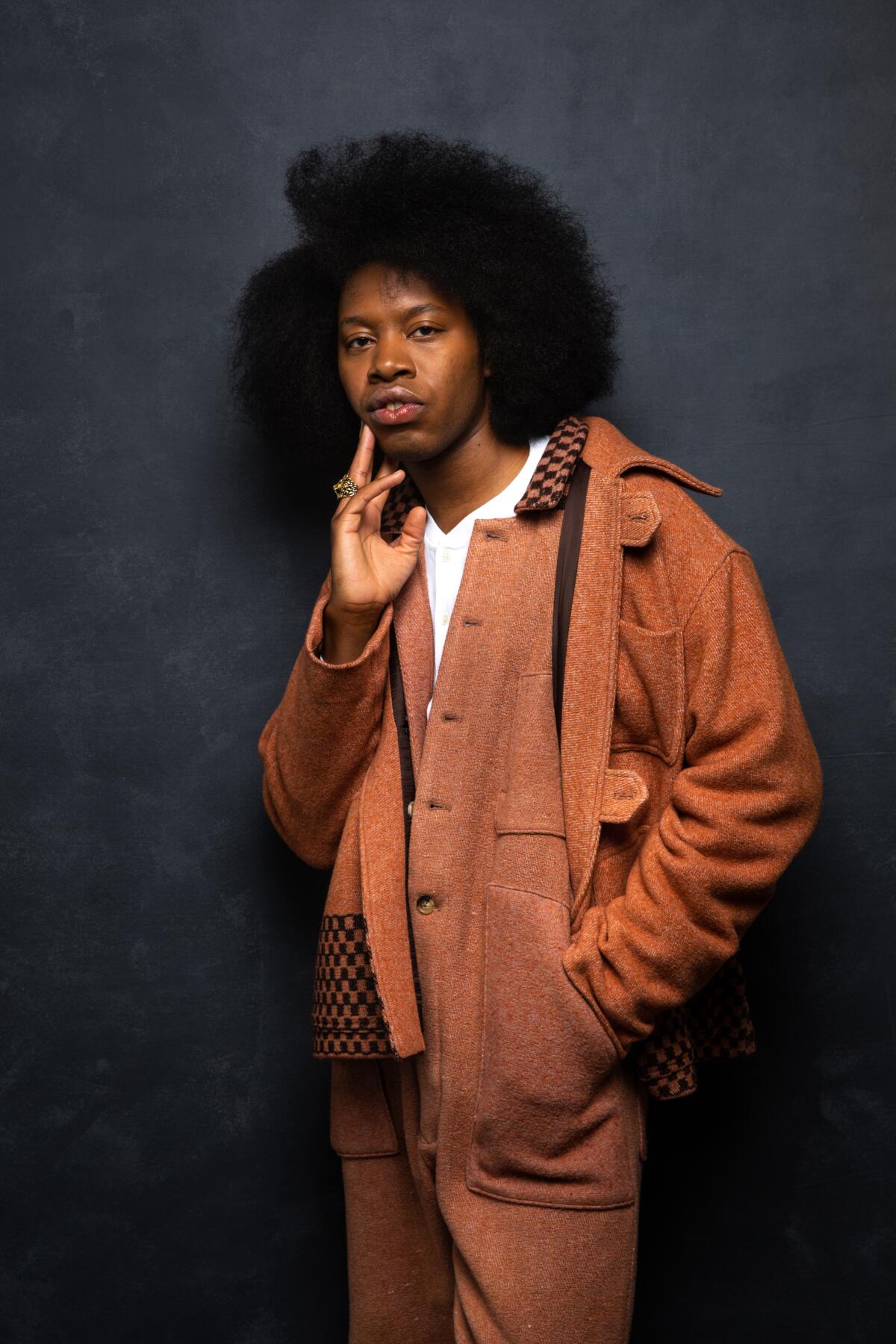

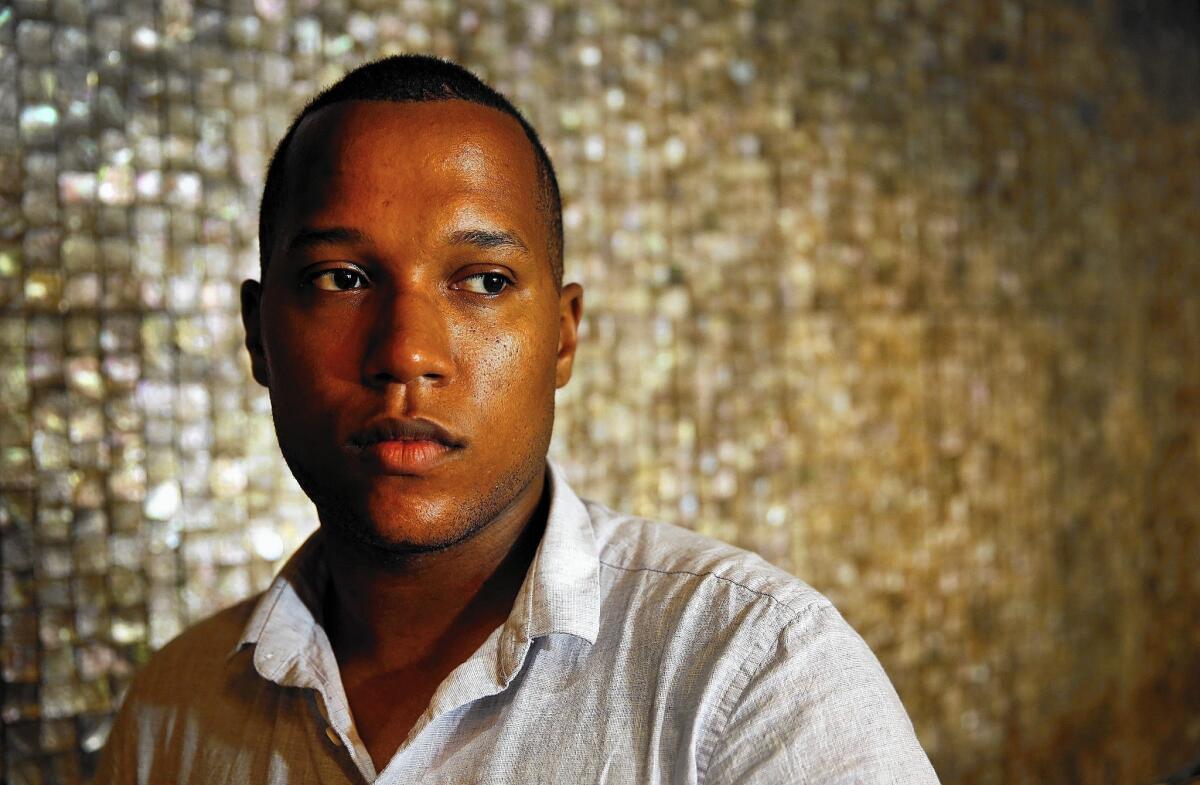

Talents such as Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (“An Octoroon”), Jackie Sibblies Drury (“Fairview”) and Jeremy O. Harris (“Slave Play”) are too individual and innovative to be lumped into broad categories. But these writers are united in their dismantling of conventions that have historically marginalized African Americans from the American story.

There was a time when dramatists felt obliged to win the favor of the predominantly white audiences of our most prestigious playhouses. Work could challenge theatergoers at these venues, but only within limits. A play’s societal critique could cut deep as long as it didn’t offend the sensibilities of ticket-buyers. Producers enforced this unwritten law.

Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin the Sun” and August Wilson’s 10-play cycle depicting African American life in the 20th century balanced uncompromising truth-telling with stories that engendered emotional investment and reward. Broadway realism was mastered and reengineered to comfortably introduce the white mainstream to characters and experiences outside the traditional scope of weekend matinees.

The descendants of Hansberry and Wilson have extended their paths in unforeseen directions. The versatility of dramatists such as Suzan-Lori Parks and Lynn Nottage, both of whom have refused to be confined by their past successes, has been a powerful source of renewal for the American theater.

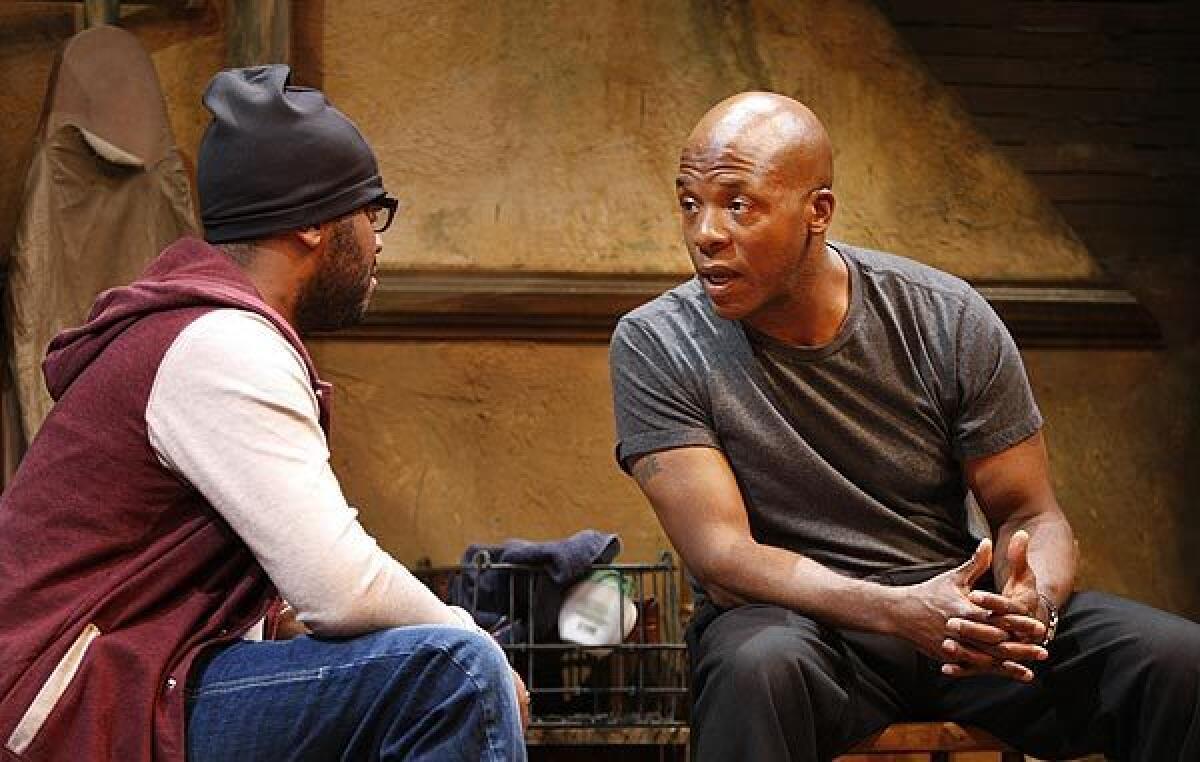

Parks left behind the experimental collages of “The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World” and “The America Play” to explore storytelling in syncopated (the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Topdog/Underdog”) and epic blues forms (“Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2, & 3”). Nottage has moved from the quietly devastating realism of “Intimate Apparel” to the more sweeping theatrical canvases of her Pulitzer Prize-winning plays, “Ruined” and “Sweat.”

Hansberry and Wilson were hardly monolithic either, so this restless inventiveness should come as no surprise. The history of African American playwriting, which contains voices as bravely pioneering as Alice Childress’, as acutely interior as Adrienne Kennedy’s and as militantly electric as Amiri Baraka’s, is too richly various to be reduced to schematic generalizations.

But something is palpably different among playwrights of the millennial generation, who are envisioning, demanding and conjuring into existence a new and more diverse spectatorship. Their relationship with audiences, rather than operating in the quid pro quo manner of our commercial theater or the insider code of the avant-garde, is charged with protest, clarifying anger and targeted love.

Coming into public prominence in the age of Black Lives Matter, these writers aren’t satisfied with the neutrality of non-racism. Their stance, mirroring the cultural shift sweeping the nation in reaction to Donald Trump’s divisive presidency and the deadly racial bias in our criminal justice system, is actively anti-racist.

Adherence to the old rules is no longer a given, and dramatic values once considered sacrosanct are being rethought. Watching the rebroadcast of the film version of Anna Deavere Smith’s “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992” on PBS, I was made aware of a yawning aesthetic gap.

Naturally, I was struck by the resonance of this documentary drama about the aftermath of the 1992 Rodney King riots with today’s Black Lives Matter protests across the country. But I was equally struck by the way Smith’s complex empathy extends even to the most morally benighted characters. This isn’t sympathy for devils, but a determination to understand all viewpoints — a core dramatic principle that now seems of another time and place, a remnant of a world where there was still a flicker of belief that democratic progress could be achieved by working patiently within systems.

Smith was performing for a majority white audience, and her social justice mission wasn’t to satirize but to humanize. In embodying characters based on real-life people she interviewed, she might seize on humorous gestures or quirky speech patterns. But having been invited into largely white institutions, she made it her mission to give everyone a seat at the theatrical table.

That table has been, if not turned upside-down, then thrust into a contested spotlight. Today’s work rebuffs the presumption of audiences long conditioned to believe that the theater was speaking to them and only to them. Harris, who told me he was extremely proud to have obtained a producing credit for the Broadway premiere of “Slave Play,” campaigned to designate select performances of his drama as “Black Out” events, held primarily for Black audiences. This simple act demonstrated that even the whitest of cultural spaces can be demographically reversed.

To challenge traditional hierarchies of spectatorship, Black playwrights have made it deliberately difficult for theatergoers to find their footing. Drury’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning “Fairview,” which had its premiere at Soho Rep., and Harris’ “Slave Play,” which had its off-Broadway debut at New York Theatre Workshop before moving to Broadway, set up worlds that are revealed to be theatrical ruses — a hall-of-mirrors effect designed to keep everyone second-guessing the stage action.

Jacobs-Jenkins perpetrates a different metatheatrical subversion in “An Octoroon,” his highly esteemed 2014 work that had its premiere at Soho Rep. A postmodern colloquy with Dion Boucicault’s 19th century melodrama “The Octoroon,” the play introduces a surrogate, BJJ. While putting on whiteface, this stand-in for the author recounts the therapy session in which the idea of doing a play based on Boucicault’s drama first came about.

The jokey monologue establishes a rapport with the audience, but the banter is rather manic, filled with unreliable narration and volatile humor. BJJ wants the audience on his side, but he doesn’t want theatergoers to presume that they know him or can understand the workings of his mind as a Black playwright: “I can’t even wipe my ass without someone trying to accuse me of deconstructing the race problem in America.”

An open letter protests systemic racism in the American theater. How can we can get back on track? Start by reading the plays providing a roadmap.

Aleshea Harris, another rising playwright, doesn’t pull any punches in delineating the ground rules for her play “What to Send Up When It Goes Down.” Before the audience for this scripted communal ritual, written in response to the chronic police shootings of Black people, is admitted into the playing area, the following words are spoken:

Let me be clear: This ritual is first and foremost for Black people.

Again. We are glad non-Black people are here. We welcome you but this piece was created and is expressed with Black folks in mind. If you are prepared to honor that through your respectful, conscientious presence, you are welcome to stay.

Once passed over in polite silence, the white privilege of theatergoers is now being deconstructed as part of the drama. “Fairview” concludes with Keisha, the teenage daughter in a Black family that has been placed on exhibition, stepping out of the frame to ask white audience members to change places with her. She takes a seat in the house while white theatergoers sheepishly make their way to the stage. Her distraught request is impossible to ignore:

Leave your coats. Leave your bags. Leave your things.

Just stop worrying about your things for a minute and worry about where you can go what you can do to make space for someone else for a minute, if you could.

“Fairview” doesn’t simply convey a message about the warping power of the white gaze. It enacts the experience, purposefully discommoding that part of the audience that has long expected plays to gratify their emotional pleasures and endorse their sense of moral righteousness.

“Slave Play,” a conceptual comedy infused with as much acid as anguish, builds to a climax in which Kaneisha, the Black partner in a group of interracial couples undergoing an experimental treatment called Antebellum Sexual Performance Therapy, has an epiphany that Jim, her lover, is infected with a virus. This pathogen is unnamed and undiagnosed, but it’s clear that the disease in question is white supremacy.

Kaneisha’s eruptions in the last moments of “Slave Play” were especially potent on Broadway. A wall of mirrors on the set reflected the audience’s image, making it possible to see the reactions of individual theatergoers as Kaneisha indicts Jim for being inescapably part of the history of oppression. At one of the the talk-backs after the show, a white woman erupted in fury, “I don’t want to hear that white people are the [expletive] problem.” The clip went viral and more or less confirmed the nerve-hitting truth of Harris’ play.

Jacobs-Jenkins uses comedy not simply to disrupt and problematize the relationship between playwright and theatergoer, but to spring on a captive audience some horrific historical reality. In “An Octoroon,” a postcard showing a lynching cheerfully attended by white people is projected onto the back wall as an equivalent for what was called the “sensation scene” in melodrama, devised to thrill spectators. In “Appropriate,” his 2013 play that had a production at the Mark Taper Forum in 2015, lynching photographs and lynching memorabilia are also included, but the coup de théâtre occurs when a young boy runs down the stairs wearing a KKK hood that he’s unearthed in a white family’s ancestral home that’s being auctioned off to pay the bills.

These playwriting maneuvers are intended to afflict some edifying discomfort on white theatergoers, who are not permitted to duck or hide from the collective past. The cost of a ticket doesn’t buy anyone an escape from America’s original sin of slavery or its enduring legacy of systemic racism.

If the work has a polemical edge in this period of protest, the questions that are being explored are the same ones that Parks laid out a generation ago in her essay “An Equation for Black People Onstage”: “Can a White person be present onstage and not be an oppressor? Can a Black person be onstage and be other than oppressed? For the Black writer, are there Dramas other than race dramas? Does Black life consist of issues other than race issues?”

Space is being cleared for better answers. Institutional progress has been slow, unconscionably so. But the new radicalism of Black playwrights is helping to bring about the day when they won’t have to feel like guests in the American theater again.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.