Hollywood Bowl season canceled for the first time in 98 years. So long, L.A. summer

For the first time in its nearly 100-year history, the Hollywood Bowl is canceling its entire season — a loss that amounts to far more than opening night with Brandi Carlile, the film screenings and sing-alongs, the concerts starring Diana Ross, Yuja Wang and Janelle Monáe that were to have followed.

The Hollywood Bowl is summer in Los Angeles. It is running, dizzy, down Highland Avenue with friends after a drink at the Frolic Room or a chilled martini at Musso & Frank.

It is barefoot and tanned just outside the gate, wearing a favorite cotton skirt, the scent of sizzling bacon-wrapped hot dogs and street corn slathered in mayonnaise blending with shouts of “tacos, tortas, aguas frescas!”

It is laughing in the $1 seats at the very top of the amphitheater, the sun melting like deep-yellow butter over the hills, stars blinking awake in the darkening dome of the sky.

The Hollywood Bowl is music: resplendent strings, cascading guitars, heart-beat drums. Classical, rock, jazz, funk, reggae, electronic. Blues, country, gospel, pop, punk. Hip-hop, metal, a cappella.

The shows have never stopped for more than two weeks during the last 100 summers at the Bowl.

The cancellation of the 2020 Hollywood Bowl season comes with more painful news: layoffs of seasonal workers and furloughs for more L.A. Phil staff.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic Assn., which manages the venue, announced on Wednesday the impossibility of attempting a summer season with the coronavirus crisis not yet resolved. The cancellation adds to the mounting revenue losses for the L.A. Phil, which faces an $80 million budget shortfall and will furlough 25% of its non-union workforce and the entire Hollywood Bowl Orchestra. Seasonal employees at the Bowl have been laid off.

“It’s a devastating blow to our organization,” L.A. Phil Chief Executive Chad Smith said in an interview. “As much as we had tried to avoid furloughs for full-time staff up to this point, today that became impossible.”

The reality of a Hollywood Bowl gone quiet for the whole season — a silent summer — is hard to fathom when music played on during the end of one world war and throughout another, through Korea and Vietnam, though the Great Depression and the Great Recession, through 9/11 and all the floods, fires, riots and chaos in between.

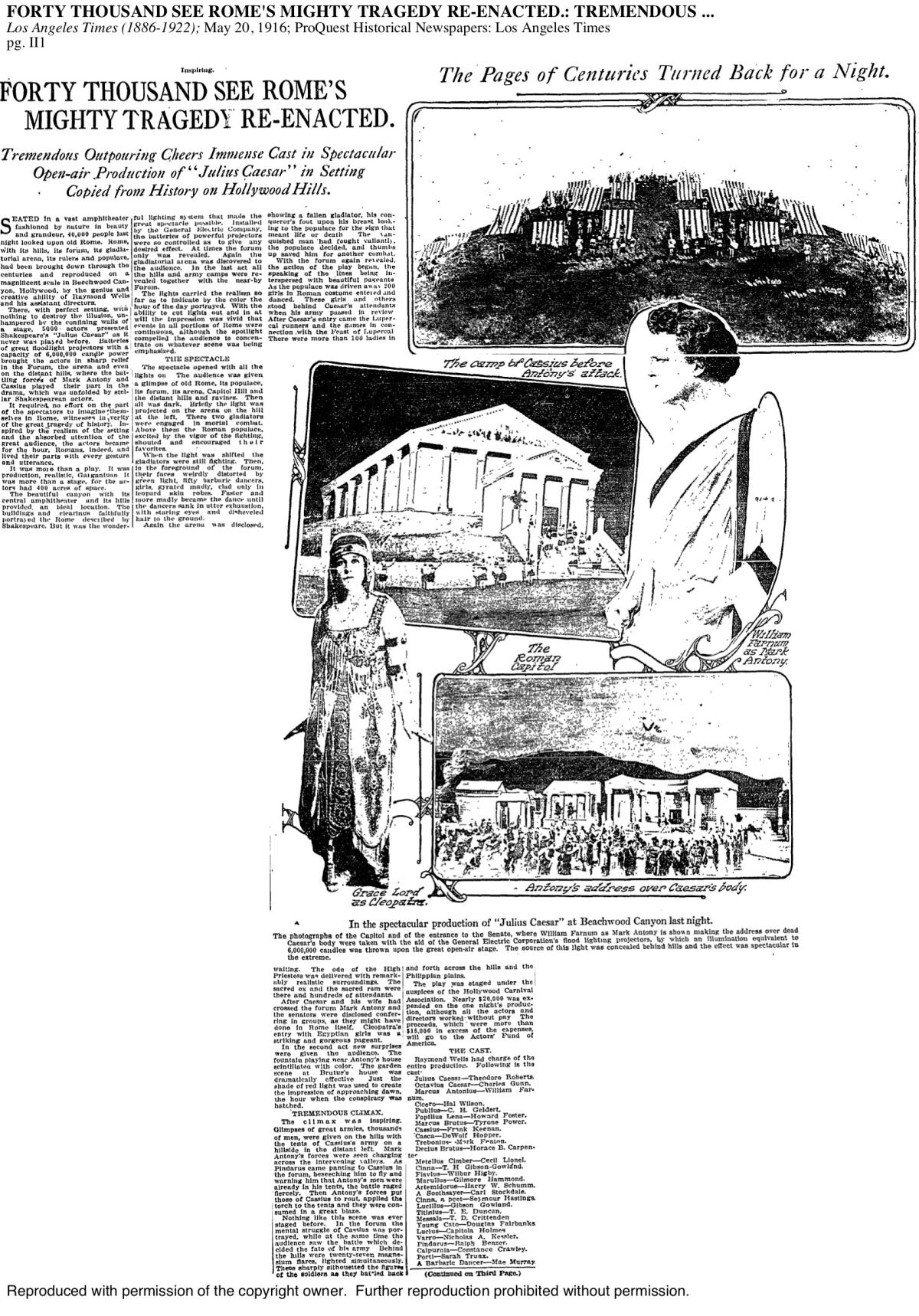

The Bowl first attracted a crowd in 1916 when spectators gathered for a community theater performance of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar.”

It was front-page news in the Los Angeles Times, which chronicled the scene: “Seated in a vast amphitheater fashioned by nature in beauty and grandeur, 40,000 people last night looked upon old Rome … reproduced on a magnificent scale in Beechwood Canyon, Hollywood.”

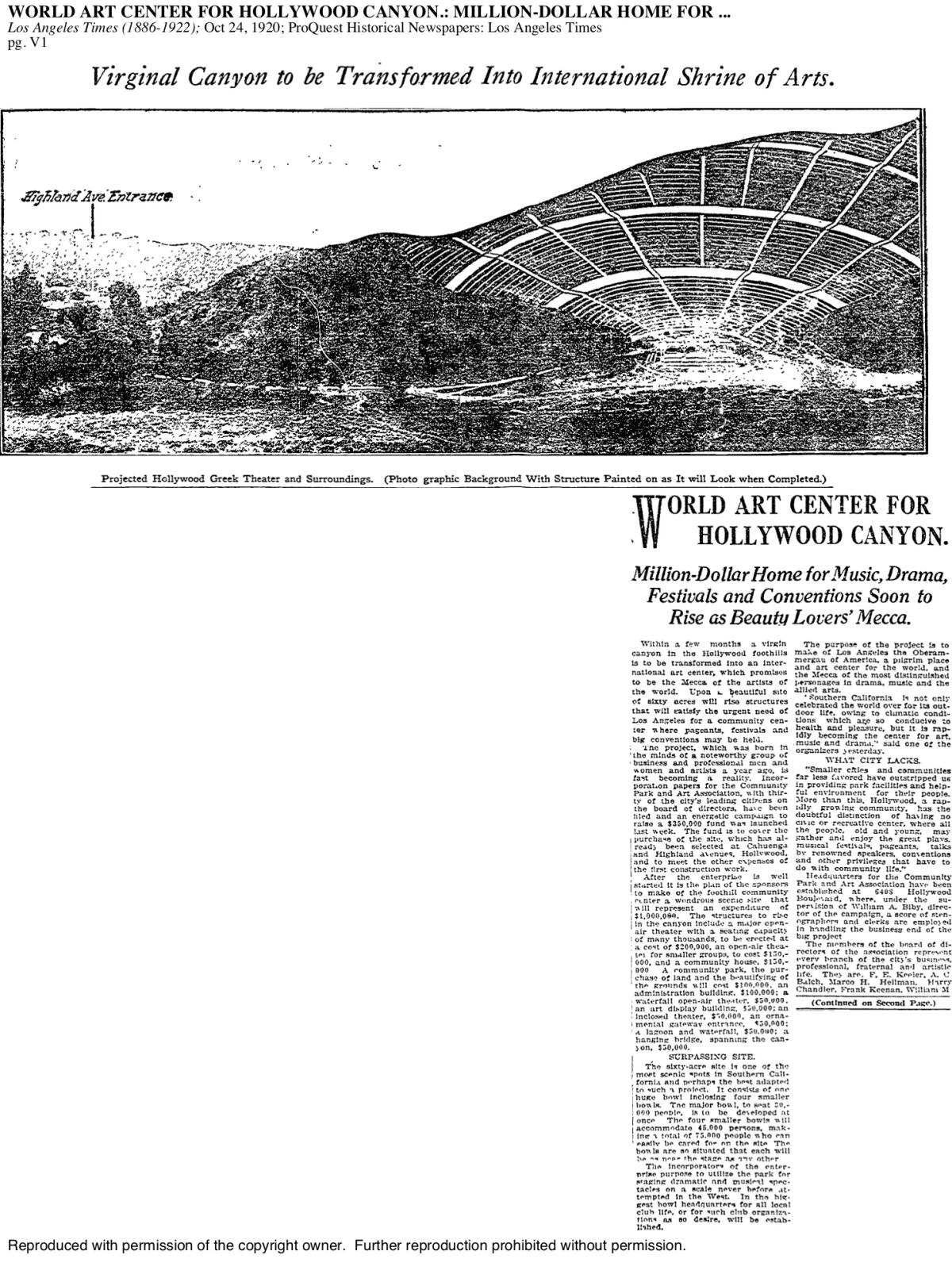

And then four years later, in another front-page dispatch featuring a spectacular rendering of a shining Greek-style theater with coliseum seating:

“Within a few months a virgin canyon in the Hollywood foothills is to be transformed into an international art center, which promises to be the Mecca of the artists of the world. Upon a beautiful site of sixty acres will rise structures that will satisfy the urgent need of Los Angeles for a community center where pageants, festivals and big conventions may be held.”

The Bowl officially opened in 1922 and provided needed entertainment throughout the Depression and immediately afterward: a ballet to celebrate the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, the debut of violinist Jascha Heifetz, a solo recital by pioneering African American tenor and composer Roland Hayes, a memorial service for George Gershwin and the arrival of jazz at the Bowl with Benny Goodman.

In 1942, Bowl crowds were limited to 5,000 people after Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson restricted the size of gatherings on the West Coast, citing war-related safety concerns. When the order lifted late that year, the Bowl was still limited to 10,000 people because of its “location on a main highway which might be needed in an emergency,” according to a Times article.

As the war dragged on, the Bowl found itself in a financial emergency. Concerts weren’t drawing crowds sufficient to sustain it. A show featuring Frank Sinatra — the first pop star to perform with the L.A. Phil at the Bowl — was organized as a benefit to help swell coffers.

A Times article on the upcoming event wasn’t particularly optimistic: “For reasons of war, gasoline shortage, taxes and general apathy, this noble western effort to maintain an art vital to the community may fail.”

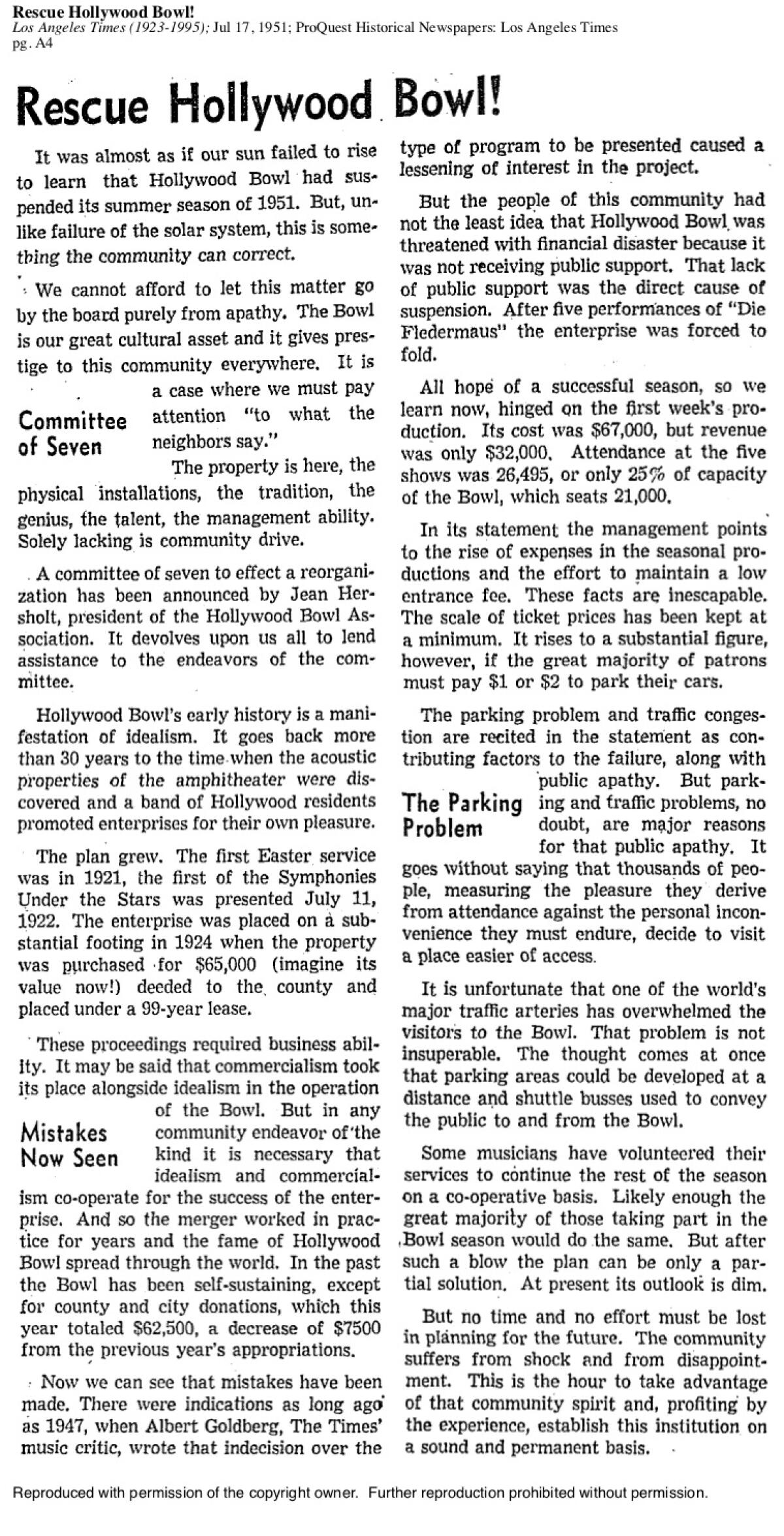

In summer 1951 the Bowl closed temporarily after the season opener — a five-night performance of Johann Strauss’ “Die Fledermaus” — bombed so badly that the Bowl could not afford to remain open. According to a Times article published on July 17 of that year, the production cost $67,000 to stage and earned only $32,000. Attendance was only about 25% of the Bowl’s 21,000-seat capacity.

“It was almost as if your sun failed to rise to learn that Hollywood Bowl has suspended its summer season of 1951,” the article opened. “But, unlike failure of the solar system, this is something the community can correct.”

The Bowl remained dark for less than two weeks while civic leaders and private citizens rallied around an emergency fund that raised more than $80,000. Discussions about how to avoid budget shortfalls ensued, and three new board members included Dorothy Buffum Chandler, wife of Times publisher Norman Chandler and the woman who would later be the driving force of the Music Center downtown.

Deborah Borda, now head of the New York Philharmonic, talks leadership in the coronavirus crisis. Her strategy: Invest in a future that people want.

The following year brought the arrival of the Hollywood Freeway and the ambient traffic noise that would become as much a part of the Bowl’s atmosphere as the roar of applause. Peggy Lee, Nat King Cole, George Solti and Van Cliburn all made their Bowl debuts that decade. Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Art Tatum and the Oscar Peterson trio performed a sold-out show and provided the first documented jazz recording at the Bowl.

Zubin Mehta and moving sidewalks transported audiences in the 1960s, as did the fomenting rock ’n’ roll revolution: the Beatles, Bob Dylan, the Beach Boys, the Who, the Doors, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, the Rolling Stones, Sly and the Family Stone and Carlos Santana.

“The Beatles came, conquered, and left with $58,000 after 30 minutes at the Hollywood Bowl,” wrote Times gossip columnist Hedda Hopper with her characteristic dry panache. “I can’t say I heard them, but with the aid of binoculars I saw them. They’re sweet. … The girls went mad, but it was a harmless madness, screaming their joy in defiance of parents who won’t let them yell at home.”

The 1970s got trippy with a wild mix of the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Luciano Pavarotti, a “Star Wars” show with lasers and Wookiees, the debuts of John Williams and Yo-Yo Ma (both of whom remain Bowl mainstays) and a triumphant performance by Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Frank Gehry added a hatch shell to the Bowl in 1980, suspending hollow fiberglass spheres above the stage so musicians could better hear one another. The decade also would see Ray Charles and Esa-Pekka Salonen, Joshua Bell and Lou Rawls, the celebration of the Summer Olympics in the city.

The 1990s ushered in the launch of the popular Mariachi USA Festival, the founding of KCRW’s World Music series, the establishment of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and quite a bit more of then-L.A. Phil music director Salonen.

“At 35, he has become a figurehead of new-wave culture in an old-wave environment,” wrote Times critic Martin Bernheimer in 1993.

The new millennium brought new life: Beck, Grace Jones and a 24-year-old conductor from Venezuela named Gustavo Dudamel.

The talent onstage has changed but the audience’s relationship with the Bowl has remained constant — one year stretching into the next, until the parade of time can be marked by shared moments in this place.

Birthdays, first dates, marriage proposals, reunions with dear friends. Picnic baskets laden with soft cheese, crispy bread and farmers market greens. The juice of ripe summer fruit dripping down chins. Splurging on a box seat and flagging down a server for another bottle of chilled Champagne.

Memories of the summer the wife seemed like she might go into labor during the Fourth of July fireworks celebration. The first time the daughter came along, wriggling and giggling with joy during a live sing-along of “The Little Mermaid.”

The loss of all that will hurt just as much as the concert cancellations of highly anticipated shows: Dudamel’s new Pan-American music initiative as well as his conducting of Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana” with the Los Angeles Master Chorale and the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus. Cynthia Erivo, Andrew Bird, Flying Lotus, Brittany Howard. An evening celebrating the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which prohibits the denial of voting rights on the basis of sex, and the suffragettes who fought for it.

With this season gone, there is always next summer and a possible headline: “Hollywood Bowl roars back to life in a blaze of fireworks and moonlight.”

The lede: “Crowds packed tightly together, children ran through the grass, friends shared wine and music. It was again summer in Los Angeles.”

Beong-Soo Kim and Bonnie Wongtrakool play cello and piano every weekend. For neighbors in lockdown, the music provides an escape, if only for an hour.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.