A 2.2-mile L.A. memorial says their names: George, Breonna, Corey ...

A chain-link fence circling the Silver Lake Reservoir is the canvas for a new art installation protesting police brutality, with colorful fabric woven into the fence spelling out the names of unarmed black people who have been killed across America at the hands of police.

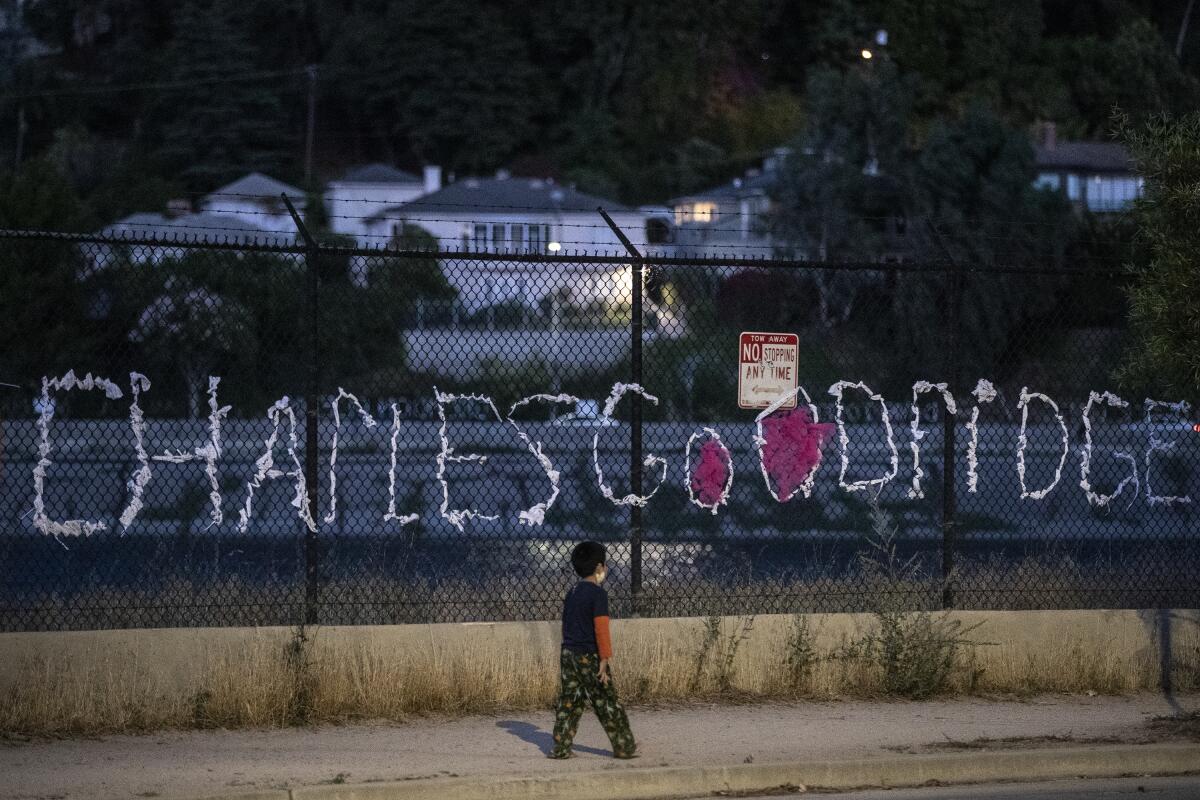

“Charles Goodridge” — who was 53 when shot by an off-duty police officer in Houston in 2014 — is rendered in soft cotton sheets specked with navy dots, the O’s filled in with pink tulle. It rippled in the wind on Saturday afternoon as the project was nearing completion. “Corey L. Tanner” — 24 and shot five times in 2014 in Espanola, Fla., by an officer who mistook Tanner’s bottle of cologne for a gun — is drawn with torn, floral cloth that hung loosely over the swaying, dried grass. “Euree L. Martin” — who died at 58 of a taser-induced heart attack in 2017 while walking in Milledgeville, Ga. — is woven partly with sparkly blue material that shimmered against a sky of the same color.

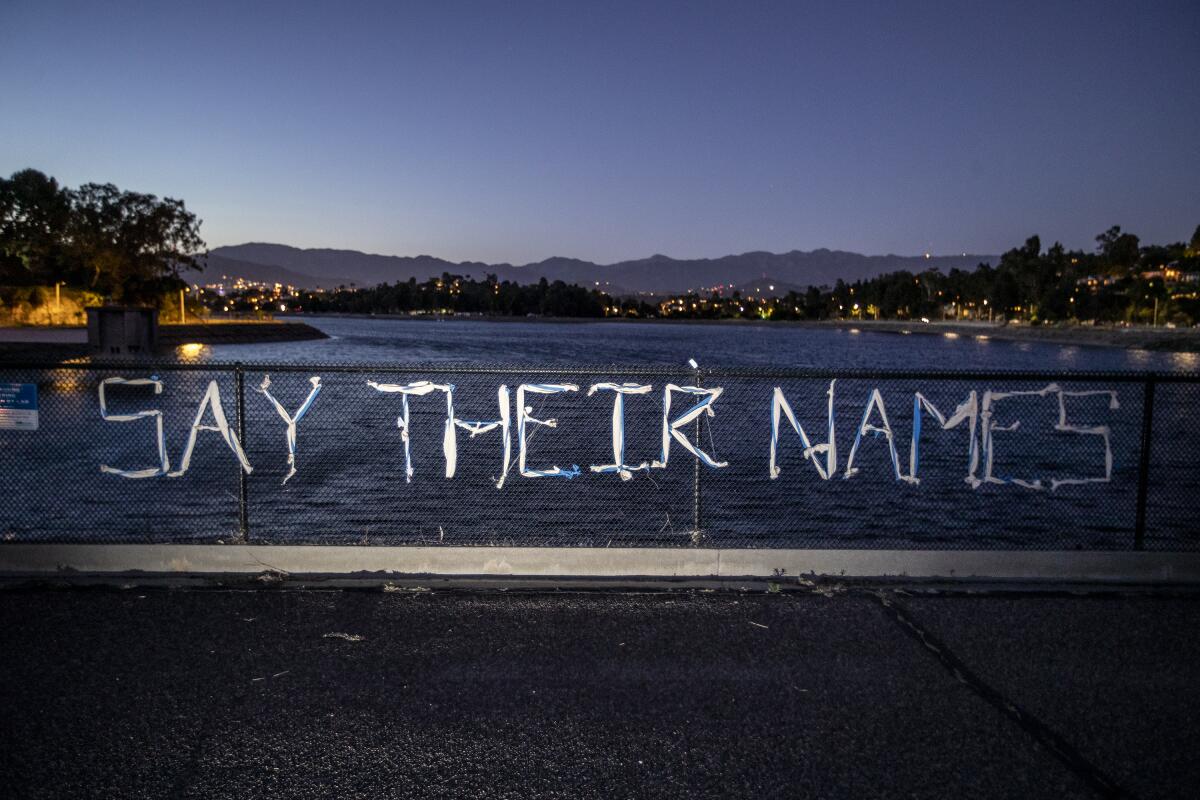

“Say Their Names: Silver Lake Memorial” honors more than 100 individuals.

“And if the reservoir was 10 times as big, we would still have an abundance of names left over,” said project co-organizer Eli Caplan. “We may hear about the George Floyds, the Breonna Taylors. But for each of those, there are hundreds and hundreds of other names that get lost. This is a way to acknowledge them.”

Caplan, who identifies as Jewish Puerto Rican, said organizers chose the reservoir location because of its high visibility in the city. Of about 150 mostly local participants so far, he said, “the vast majority were privileged white people, that was the reality. It’s so important to bring the names of black people into a predominantly white space. But this isn’t a Silver Lake problem. It’s a U.S. problem, it’s an everywhere problem.”

Close up, the ragged, flowing or tightly rolled fabric — classic plaid, sheer chiffon, stained pink organza, screaming-orange rayon, vintage corduroy curtains, silky scarves — have an abstract feel, a collage of contrasting textures shot through with rustic knots and fraying edges, textile-stitched hearts and fresh flowers. From afar, the names of the deceased, many several feet high and each spaced 10 feet apart, cast bold, inky shadows onto the dirt hillside, a 2.2-mile memorial loop around the reservoir.

Caplan’s mother, Lia Brody, and his friend, Micah Woods, came up with the list of names to be memorialized. Six to eight hours of online research by each of them netted about 250 names, said Woods, who is African American.

“Sadly, there’s just so much information about this online,” he said. “But so little has been done to address it.”

They used the Guardian archive “The Counted” — which lists individuals killed by police in the U.S. in 2015 and 2016 — as their primary resource, as well as the site mappingpoliceviolence.org.

“We chose unarmed black Americans and sifted through each case,” Woods said. “99% of the time they were wrongly shot, the wrong person. Some were shot 18 times. How can you justify that?”

Caplan, Woods and Brody sent out texts, Instagram notices and an email calling for project participants last week. They instructed people to meet at Silver Lake’s Neighborhood Nursery School between noon and sundown Friday, and to bring brightly colored fabric, scissors, water and sunscreen. They advised participants to wear masks and keep social distance while working.

Caplan’s brother, Simon, marked up the fence on Friday morning, dividing it into equally spaced-out blocks. Organizers dispersed the victims’ names, along with a sentence or two about how each person died, to participants.

Caplan said they didn’t include back stories on the fence, but adding laminated bios beside each name would likely be the next step. “It’s important to recognize that each of these names is a person with family and friends, who had aspirations. There was a life to them.”

Some participants, however, said they appreciated the project’s minimalism.

“This is just simple and clear and poignant, there’s no confusion,” said Mark Ramos Nishita, a.k.a. Money Mark from his days as a Beastie Boys collaborator. “The expression is pure.”

Nishita, who lives nearby in Atwater Village, was filling in a hollowed-out heart with sheer, ruby red fabric. “It looks like a bleeding heart,” he added.

South Pasadena resident Stacey Mann, who collaborated with Nishita and friends Kim Davis-Wagner and Seven McDonald on multiple names in the installation, said the project felt especially accessible to her.

“I’m a recent single mom — I have two kids — and I have to be very careful about COVID. So I haven’t been out protesting,” said Mann. “But this felt like something I could do, something I could participate in at a distance.”

Mann was working with a vintage floral tablecloth from the ‘50s that she’d cut up. She said she takes the title of the artwork seriously. “As people have walked by, we’ve been asking them: ‘Please say their names, say their names out loud.’”

McDonald, a producer, writer and political consultant who contributed wax cloth fabric she brought back from a trip to Africa, said the victims’ back stories were important to her, so she noted them on her Instagram account.

“Unarmed & bi-polar,” she wrote of Tanner. “There were children in the house, Corey had a 3 month old baby (Flagler County, Florida).”

Reading the stories, McDonald added, “allows me to slow down and feel the infuriating severity of this ceaseless systemic problem.”

“We only make up 13% of the population,” project participant Charlotte W. Langley said of black people in the U.S. Looking at the prevalence of African Americans among the victims of police killings, “it’s undeniable that we have a problem.”

Langley, a TV writer, drew the name “Michael Dean” onto the fence with a crimson red bed sheet, a peace sign beside it. She hoped the project adds perspective.

“There’s no way not to see all these names when you’re walking,” she said. “And in the big picture, it’s impossible to move forward in life with your eyes closed, so we’re opening eyes.”

Project organizers will be holding a candlelight vigil for George Floyd at 7:45 p.m. Sunday at the reservoir. It will start at the intersection of Armstrong Avenue and Lake View Terrace.

Woods said that when he was researching the police killings, “nine times out of 10 the person’s name wasn’t even mentioned until five paragraphs down.”

“It’s so important,” he said, “that we remember that everyone deserves to live, and deserves to be remembered, and have people speak their names: ‘This was Zikarious Flint. This was Alteria Woods. This was Arthur McAfee Jr.’”

Protests continued Monday in L.A. as people take to the streets to protest the police killings of George Floyd and other black Americans.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.