L.A.’s theater community pays tribute to its ultimate fan, Kerry English

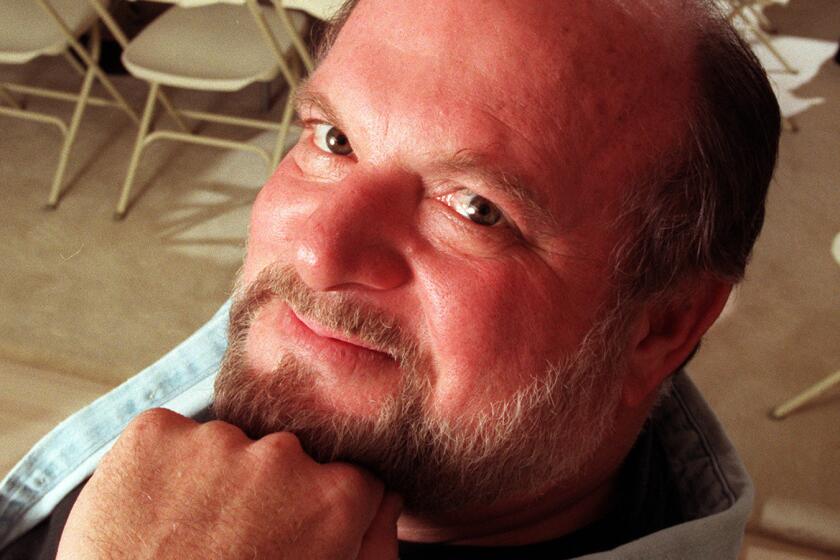

Actors peeking from the stage wings could reliably spot Kerry English: dapper older gentleman, kind, interested smile, platinum white hair and matching goatee. His reassuring presence was never a surprise; only his absence was.

English, a respected pediatrician who took a special interest in caring for at-risk children, was as much a part of the Los Angeles theater scene as the actors, directors, stagehands and designers, those who knew him said.

He was the ultimate theater fan, a cultural omnivore who sometimes took in more than five shows in a week. He was a devoted audience member who became a reliable board member at theaters including Rogue Machine, Cornerstone Theater Company, Ojai Playwrights Conference and 24th Street Theater.

English died Tuesday of complications from ALS. He was 74. The news spread quickly among L.A. theater lovers and practitioners. Tributes flooded message boards and social media, and stories were shared via email and over the phone.

The death of someone so intimately connected to the local arts community felt all the more tragic at a time when coronavirus has torn that community asunder, leaving those accustomed to uniting in the name of creation alone in their homes to grieve.

“It would have a tremendous sting no matter what,” said John Perrin Flynn, artistic director of Rogue Machine. “But it has more of a sting right now, when we’re all facing an uncertain future.”

English, who was the longtime director of the pediatric division at Martin Luther King Jr. Hospital in L.A., represented a steady love for the art form, said those who knew him. He was discerning, he knew what made a show good and when it needed work, but he was never quick to criticize, instead choosing to focus on the positive.

“It was just so thrilling to meet a human being whose idea of a good time was to just go see many, many plays,” said Boston Court Pasadena’s artistic director, Jessica Kubzansky, adding that she saw English at practically every show she attended, from the smallest 40-seat house to productions at the Mark Taper Forum in downtown L.A. or South Coast Repertory in Orange County. “As theater professionals we run into each other all the time, but to run into a professional audience member is a particular joy.”

English’s wife, Olga Garay-English, said Kerry’s love of theater could be traced back to the early 1970s when he saw “Cyrano de Bergerac” starring Richard Chamberlain at the Ahmanson Theatre. There were three curtain calls and the house exploded with enthusiasm.

The experience, she said, awakened Kerry to the “power of theater to illuminate the world.”

Garay-English served for nearly seven years as executive director of the L.A. Department of Cultural Affairs, and the pair were perfectly matched in their love for — and involvement with — the arts, she said.

They were married in 2011 by then-Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, in front of the fountain at the Music Center, with a reception upstairs at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

English loved every aspect of theater, including postshow talk-backs, workshops and table reads. He loved speaking with the actors, and he relished getting to know the stagehands, Garay-English said. He had a particular fondness for Greek theater, and his wife said she regrets that in their many international trips to see theater, they never found their way to Greece.

Garay-English said she remembered times when her husband would see up to three shows in a day — a 2 p.m., a 5 p.m. and an 8 p.m. And if they attended a festival, it wasn’t unusual for him to be in the audience of more than a dozen shows in a week.

“He was as fully engaged in the last one as he was in the first one,” she said.

Robert Egan, artistic director of the Ojai Playwrights Conference, said he first came to know English in the 1980s when Egan was recruited as the producing artistic director for the Taper, tasked with reviving the legacy of new-play development that had been the hallmark of the place.

Egan was overseeing 16 new-play events at various locales across the city, and at every single one of them he’d spot a guy with a goatee and elegant silver hair who had “this intense gaze, like he really wanted to interact.”

That man was English, and he would later become a great friend to Egan, who loved him for “always squeezing the human soulful essence out of a theatrical experience.”

This is why Egan and others think that English, a doctor with expertise in trauma (he testified as a sexual-abuse expert during the McMartin preschool trial in the 1980s), found such a deep connection to theater.

“I think he really loved how theater revealed human behavior, and what human beings are capable of,” said Bill Rauch, former artistic director for Cornerstone as well as Oregon Shakespeare Festival and currently artistic director for the Ronald O. Perelman Performing Arts Center, being built in the World Trade Center. “Whether it was his medical practice or his theatergoing, Kerry had a love of people and believed each individual human story had value.”

Peter H. Hunt followed his success of ‘1776’ with a long film and TV career, plus a decade as artistic director of the Williamstown Theatre Festival.

It wasn’t just the final production that fascinated English, Rauch said. Every aspect of the work, down to the most minute detail of creating a show, held sway.

Veralyn Jones, an actress and co-associate producer for Lower Depth Theatre, said English always came across as much more than just a fan.

“He wasn’t just someone who showed up at your shows, he was someone who invested in you as an artist,” she recalled.

Jones remembers a time when she was scheduled to do a reading of “Medea” at Antaeus Theatre Company, and English wrote to her early in the day to let her know that he was on a plane but that he would race to the theater as soon as he landed.

The theater represented community to English. He came to know everyone. He became a dear friend to Jones and a grandfather-like figure to Jones’ now-21-year-old daughter. When she was little, he’d take her to shows with his own grandkids, hoping to pass along a love of the art to the next generation, Jones said.

When English became sick with ALS, the theater community soon became aware of the diagnosis and of the perils of a disease that is still without a cure.

English was “beautifully Brechtian, beautifully Chekhovian — both in the same person” about his illness, Egan said.

Before his death, plans were in the works to honor English while he was alive. A performance was going to take place at Rogue Machine, Flynn said, and it would have featured scenes from plays that held special meaning for English.

Coronavirus put those plans on hold, and now the show will no longer happen with English in the audience, as he had always been.

“We were looking forward to doing that when at last we could gather again,” Flynn said. “And we’ll still probably try to do something, but it won’t be the same.”

Move productions outdoors? Present different work? Faced with so many unknowns, one artistic director vows: “We all will sit in a theater again.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.