Commentary: President Trump vs. Oedipus Rex: Leaders reveal themselves in times of plague

Tragedy isn’t Donald Trump’s natural habitat. As a protagonist, he’s bursting with hubris but woefully short on gravitas. His grandiose personality defects — the blustering, mendacity and truculent solipsism — are made for “South Park,” not Sophocles.

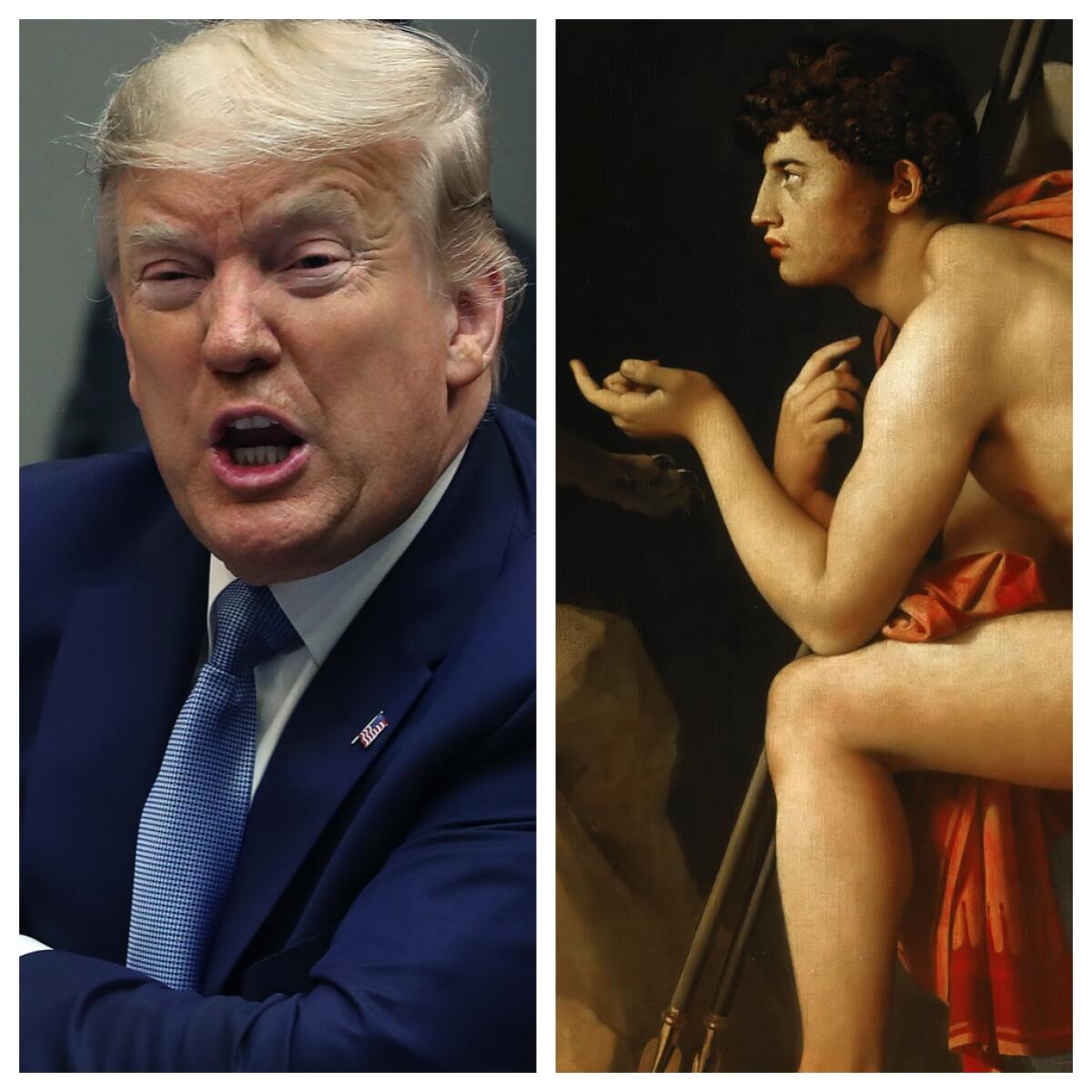

Yet watching Trump perform his carnival barker act on the podium at the daily White House briefings on the coronavirus crisis, I am stuck by the parallel between our president and that quintessential Sophoclean sufferer, Oedipus.

No, I’m not making any innuendos about Trump’s unconscious desires. Freud elaborated a theory of psychoanalysis from Sophocles’ play “Oedipus Rex,” extrapolating from the myth a stage in psychosexual development in which a boy secretly longs to supplant his father in his mother’s affections.

The ancient Greek tragedians had bigger fish to fry than the origins of male neurosis. Sophocles’ tragedy, held up by Aristotle as a model of structural elegance, probes the deepest existential questions. To read the play, to follow Oedipus’ trajectory from first of men to accursed outcast, is to confront the paradox of humanity’s breathtaking majesty and inescapable frailty.

But “Oedipus Rex” is also a study in political leadership. The play explores the relationship between good governance and humility. Oedipus, the Theban ruler, confronts a plague that’s killing the crops and causing widespread sterility. Death and destruction are closing in. A priest flocked by suppliant children entreats Oedipus, renowned for his mental prowess, to find the answer that will rescue the city.

No one could fault Oedipus’ response. Unlike Trump, he doesn’t pretend that the blight is a partisan hoax or an overblown media story that will one day magically disappear. “I pity you children,” Oedipus says after the priest makes his plea. As sovereign, he bears the weight not just of his individual sorrow but of the sorrow of each of his subjects:

“My spirit groans

for city and myself and you at once.

You have not roused me like a man from sleep;

know that I have given many tears to this,

gone many ways wandering in thought …”

Oedipus has flaws, but a lack of empathy isn’t one of them. There’s also no shirking of duty or deflecting of responsibility. After learning from his brother-in-law, Creon, who has just returned from Apollo’s temple, that the plague is the result of the still unsolved murder of the previous king, Laius, Oedipus vows to do everything in his power to identify and expunge the culprit. He issues orders to his people and invokes a curse on the guilty party, never imagining that he’s hastening his own doom by proceeding with such urgency.

The contrast with Trump is initially stark, but political pressures draw out points of comparison. When Teiresias, an old blind prophet, reveals under duress that the murderer is in fact Oedipus himself, the king, not knowing his true origins, reacts as though he’s the target of a political hit job. He imagines that the seer is in cahoots with Creon, who must be scheming to overthrow him.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles lays off gallery attendants, exhibition installers and educators, among others.

Insulted and incensed, Oedipus responds as intemperately as Trump when crossed by a politician or held to account by a member of the press. To salve his injured pride, Oedipus harks back to the equivalent of his electoral coup. It was through the sharpness of his wit that he, an outsider not in the royal line of succession, solved the riddle of the Sphinx and won the throne.

The title “Oedipus Tyrannos” is often preferred by translators to “Oedipus the King” or “Oedipus Rex,” as the Greek word calls attention to the way power was obtained through achievement rather than heredity. It also retains for us the sense of “tyrant,” an ever-present danger when a ruler convinces himself that his authority is unimpeachable.

“Insolence breeds the tyrant,” the chorus intones, as Oedipus’ temper grows more combustible as Teiresias’ once-unthinkable prediction becomes increasingly plausible. Jocasta tries to reassure her husband that oracles don’t always get it right by telling him that one once told Laius that he would die by his son’s hand. How crazy was that! She’s willing to pooh-pooh religious principle to assuage Oedipus’ anxiety, but nothing can stop the past from remorselessly revealing itself.

A tragedy as ruthless as “Oedipus Rex” cannot be domesticated by moralizing bromides. Sophocles didn’t dramatize his version of the myth so that we could connect the character’s catastrophic fall to a personal shortcoming. There’s nothing in the play to suggest that Oedipus could have outrun the prophecy that he would one day murder his father and sleep with his mother. His leadership style may be choleric, but that is not what caused him to fulfill his horrific fate.

Ironically — and Sophocles’ play is built on structures of irony — Oedipus discovers his guilt through his merit. His dogged sense of responsibility and brilliance propel him to unearth the truth of his identity.

In his essay “On Misunderstanding the Oedipus Rex,” E.R. Dodds dismantles the notion that Oedipus must be either a victim of fate or a casualty of his own faulty character. While Dodds accepts that “Oedipus Rex” is “a play about the blindness of man and the desperate insecurity of the human condition,” he insists that it is also a work “about human greatness.”

How exactly is Oedipus great? “Not in virtue of a great worldly position — for his worldly position is an illusion which will vanish like a dream — but in virtue of his inner strength: strength to pursue the truth at whatever personal cost, and strength to accept and endure it when found.”

Terrence McNally, perhaps the most important comic voice in theater since Neil Simon, wrote to amuse and awaken. Humor was his shield but also a bridge. He taught his characters to connect. And audiences.

Oedipus’ distinction lies not so much in the profundity of his suffering as in the heroism with which he accepts responsibility for crimes he was subjectively innocent in committing. As a man he is fallible and all too human. But his commitment to the truth and to public duty, while unable to spare him his cruel destiny, ennobles him and, by extension, all of mankind.

Donald Trump is no Oedipus. His loyalty ends with himself and his narrow political interests. I’m not sure Sophocles would know what to do with a reality TV president, but imagining the prospect is useful.

What separates Sophocles from his ancient Greek rivals, Aeschylus and Euripides, is his genius for character drawing. Sophocles’ sculptural approach to dramatic poetry allows us to take in the larger pattern of a life even as details of the composition impress upon us the individuality of the figure.

There’s such tumult around Trump, much of it self-created, that the media impression is a blur of noise.

Aristophanes would have fiendish fun whisking our dear leader off to some imaginary circus world. But Sophocles encourages us to stand back and view the human outline against the societal backdrop. Yes, even a raging tyrannos can tell us about our vulnerable humanity.

As the world confronts a new pandemic, it behooves us to consider why the cornerstone text of Western literature is a play about a ruler discovering himself while confronting a plague. Nothing cuts our species down to size quite like a scourge. The fragility of our condition and the illusory nature of our achievements are instantly thrown into relief.

At the same time, there is an opportunity to transcend our limitations through the acceptance of our helplessness — to gain strength by acknowledging weakness. Leaders demonstrate courage when they submit to truths more powerful than themselves. Unfortunately, the last thing Trump wishes to be is a tragic hero, and that right now is our collective tragedy.

Organizers of the 74th Ojai Music Festival, scheduled for June, pull the plug. They cite travel uncertainty and the safety of artists and audiences.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.