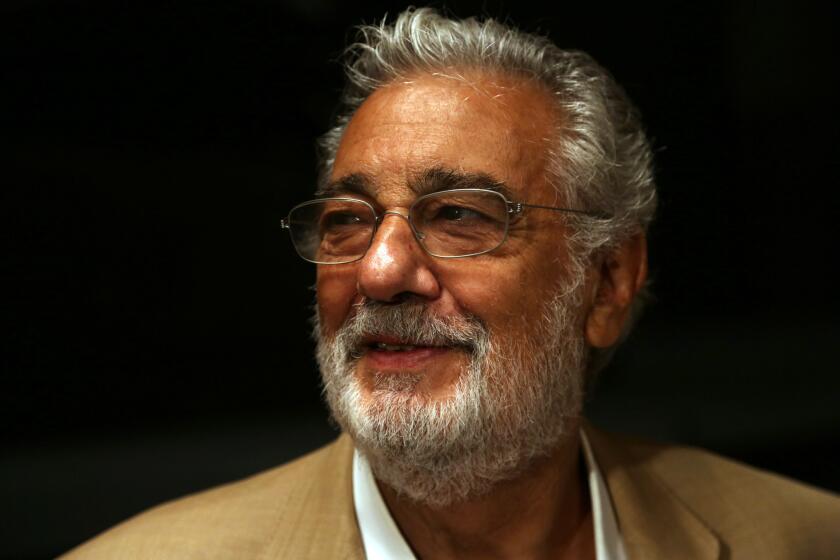

Why the Plácido Domingo sexual harassment investigation brings questions, not answers

A week after nine women in an Associated Press report accused opera star Plácido Domingo of sexual harassment, Los Angeles Opera promised to conduct a “thorough and independent investigation” into the allegations against its general manager.

But the clarity of that phrase — “thorough and independent investigation” — belies a murky truth: These kinds of investigations historically have raised more questions than they have answered, leaving victims and the public in the dark about what behavior was documented in the inquiry, who might share some responsibility for wrongdoing and whether institutional problems that allowed misconduct to fester have been, or will be, rectified.

Domingo issued a statement calling the allegations in the AP article “deeply troubling, and as presented, inaccurate,” and L.A. Opera declined to comment while its investigation is underway. But advocates for victims of sexual misconduct said the Domingo case was already following a predictable and troubling script, largely because of the inherent conflict of interest that arises when arts companies essentially lead inquiries into themselves, with each investigator usually answering to a board of directors.

A chief complaint: Organizations hire outside counsel to conduct an investigation but often keep the findings completely secret, said Ariela Gross, a professor of law and history at USC Gould School of Law and chairwoman of Concerned Faculty of USC, which formed in response to scandals that have grown to include university admissions, alleged sexual assault by a campus gynecologist and drug use by the former medical school dean.

“It may be the board uses the findings to fire people or make structural changes, but they don’t make known why,” Gross said. “It’s very hard to evaluate because nobody other than the recipients actually know what the report said.”

Allegations against Harvey Weinstein may have made #MeToo a movement in Hollywood and beyond, but in the nearly two years since that case broke, internal investigations into sexual misconduct often have protected the accused. That is proving as true in the realm of nonprofit arts as it has in the corporate worlds of film and TV.

Accusations of harassment against Plácido Domingo dating back to the 1980s raise many questions, and generate a statement of denial from the opera legend.

In one common scenario, an arts organization hires an investigator who declares there’s no evidence to support accusations, and the alleged victims and the public are left to accept that finding as truth. The details of the investigation are never released, as was the case of Peter Martins, former chief of New York City Ballet.

In another scenario, an investigation does lead to a firing or some other disciplinary action against the accused, but again, the company does not release detailed findings. Such was the case of popular guest conductor Charles Dutoit, who has denied women’s accusations of sexual misconduct. Although the Boston Symphony Orchestra, among others, found accusations to be credible, at least one alleged victim has disputed the investigator’s contention that management had not been aware of improper behavior.

In still other cases, a company may not even say whether an accusation was deemed credible. At American Ballet Theatre, popular principal dancer Marcelo Gomes quickly resigned in 2017 amid an investigation of misconduct. ABT ended its investigation without declaring any official findings from the inquiry and on Tuesday referred The Times to its original statement announcing Gomes’ departure. Gomes, meanwhile, has moved on to dance with other companies; in August he was a guest artist at the Festival Ballet Theatre gala in Costa Mesa.

Compared with criminal investigations, internal inquiries might have dramatically different standards of proof or a sharply limited scope. Chronic secrecy can leave victims feeling unprotected and without closure, left to speculate whether the outcome of an investigation had been decided before it even started.

L.A. Opera raised eyebrows with its choice of investigators. Debra Wong Yang of Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher is the same lawyer hired by USC to investigate Dr. Carmen A. Puliafito, the former medical school dean who partied with drug addicts and criminals and was caught on video using drugs. Skeptics questioned how a lawyer who had represented the university in at least four lawsuits could truly offer an impartial investigation encompassing top USC administrators.

Whether the public will get to see a written report of the Domingo investigation is among the many questions that L.A. Opera has not answered. The company referred The Times’ questions to Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher. The firm, in turn, did not respond to a request for comment.

Who will Yang report to at L.A. Opera — the board of directors or, as some victims advocates have suggested, a specially appointed group of objective directors with few ties to the company? Will the investigator observe a statute of limitations or will she look into accusations against Domingo that date to the 1980s? Is the scope limited to the nine women in the AP article or will Yang interview others? Is the investigation specific to Domingo, or given the AP article’s insinuation that others helped to protect the opera star, will the actions or inaction of company leaders be part of the investigation?

How big is Yang’s team of investigators? Given that she is also representing USC in the ongoing college admissions scandal, how involved can she be in the L.A. Opera inquiry?

Finally, and perhaps most vexing, victims advocates say, how do you investigate an icon who goes back decades with many people in the company and on the board?

Sometimes it takes litigation for the depth and breadth of allegations to become public. Sexual abuse accusations against the Metropolitan Opera’s famed conductor and music director James Levine led to his firing in 2018, but the Met did not release its investigation publicly. Details spilled out after Levine, who has said he is innocent, sued the Met for breach of contract and defamation, and the Met responded with a countersuit cataloging the allegations.

“An employer doesn’t have any legal obligation to make the results of an investigation public, and in fact has to be somewhat careful with that information because sometimes there may be legal restrictions on what can be shared,” said Jessica Stender, senior counsel for workplace justice and public policy at Equal Rights Advocates, a civil rights organization that advocates against gender discrimination. “A fear of defamation lawsuits from people who were alleged to have engaged in sexual harassment may underlie employer hesitance to discuss the specifics of an investigation or discipline.”

Such legal repercussions may inspire secrecy, as does a deep desire to protect the reputation of the larger organization, including board members who are often wealthy, well-connected and powerful members of the community.

Former New York City Ballet dancer Wilhelmina Frankfurt called her former company a “cabal” because of how it investigated accusations of sexual, physical and verbal abuse by former chief Martins, who retired in January 2018 but steadfastly proclaimed his innocence.

The Martins investigation was conducted by outside counsel Barbara Hoey. In February 2018 — in a report that never was made public — she declared that the accusations against Martins could not be corroborated.

The clearing of Martins was a foregone conclusion, said Kelly Cass Boal, another one of the company’s former dancers.

“I never had one ounce of hope that [the investigation] was real,” Boal said. Hoey treated her like “the bad guy” while investigating her claims, which included an instance when Martins choked her and screamed at her after a tense rehearsal, Boal said.

Frankfurt felt that the investigation was meant to protect Martins and the integrity of New York City Ballet. She said that Hoey would not allow her to bring a witness to her interview unless they both signed a nondisclosure agreement. She refused.

“His history of abuse, I believe, was covered up for years and years,” Frankfurt said. When Hoey cleared Martin of wrongdoing, Frankfurt felt disgusted. She said the secrecy of the investigation amounted to the condoning of sexual assault. “It’s morally wrong and it’s inhumane. It doesn’t protect vulnerable human beings, and these organizations are supposed to be about these beautiful artists.”

Hoey did not respond to The Times’ request for comment.

Despite the accusations he faces in America, or perhaps because of them, Plácido Domingo is lavished with cheers at the Salzburg Festival in Austria.

Difficulties in fairly and transparently handling misconduct investigations won’t be fixed anytime soon, victims advocates say. The problem comes down to a scarcity of options. Handling an investigation internally, using a human resource department or others inside the company, can present an even larger quandary.

“Employees don’t have faith that an internal HR person will be objective and neutral, and [they] fear that person will take the side of the employer and is inherently biased,” said Stender, the workplace justice advocate.

Looking to performers’ unions for protection also gets complicated. The firing of New York City Ballet dancers Zachary Catazaro and Amar Ramasar for sharing sexually explicit nude photos of female dancers was protested by their union, the American Guild of Musical Artists, and eventually an arbitrator ordered both performers to be reinstated.

That leaves victims relying on companies to police themselves, to be morally just and to do the right thing — which is how, many would say, #MeToo became such an issue in the first place.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.