Matthew Lopez: Terrence McNally showed the gay community a vision of life with dignity

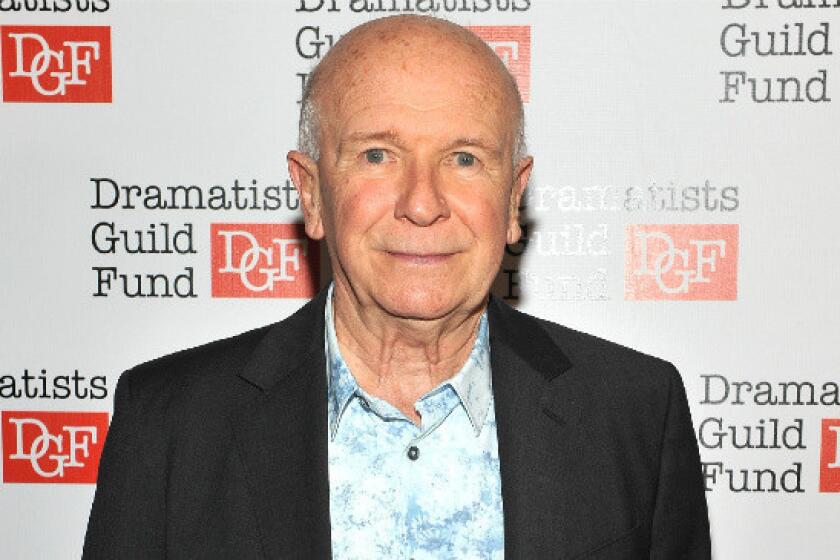

Terrence McNally died on Tuesday from complications related to the novel coronavirus. Matthew Lopez, the playwright behind “The Inheritance” and “The Legend of Georgia McBride,” spoke to The Times through tears from upstate New York, paying tribute to the theater giant in this edited remembrance, as told to Times staff writer Ashley Lee.

I first accessed Terrence by watching the Tonys in the ’90s, when it basically just became an annual tradition to give Terrence a Tony Award, between “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” “Love! Valour! Compassion!” “Master Class” and “Ragtime.” I remember the year that “Love! Valour! Compassion!” won — I was not yet out but just starting to understand that I was gay. That play was important to me without actually realizing why. Even though there really wasn’t any character that resembled me or my life, it didn’t matter because I found a common humanity with them. Terrence’s writing helped me be OK with being gay, it comforted me. He reached out and he spoke to me.

Growing up in the ’80s and ’90s and in the very conservative panhandle of Florida — an area of the country that was really hostile to the queer community — there wasn’t a lot of comforting voices for young queer kids, but Terrence was one of them for me. He was the first writer to show me there was more to being a gay man than dying of AIDS, that there was more to being a gay man than living tragically and dying tragically. Terrence taught me that it’s possible to live a life filled with dignity as a gay man. That was his great gift not just to the queer community but to all of humanity.

The one thing no one ever got about “The Inheritance” was that I wasn’t chasing Tony Kushner, I was chasing Terrence. Terrence was the spiritual godfather of that play. None of the critics, whether praising or critiquing the play, ever saw it. But Terrence did. And that made me incredibly proud.

Terrence McNally, whose varied and prolific career as a playwright, musical librettist and screenwriter earned him five Tony Awards and an Emmy, died Tuesday.

I do not exaggerate when I say I wouldn’t be a writer today if Terrence McNally hadn’t encouraged me to write. When I moved to New York, I sent out a bunch of letters to different people in theater, asking for work and advice. Hal Prince suggested I reach out to Terrence, who invited me to assist him in a workshop of the musical “A Man of No Importance.”

It was so clear that Terrence had no need of an assistant whatsoever, and the reason he was doing it was because I asked. That was Terrence. He encouraged questions and would ask me things too: Do you see why we’re cutting that line? Do you understand that decision we just made? He encouraged questions. It was like a two-week master class; my job really was to watch, observe and learn.

In exchange for the “work” that I did for him, he read one of my plays. I remember telling him I wasn’t sure if I was a writer or not, and I just needed someone’s opinion. About a week after I sent something to him, I got a very long, very detailed voicemail from him in which he praised my work, critiqued my work, challenged my work and encouraged me. He ended the voicemail with, “I can assure you that you are a writer, and you need to keep writing.”

I doubt Terrence would’ve ever said, “You’re terrible, go into another line of work, you should really think about dental school” — and if he did, I probably would be a dentist to this day — but it was the encouragement that I needed. That piece of writing turned into “The Whipping Man,” the play that started my career. He was at the opening night. I remember asking him if he remembered reading that, and he goes, “Absolutely. Why do you think I’m here?”

Terrence was always so lovingly blunt. “This is really interesting; this, I have no use for.” I’m sure his honesty cuts both ways, but you always knew where you stood with him and you could always trust him, as a person and an artist. He would never lie to his audience. And it was because he was so honest and trustworthy as a storyteller that you believed him. He really could bring you as an audience to places that you never would’ve expected to go at the beginning of a particular story.

More than any other playwright of his generation, he had the ability to look honestly at the world and not ignore its flaws but to actually see the beauty in the flaws. Terrence never ever sugarcoated anything, and yet, because of who he was as a person and a writer, he was able to find a tremendous beauty in the unlikeliest of places. I think that will be his great legacy.

The theater community is mourning Terrence McNally, the 81-year-old Tony-winning playwright who died Tuesday from complications related to the coronavirus.

If anybody who’s not familiar with the work of Terrence McNally is wondering why his death matters, it’s because his whole life and his work was in service of moments just like these. And while I am heartbroken today, I’m also so grateful that he left behind a mountain of work that speaks to the very time that we live in. It’s a reminder to us that when we are eventually on the other side of this horrible, horrible experience that all of the world is going through right now, we will remember to find beauty.

He taught us how to be human in the face of heartbreak, how to find compassion for one another and for ourselves. He gave us a road map for how to be a survivor and how to honor those we lost. Terrence taught us, through his writing, how to remember him and how to mourn him. And we can extrapolate that not just for Terrence’s life but to the lives of all of those who are being lost right now.

In the last lines of “The Inheritance,” Henry says to Walter, “What do I do now, Walter? Tell me what to do.” And Walter says, “You do what they could not — you live.” I think, in some ways, those lines are the summation of the lessons that I’ve learned from Terrence — as a gay man, as a dramatist, as a human being.

Terrence McNally, perhaps the most important comic voice in theater since Neil Simon, wrote to amuse and awaken. Humor was his shield but also a bridge. He taught his characters to connect. And audiences.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.