Commentary: As Center Theatre Group sputters, L.A. struggles to realize its artistic potential

The cultural balance of power between Los Angeles and New York has shifted to the West in the eyes of a growing number of artists and aficionados with an intimate knowledge of both coasts. Ask any painter, composer, critic or connoisseur who has fled the mallification of Manhattan and discovered the riches of L.A.’ s classical music, opera and visual arts scenes and you’ll hear testimony from a convert.

Rarely, to my chagrin, is our local theater part of the conversation. Los Angeles is undeniably a theater town. Important works are launched from our stages before traveling the nation. The city receives the pick of touring companies. Small venues, such as the Fountain Theatre and Echo Theater Company, punch well above their weights. Still, something is missing.

What is the distinctive stamp of L.A. theater? In posing this question to myself, I find my answer to be dismayingly similar to what I would have said when I moved to Los Angeles from New York 14 years ago to be The Times’ theater critic. The theater has remained decentralized, widely variable in quality and ambition, and sorely in need of institutional leadership able to meet the self-regard of a city that, long out of New York’s shadow, has come to recognize itself as a global metropolis.

One organization plays a disproportionate role in L.A.’s theater fortunes. Center Theatre Group, comprising the Ahmanson Theatre and the Mark Taper Forum at the downtown Music Center and the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City, is as dominant in its institutional presence as the Los Angeles Philharmonic, except no one these days would make the comparison. Whereas the L.A. Phil has become the leading classical orchestra in America with its innovative programming, educational outreach and devoted following, CTG has been struggling to lift itself out of survival mode, succeeding brilliantly on occasion, only to fall back into timidity and torpor.

I arrived at The Times not long into Michael Ritchie’s tenure as artistic director of Center Theatre Group. Ritchie, who took over from Taper founder Gordon Davidson, has had a tough road. First, he had to step into the outsize shoes of an artistic director who single-handedly put Los Angeles theater on the map with landmark productions of “The Shadow Box,” “Zoot Suit,” “Children of a Lesser God,” “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992,” “Angels in America” and “The Kentucky Cycle.” Then Ritchie had to contend with a devastating recession that only exacerbated trends in cultural patronage that placed greater emphasis on box office sales as donors and subscribers became less reliable fixtures of the business plan.

The rebound of the economy hasn’t returned CTG to the good old days. Economic inequality has hollowed out the middle class from which the subscriber pool is drawn. With incomes failing to keep pace with the cost of living, even the relatively affluent are questioning whether to sign up for another grab bag season.

Hastening the spiral is the availability of on-demand entertainment, an especially enticing option in Los Angeles, where the idea of fighting traffic after work and overpaying for parking could turn even the most avid culture vulture into a couch potato. With the long decline in arts education funding, millennials and their screen-glued juniors see little value in following in the footsteps of their subscription-holding grandparents. Why commit to a package of sketchy shows when purchasing single tickets at the last minute, even if dynamic pricing exacts a heavy premium, allows one the freedom to pick and choose?

Ritchie has sharp showman instincts. At his programming best, he combines high production values with buzz-worthy fare. A great share of the work, however, has either originated or been celebrated in New York before it reaches one of his theaters, leaving the impression that the main task of an artistic director is Broadway shopping.

And even this part of the job has been getting more difficult, as top Broadway shows that at one point would have automatically come to the Ahmanson on their national tours are now being shunted off by powerful producers to the Hollywood Pantages. I was grateful to see “Fun Home” and “Dear Evan Hansen” at the Ahmanson, where they belonged among an audience with cultivated dramatic taste. But when the Pantages announced that “The Band’s Visit,” a Tony-winning music drama of moonlit delicacy, would be at the Dolby Theatre as part of the Broadway in Hollywood 2019-20 season, it seemed as if a Rubicon had been crossed.

There’s currently a one-man-show at the Ahmanson, John Leguizamo’s “Latin History for Morons,” with another soon to follow, stand-up comic Mike Birbiglia’s “The New One.” After the strenuous horseplay of this summer’s “The Play That Goes Wrong,” a national tour production that was on virtually no one’s must-see list, it’s easy to understand why musical lovers who have loyally kept up their Ahmanson subscriptions for decades have been emailing me to say they’re finally prepared to let them go.

Hits at the Ahmanson are CTG’s financial lifeblood, so perhaps the increased competition for touring shows explains why the Douglas is often dark and the Taper all too regularly tame. I’m not underestimating the challenges of the current environment, but Ritchie has compounded the difficulties by not shoring up weaknesses in his own leadership.

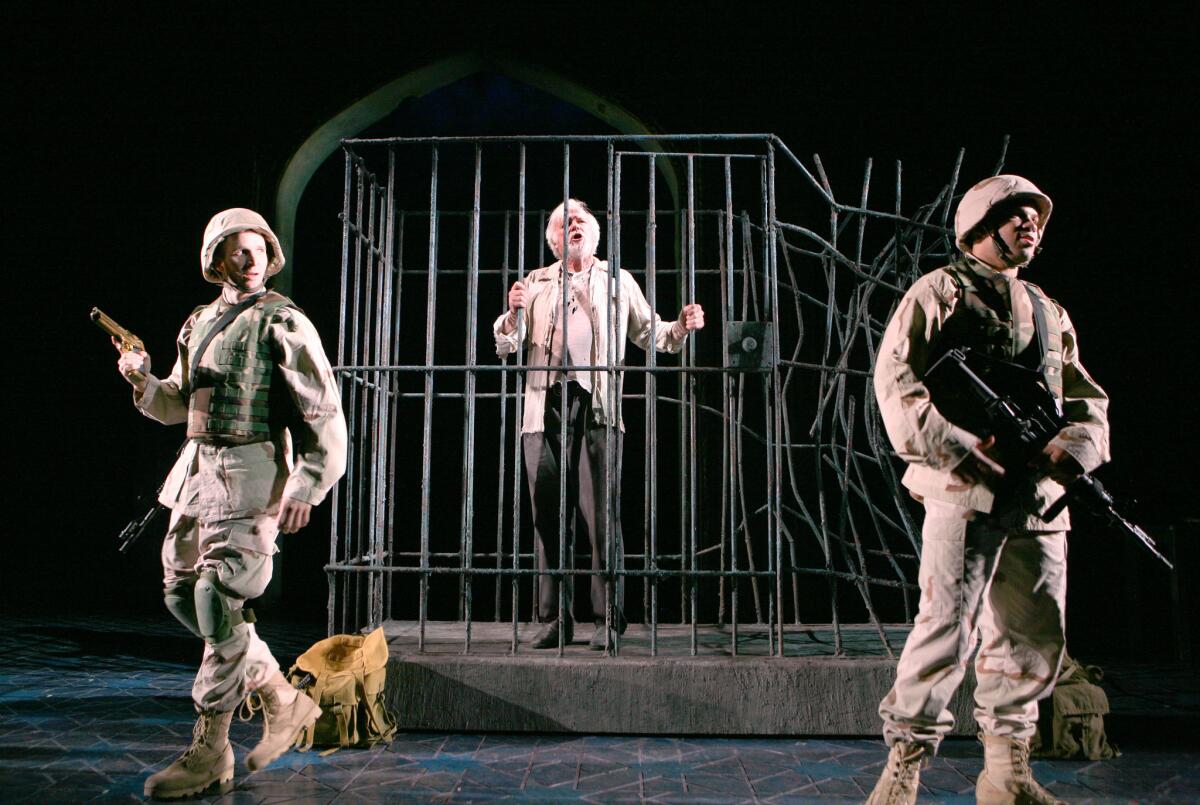

Opportunities have been missed. American playwriting is in the midst of a renaissance, but you’d know little about it from CTG. With a few notable exceptions (Rajiv Joseph’s “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo,” Lucas Hnath’s “Dana H.”), the best of this work hasn’t premiered at the Taper or the Douglas.

More inexplicably, many of the playwrights shaking up the American theater don’t seem to be on Ritchie’s radar. And for those who are, the invitations are frequently late and not for their best work. Annie Baker, a leading figure in this new generation of dramatists, will finally be having her Taper debut in the spring, but not for her Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Flick” (which has yet to be produced in L.A.) but for “The Antipodes,” a transitional play that is not an ideal introduction to this path-breaking talent.

Brad Fleischer, left, Kevin Tighe and Glenn Davis in Rajiv Joseph’s “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo” at Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City in May 2009. It was “electric.”

Delighted as I am that Heidi Schreck’s “What the Constitution Means to Me” will be coming to the Taper in January, I can’t help feeling a twinge of envy that Berkeley Repertory Theatre had the foresight to produce the work before it reached Broadway. (Berkeley Rep also had the vision to co-produce with Soho Rep Jackie Sibblies Drury’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Fairview,” another play still waiting for its L.A. closeup.) The downside of this delay is that Schreck won’t be reprising her unforgettable performance of herself as a high school debate champion, who as a young woman confronts firsthand the thorny constitutional questions about female autonomy she once academically held forth on. Maybe this revised version will be something special, but on paper it sounds comparable to a John Leguizamo show being sent on the road without Leguizamo.

There are counter examples demonstrating Ritchie’s readiness to get in the game early, such as Tracy Letts’ “Linda Vista” (which recently opened on Broadway) and Bruce Norris’ “A Parallelogram” and “Clybourne Park.” But the openness to prickly works by white male authors at the Taper raises questions about the dividing line between mainstream and marginal.

Time and again with less established writers, safer plays have been chosen over more groundbreaking work. Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ “Appropriate” was deemed more fitting for the Taper than his “An Octoroon,” which is widely regarded as one of the most important American dramas of the last decade. Tarell Alvin McCraney’s “The Brother/Sister Plays” announced the entrance of new lyrical voice that Hollywood would discover through the Oscar-winning film “Moonlight.” But it was the Fountain Theatre that expertly produced two of the three plays in “Brother/Sister” trilogy. The Taper opted for McCraney’s “Head of Passes,” a play that was notable chiefly for the powerhouse performance of Phylicia Rashad.

“An Octoroon” would have been ideal for the Douglas, if the Douglas had established itself as a venue for experiment. Young Jean Lee’s “Straight White Men” was produced at the Douglas after its run at New York’s Public Theater but before it reached Broadway. And there have been a few memorable premieres (Jennifer Haley’s “The Nether” springs to mind), but not enough to carve out a distinct identity.

This fall, the only production at the Douglas is Bill Irwin’s “On Beckett,” which came from New York’s Irish Repertory Theatre. Money is no doubt an underlying issue for CTG’s fond step-child. But then why not bring in someone who would be inspired to infuse life into the programming, build the audience and share in the fundraising labor needed to pay for it all?

When talent and timing are brought together at CTG, the results have been world class. The Taper production of Christopher Durang’s Tony-winning “Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike” was superior to the New York staging, thanks to David Hyde Pierce’s impeccable comic direction and the casting of Christine Ebersole in the Masha role that Sigourney Weaver originated. I was grateful to see Sterling K. Brown reprise his performance in Suzan-Lori Parks’ prodigiously daring “Father Comes Home From the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3)” at the Taper.

But productions haven’t always lived up to the writing. The mishandling of Quiara Alegría Hudes’ Pulitzer Prize-winning “Water by the Spoonful” is perhaps the most crushing example. But even non-disastrous stagings, such as Lisa Peterson’s production of Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Sweat,” can underwhelm, leaving audiences to wonder what all the fuss is about.

CTG should be part of the national playwriting conversation as both incubator and coveted showcase of original writing. Developing new plays is time-intensive, expensive and dependent on dramaturgical know-how. The latest Taper botch, a set of one-acts by Ethan Coen inaptly titled “A Play Is a Poem,” once again had me wondering: Who beyond Ritchie is minding the literary store?

When I think of the pointless David Mamet plays CTG has foisted upon us at a time when so many brilliant writers have yet to find the L.A. stage they deserve, I am overcome by a sense of waste. What is driving the decision-making? Convenient relationships? Budgetary fears? Lack of imagination?

“New plays are a hard sell” is an argument I’ve heard. But this prophesy is self-fulfilling for audiences who have been trained to behave as consumers. The rewards of playgoing — emotional enlightenment, intellectual challenge, initiation in an artistic movement — are different from the rewards of fine dining. Marketing is still key, but community building must be the goal.

If playwrights and directors were introduced in their artist contexts the way painters, sculptors and photographers are presented at LACMA or the Hammer Museum, perhaps CTG would be more effective at reaching a broader demographic. Success obviously isn’t guaranteed, but Los Angeles strongly supports innovative work in classical music and the visual arts, so why should theater audiences be assumed to be so staid? Not everyone is after passive consumption.

Local artists complain to me that Ritchie is less inclined to look in his own backyard than to call upon New York talent. Theater is both local and nonlocal, and a proper balance needs to be struck. There’s more going on behind the scenes in terms of commissions and workshops than is apparent in any season brochure. But if the risk management strategy seems to bounce between cautious and crap shoot, it’s symptomatic of a chronic neglect in audience development. As Freud confessed a confusion about what women want, CTG can’t seem to figure out what L.A. theatergoers long to see.

Why can’t the flagship theater organization of the city that calls itself the entertainment capital of world expand its cultural horizons? It certainly makes sense for CTG to continue to take advantage of the enormous pool of playwriting talent that has migrated West during this explosion in television.

“Los Angeles strongly supports innovative work in classical music and the visual arts, so why should theater audiences be assumed to be so staid?”

But I’m thinking back to conversations in the last year I’ve had with artistic leaders, who have expressed a common wish that interdisciplinary performance — work that falls between the genres of dance, opera, theater and visual installation — would be more fully appreciated as the city’s house style. No, they weren’t talking about the annual Matthew Bourne import. They were talking about the future of contemporary performance as glimpsed in Yuval Sharon’s production of “Atlas” and the “junkyard opera” of Four Larks, and they were heartened by the mad embrace of Taylor Mac’s “A 24-Decade History of Popular Music” at the Theatre at Ace Hotel.

Strange that this needs to be said in 2019, but the standard playwright-director formula of regional theater isn’t the be-all and end-all. Work that straddles the various strengths of the Southern California cultural scene ought to be more in evidence in the programming of a theatrical organization that has such a large footprint at the Music Center.

When Lars Jan’s multimedia homage to Joan Didion’s “The White Album” was presented by CAP UCLA at Freud Playhouse in April, I took note that CTG was part of the producing team. In my review, I suggested that the Taper or Douglas should pick up the piece for a longer run, but mainly I wanted to encourage Ritchie to consider the possibility that perhaps there’s more life in niche alternatives than in middlebrow mediocrity.

A radical rethinking of artistic vision requires an openness to the possibilities of new management structures. CTG isn’t thriving as the kingdom of one artistic liege, assisted by a court of associates and answerable ultimately to a board of directors. Diversity isn’t measured solely by how many plays are produced by writers of colors and women but by who has the authority to green-light ideas and shepherd them from the lab to the stage. Expanding the leadership brain trust can open up new artistic frontiers. CTG’s collaboration with East West Players on the David Henry Hwang-Jeanine Tesori musical play “Soft Power” may have had a rocky birth at the Ahmanson, but the ambition and boldness were invigorating. Something new was midwived into existence.

If the ultimate goal for a regional theater these days is a national identity with a self-sustaining business model, there has to be room for the development of a local aesthetic. I return to the question: What is L.A. theater? The city has come too far to accept a diet heavy in New York seconds from its largest nonprofit theater. CTG must, for its own survival, be part of the discovery of what our theater can be.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.