How Christian Marclay is turning Snapchat messages into sound art

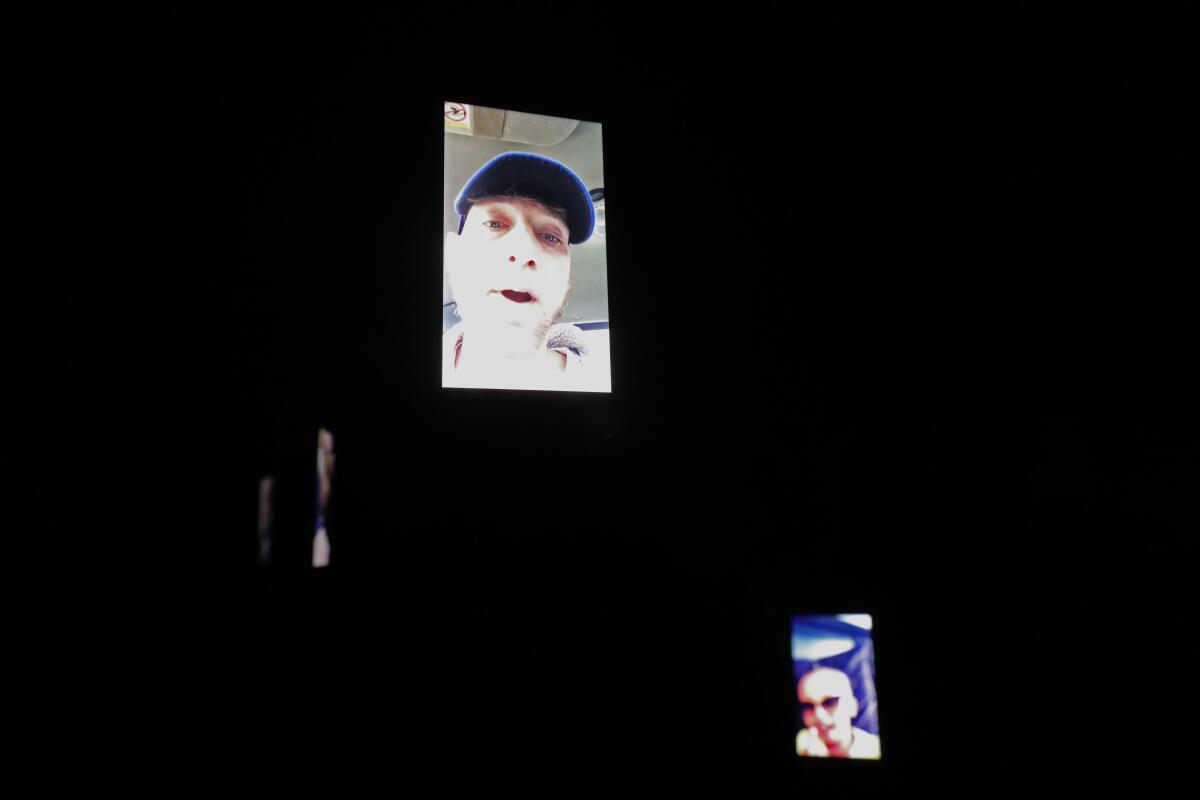

Inside a pitch-dark room at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art hang 42 cell phones, making a room-sized mobile that looks like the sort of dystopic technological device you might find in an episode of “Black Mirror.” Each handset bears a simple command in white letters on a black screen: “Talk to Me Sing to Me.”

I say, “Hello.”

For the record:

12:22 p.m. Aug. 30, 2019An earlier version of this story reported that Snapchat users publish 3.5 billion videos daily. They publish 3.5 billion Snaps daily — which includes still photographs.

The phone screens light up with a brief burst of video, each with different images. The cacophony somehow echoes the tones in my voice. Then, just as quickly as everything appeared, the screens go black.

I say “hello” a second time and the room is once again illuminated with crude cell phone shots that reveal people of all genders, ethnicities and races sprawled on couches, chilling in beds and sitting around kitchens, chattering into the camera. I can’t hear what they say, but their collective inflections mimic my own. Again, in an instant, they are gone.

The piece, titled “Talk to Me / Sing to Me,” is part of “Sound Stories,” a new exhibition by composer and multimedia artist Christian Marclay, who uses public videos uploaded to the social media platform Snapchat as his primary material in the installations. A team of engineers from Snap Inc., Snapchat’s parent company, led by the company’s director of engineering, Andrew Lin, collaborated with Marclay on the project by developing algorithms that could help filter and organize videos based on their sonic qualities.

“It was more the sound that I was looking for rather than action,” says Marclay as he steps gingerly through darkened galleries in the midst of installation. “It was listening rather than looking.”

And the listening turned up some interesting sounds.

“The potato chips — the crunchy potato chips,” he says. “The sound of broken iPhone glass, that is interesting. Scratching ice. I thought, ‘Wow, I could make a symphony out of these.’”

Marclay, 64, was born in California, raised in Switzerland and is now based principally in London. Throughout his career, he has created works that take elements of cultural ephemera — bits of video, fragments of sound, old cassette tapes — and rearranges them into something bigger than the sum of their parts.

This summer, his video “48 War Movies,” installed in the Arsenale at the Venice Biennale (ongoing through Nov. 24), drew the attention of critics for the ways in which it visually and audibly nested several dozen war films into a single, explosive work. (It will go on view at New York’s Paula Cooper Gallery next month.) At the Biennale’s Giardini exhibition space, Marclay’s woodblock print series “Scream,” an homage to Edvard Munch, is on display.

But Marclay is perhaps best known for his 2010 work, “The Clock,” a looped, 24-hour montage of film and television clips that dwells on clocks and the passage of time and is screened in such a way so that the time in the film always parallels real time. (When it is noon in the film, it is noon in the theater.)

The piece was a smash from the moment it first landed at Paula Cooper Gallery in February 2011, generating lines around the block. Shortly thereafter it was acquired by LACMA, which also held screenings of the work — one of which drew the attention of an arts organization across the street, which served free doughnuts to Marclay fans for an entire 24-hour screening cycle.

Despite this brush with viral fame, Marclay is hardly a natural for any project involving social media.

“I don’t do anything,” he says, looking perplexed at the idea of continuous connection. “I do email. That’s it.”

In fact, when he was first approached by Snap Inc. for a possible commission, his first instinct was to turn the offer down. Says Marclay: “Everyone said, ‘Don’t go that route.’”

But he grew curious when the company told him that users create 3.5 billion Snaps daily.

“That,” says Marclay, “was staggering.”

“What’s surprising is the similarity and the banality,” he says. “And the fact that people around the world do the same things with their phone. ... It’s a new form of language — a very visual language.”

But by and large, the five installations in “Sound Stories” are more about sound than they are about visuals.

“In these little snippets of what happens in the world you can find music.”

— Andrew Lin, Snap, Inc.

“Tinsel Loop,” from 2018, employs sonic elements from Snapchat videos to play a lullaby-ish 18-note Marclay composition, “Tinsel,” which was designed to be played on a music box. Accompanying the sound is the video, facing off on a pair of screens, but it is incidental to the tune that is generated — one drawn from the sounds of phone pings and automotive bleeps and cats meowing. Every time the tune repeats, it draws from a new collection of Snapchat fragments, so that each version of “Tinsel” sounds like a variation of a theme.

His use of incidental sound is at its most dramatic in a room-sized installation called “The Organ,” from 2018. The piece is interactive, consisting of an organ that sits at the center of a darkened room. Hit a key and the organ plays that note by playing a column of videos that appears on an overhead screen. Hit multiple keys and multiple columns appear. Rest your arm on the keyboard and everything lights up. (I used the organ to play the only ditty I know: “La Polka de Los Perros.” A combination of incidental noise bleeted out a recognizable version of the tune.)

“There is a lightness” to Snapchat, says Marclay. “That playfulness, I think, was kind of important to me.”

All of this required stripping sound from hundreds of millions of videos, analyzing the sounds, assigning a pitch to them, then whittling the pile to a manageable “few hundred thousand” — the sort of work that would have taken Marclay several lifetimes to complete. And that’s where Snapchat‘s engineering team came in.

“We built a suite of computers that could do the audio analysis on these tracks,” says Lin. “It basically can take a signal and break it up into all of its component frequencies.”

These were then reviewed individually by engineers to confirm the pitch and make sure that video didn’t violate Snapchat’s community guidelines. For some installations, Marclay then made further refinements.

In “All Together,” he collaged like images (feet walking) and sounds (the crackle of food frying gives way to the patter of rain). In “Talk to Me / Sing to Me,” he selected only videos with faces.

“It’s that small, intimate relationship,” he says of the way people interact with their phones — and the presumptive audiences that reside at the other end. And he wanted visitors to the gallery to face the individuals who produced the sounds. “It forces a collective behavior. If you have many people in a room, you have to listen.”

In the installation, Marclay isn’t simply interested in presenting sound. He is interested in exploring the unique languages and social conditions that are emerging as a result of social media.

Curator Rita Gonzalez, who helped organize the LACMA version of the exhibition (the installations were previously shown last year at the Cannes Lion International Festival of Creativity), says the work not only captures the whimsy of digital missives, but the plaintiveness, too.

“The more time I spend in it, the more I felt like there was a loneliness to it,” says Gonzalez of “Talk To Me / Sing To Me.” “People are speaking into a phone hoping to find a connection and hoping someone will listen to them.”

“It’s very performative — especially with all the filters,” says Marclay, of the ways in which people broadcast themselves. “Certain things go viral because those things are quite unusual but the rest is banal and not that interesting, but it says something about you. It is a mask.”

Lin says that working with Marclay has made him think about the ways in which language and sound can be sculpted.

“Like when people say ‘ah’ or ‘um,’ those make interesting notes,” he says. “You can string that together and make something really interesting. In these little snippets of what happens in the world you can find music.”

For Marclay, it’s about showcasing sound that is heard but perhaps goes unnoticed.

“I wanted to focus on the sound element which people don’t think about,” he says. “Like you film something and you record the conversation next to you and you don’t pay attention to it. I wanted people to realize that they had a microphone in their hands.”

And yet none of this has convinced Marclay to download Snapchat on his own phone.

“Though,” he says, “they tried very hard to get me on.”

Christian Marclay: "Sound Stories"

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.