There are artists who shape the history of art through their outsize presence in the collective consciousness. There are other artists who shape the history of art through their quiet commitment to craft and their dedication to teaching. Don Suggs was one of the latter.

The painter, known for his wry, carefully composed investigations into the nature of art making — say, analyzing every shade of paint used in Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles D’Avignon,” then rendering those shades in abstraction — was also profoundly dedicated to his students as a professor of painting and drawing at UCLA, where he taught for more than three decades.

“He was never the person who wanted to appear in the spotlight,” says Elizabeth East, a director at L.A. Louver, the gallery that represented Suggs. “But he became to many people, the sun to which they were drawn.”

Suggs died July 30 at age 74 after being struck by a vehicle near his Los Angeles studio. The death was confirmed by L.A. Louver and his wife, painter Linda Stark.

“He encouraged me and mentored me, patient, kind and brilliant,” said Stark via email, “and helped me develop a way to draw as a singular practice.”

“We were on call for each other at a moment’s notice,” she added, “to extend advice or just respond.”

He was never the person who wanted to appear in the spotlight. But he became to many people, the sun to which they were drawn.

— Elizabeth East, L.A. Louver

In an Instagram post that helped to deliver news of his death, L.A. Louver described Suggs as “a person of integrity, intellect and conviction,” someone who “helped lay the foundation of our Los Angeles community.”

Suggs had a long history with the gallery, the two maturing together as artist and institution. He participated in L.A. Louver’s first exhibition, a two-artist show in 1976 that also featured work by painter Vida Hackman. The gallery was also the site of Suggs’ first solo exhibition a year later. And he was the first artist to be picked up for full-time representation there.

At the time, Los Angeles stood at a distant remove from buzzy cultural centers and art markets in New York and Europe.

“The county museum had only been around [as a standalone museum] since 1965,” says L.A. Louver’s founding director Peter Goulds. “The community of artists that formed here, that generation ... it was Rabelaisian, it was anarchic, almost. And Don was the master of this. His influence was enormous.”

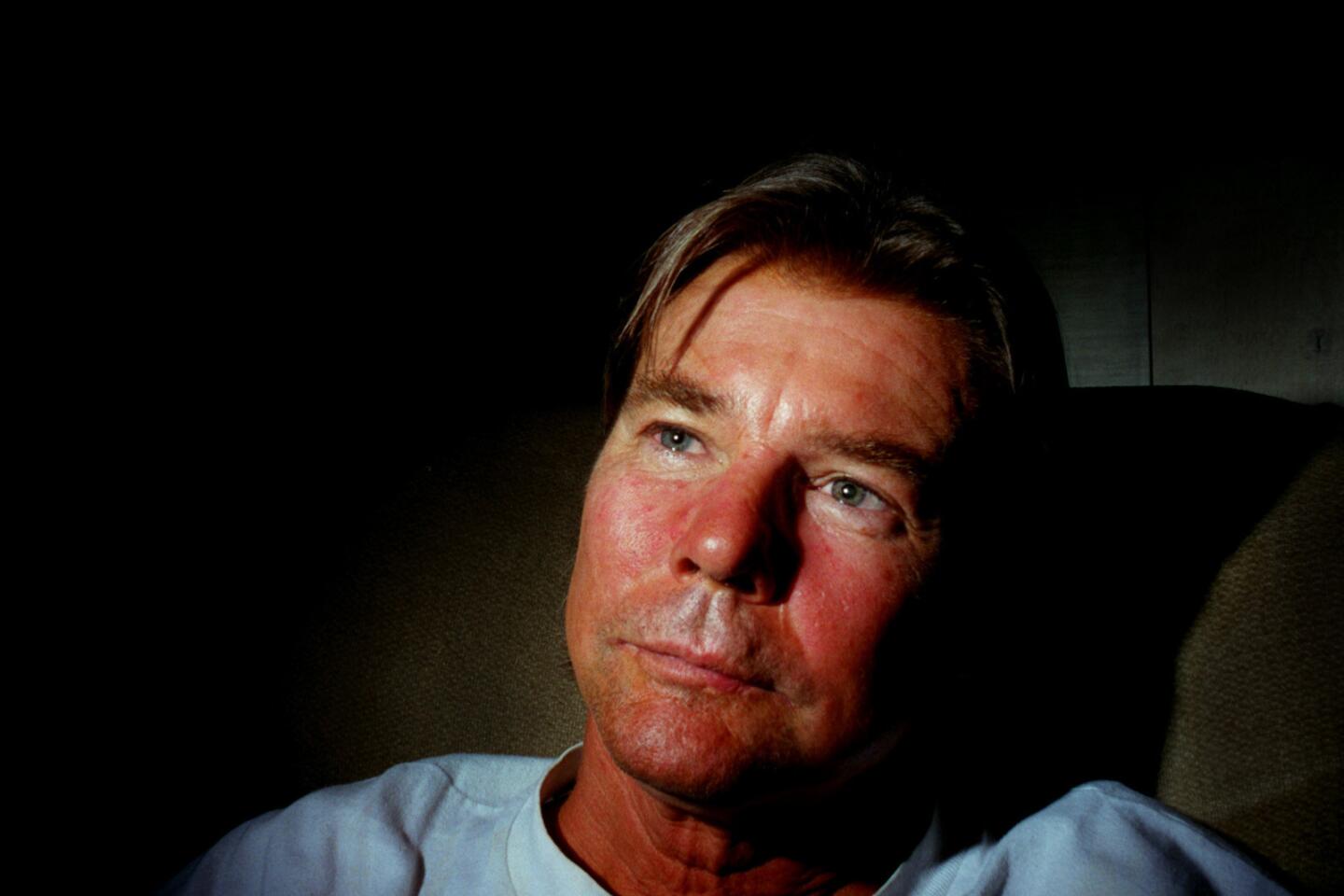

Artist Don Suggs in his studio in 2012.

In this universe, Suggs was never the showman but instead functioned as a steadying presence.

Tall, gravel-voiced, with an easy manner, he had the ability to deliver a dry joke or a sardonic jab. He was an educator who was swayed not by trends but by the urge to help students refine their ideas; an artist who put more effort into art-making than career making — producing meticulously crafted works that served as paeans to color and concept, building his own tools when those that were available fell short.

He also rarely repeated himself, resisting the pressure to make art that settled into a rut of the easily recognizable — a habit that kept him under the radar.

Suggs produced, over a career that spanned five decades, wildly different sorts of art: totemic sculptures made out of cheap plastic objects acquired at flea markets, paintings that investigated the nature of color in art history, and large photographs that, upon closer inspection, fragmented into myriad shards. These disparate works were all united by an unrelenting, years-long investigation into the nature of art and looking.

In 2007 he was the subject of a survey at Otis College of Art and Design’s Ben Maltz Gallery that pulled together works produced over 38 years. The title of the show, “Don Suggs: One Man Group Show,” nodded to the ever-evolving nature of his work — something that Times contributor David Pagel praised in his review.

“Every time you turn your head, there is something new to see: 25 lima beans glued to an aerial photograph of the suburbs or brightly colored plastic service dishes nestled inside one another to form super-size blossoms Suggs calls ‘Fleurs du Mall,’” he wrote. “Every path through the gallery feels off the beaten path, far from the streamlined, prepackaged experiences mainstream culture serves up.”

Born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1945, Suggs was raised in San Diego but moved to Los Angeles to earn his bachelor’s in the arts at UCLA in 1962. He then ended up sticking around for two master’s degrees.

Teaching jobs in Florida and New Hampshire followed. But soon he made his return to Los Angeles, holding positions at the University of Southern California and at Otis. He landed as a professor at UCLA in 1983 and remained there until his retirement in 2014.

There he built a fierce following among students for his ability to sharpen their work — whatever that work was.

“He would walk into a student’s space and could assess what they were doing, without projecting his own agenda,” says painter Rebecca Campbell, a friend and former student.

“I was at UCLA, but I’m not a theory-heavy person,” she adds. “I came from this very religious environment that didn’t want me to be an artist and I end up at this place where the people there have been to MOCA every weekend. I needed to speak some narratives and he recognized that.”

If Suggs inspired his students with his dedication — he was renowned for showing up at their openings long after they had left the university — he also inspired them with the quiet devotion he had for his own work.

“It was this ever-evolving pursuit of curiosity,” says Campbell. “He was interested in so many things: science, politics, formalism. He didn’t put parameters on the work.”

That meant never sticking to a single, formal style.

In the ‘80s, Suggs created paintings that placed bands of color — suggestive of the patterns of national flags — over images of people’s faces and landscapes, as much a comment on minimalism and portraiture as it was about nature and nationalism.

A decade later, he was digging into photography, creating large composite photographs of tourists at prominent landscapes out of a quilt-like arrangements of photographic fragments. The uncanny repetitions and cubist placements could leave viewers feeling as if they’d stepped into a glitch in the Matrix.

His work, however, was united by long-running intellectual threads, says curator and critic Doug Harvey, who helped organize Suggs’ survey at Ben Maltz.

“He was able to draw on all kinds of contemporary and historical stylistic modes to explore the relationship between the formal and narrative qualities of art,” Harvey said via email, “and how they they combine or interfere with one another to generate meaning.”

2/33

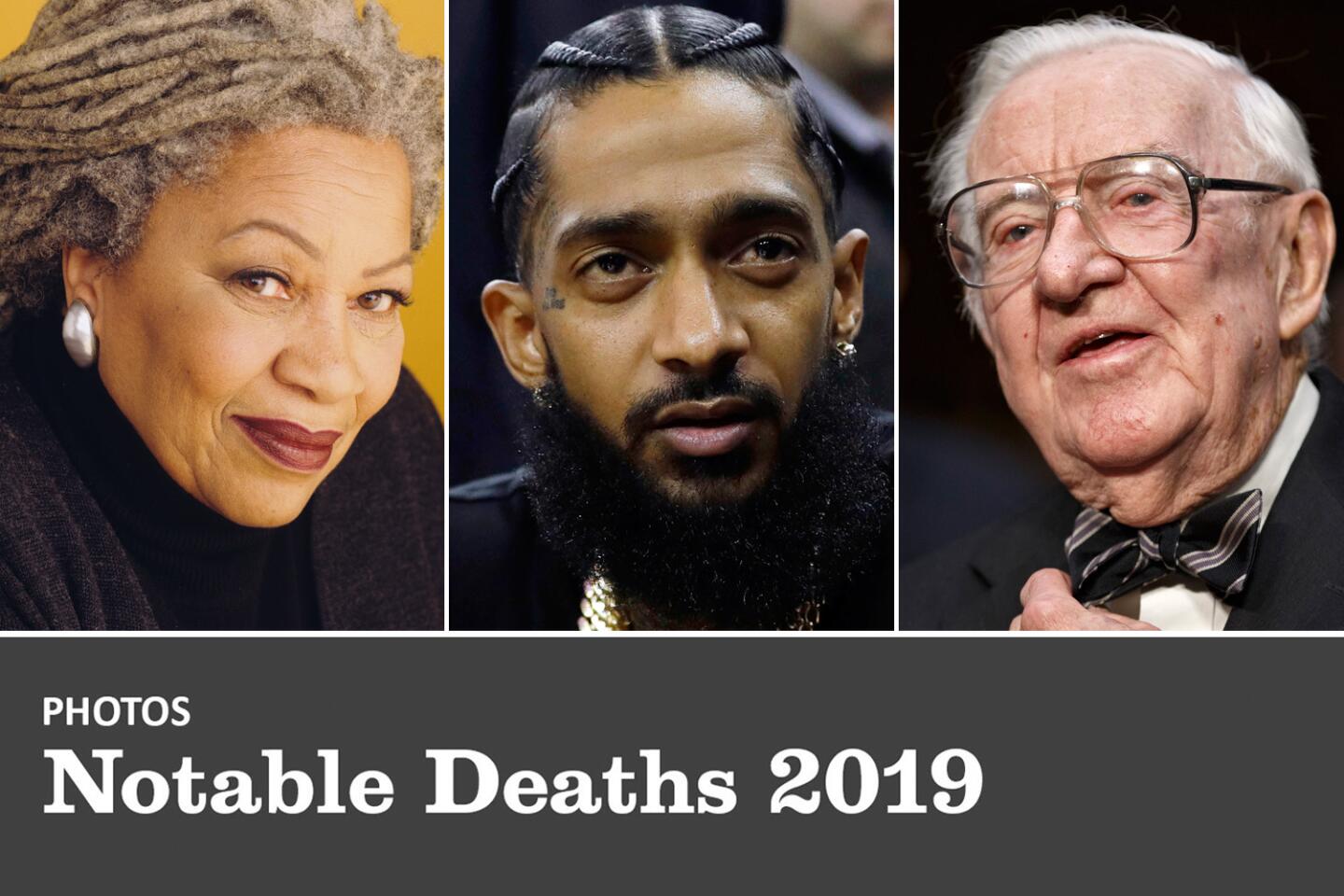

Pioneering shock jock Don Imus was one of radio’s most popular and polarizing figures. Born in Riverside, he became a top broadcaster in New York, but he also sparked a national firestorm in 2007 with a racist remark about the Rutgers University women’s basketball team. He was 79. (Richard Drew / Associated Press)

3/33

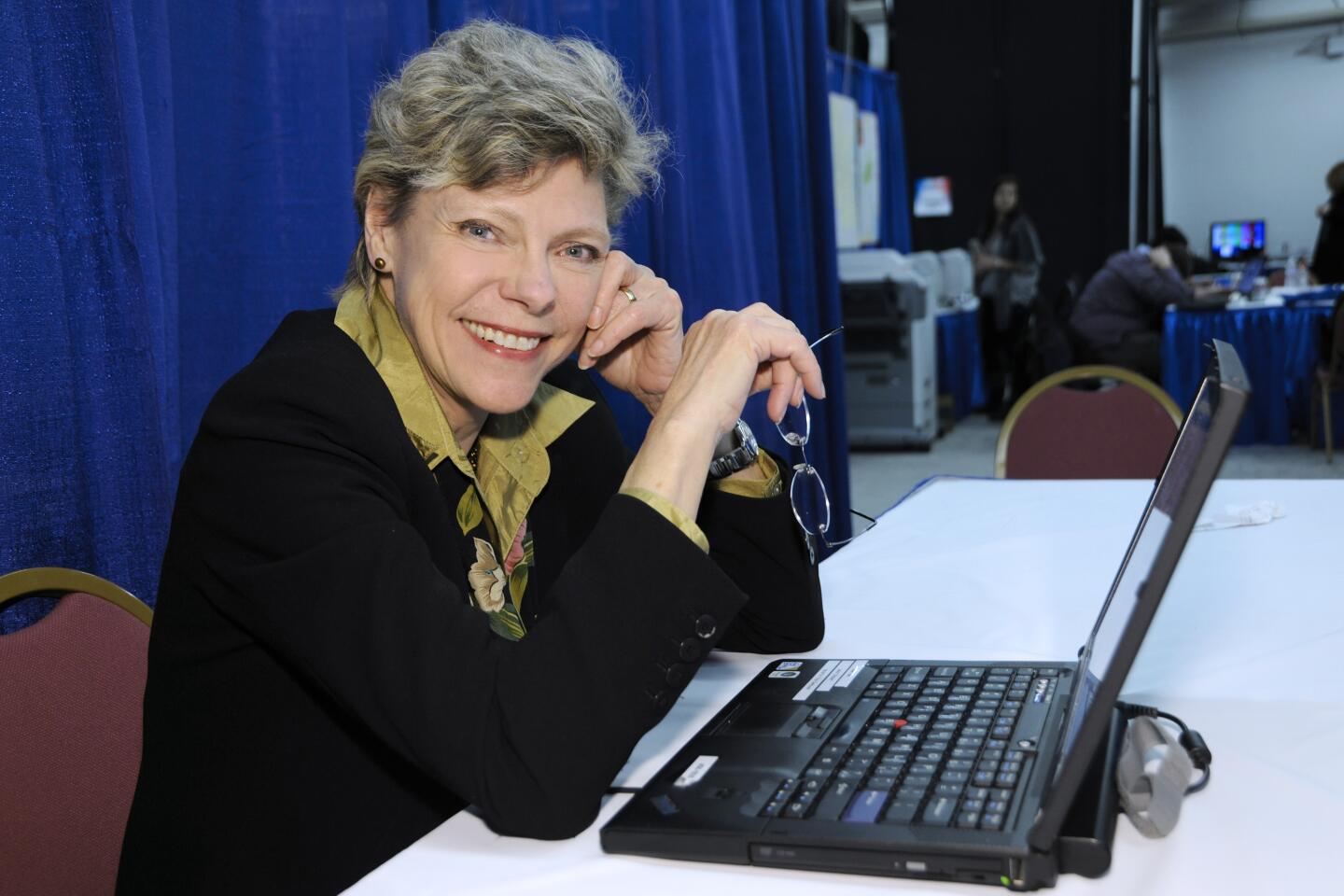

Cokie Roberts covered Washington from Jimmy Carter to Donald Trump for NPR and ABC News. A co-anchor of the ABC Sunday political show “This Week” from 1996 to 2002, Roberts devoted most of her attention to Congress, where her father Hale Boggs was a House majority leader until his death in 1972. She was 75. (Donna Svennevik / Walt Disney Television via Getty)

4/33

T. Boone Pickens followed his father into the oil and gas business and built a reputation as a maverick, unafraid to compete against industry giants. In the 1980s, Pickens sought riches on Wall Street by leading bids to take over big oil companies including Gulf, Phillips and Unocal. Even when he failed to gain control of his targets, he scored huge payoffs by selling shares back to the company and dropping the hostile takeover bid. He was 91. (Riccardo Savi / Getty Images)

5/33

When Robert Mugabe took over as Zimbabwean president in 1980, he was celebrated as a hero in the liberation war against Britain. But after international sanctions, a series of fraudulent elections and an economic collapse sparked by the seizure of white-owned farms, Mugabe become a pariah and retired in 2017 rather than face impeachment. He was 95. (Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi / Associated Press)

6/33

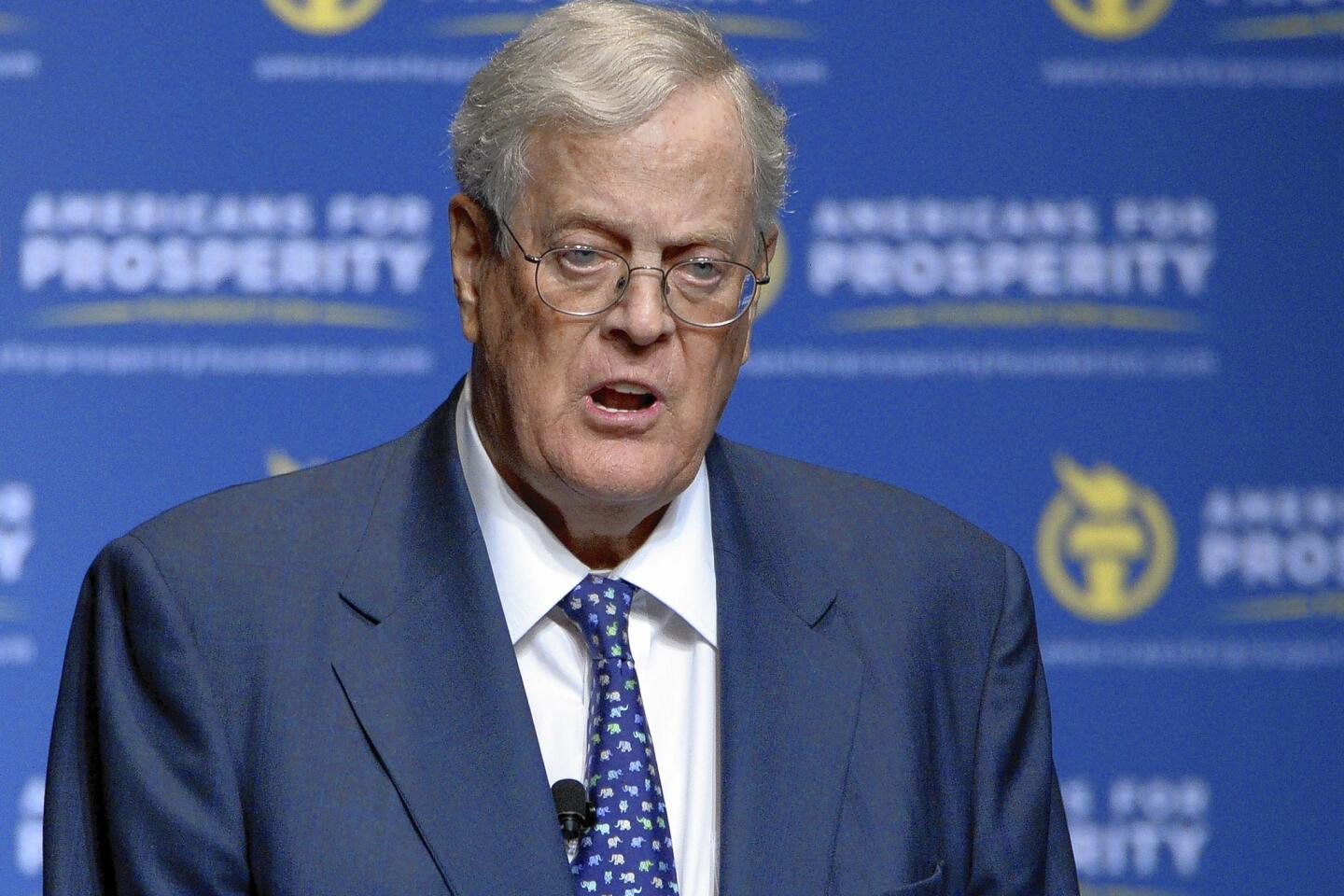

David Koch was the aide de camp to Charles, his older brother, as the two leveraged the family fortune to push American politics to the right. The Koch brothers pushed the boundaries of dark money in politics and fueled a backlash against environmental regulations and government programs such as healthcare and mass transit. He was 79. (Phelan M. Ebenhack / Associated Press)

7/33

Peter Fonda was the son of a classic Hollywood star and a key player in the 1969 countercultural road trip saga “Easy Rider,” which he co-wrote and produced. The screenplay earned Fonda his first Academy Award nomination; his second came in the lead actor category for the 1997 independent film “Ulee’s Gold.” He was 79. (AP)

8/33

Hard-line Chinese premier Li Peng was best-known for ending the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests with a bloody crackdown by troops. A keen political infighter, he spent two decades at the pinnacle of power before retiring in 2002, leaving a legacy of prolonged economic growth and authoritarian control. He was 90. (AP)

9/33

Chris Kraft, shown with President Reagan in 1981, never flew in space but was the creator and longtime leader of NASA’s Mission Control. The legendary engineer served as flight director for all Mercury flights and seven of the Gemini flights, helped design the Apollo missions and later oversaw the beginning of the shuttle era at Johnson Space Center. He died just two days after the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s moon landing. He was 95. (AP)

10/33

Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens joined the court as a centrist Republican but emerged in his later years as the leading voice of its liberal bloc. Appointed by President Ford, Stevens played a key role in decisions that preserved a woman’s right to abortion, maintained a strict separation of church and state, and put limits on the death penalty. He was 99. (AP)

11/33

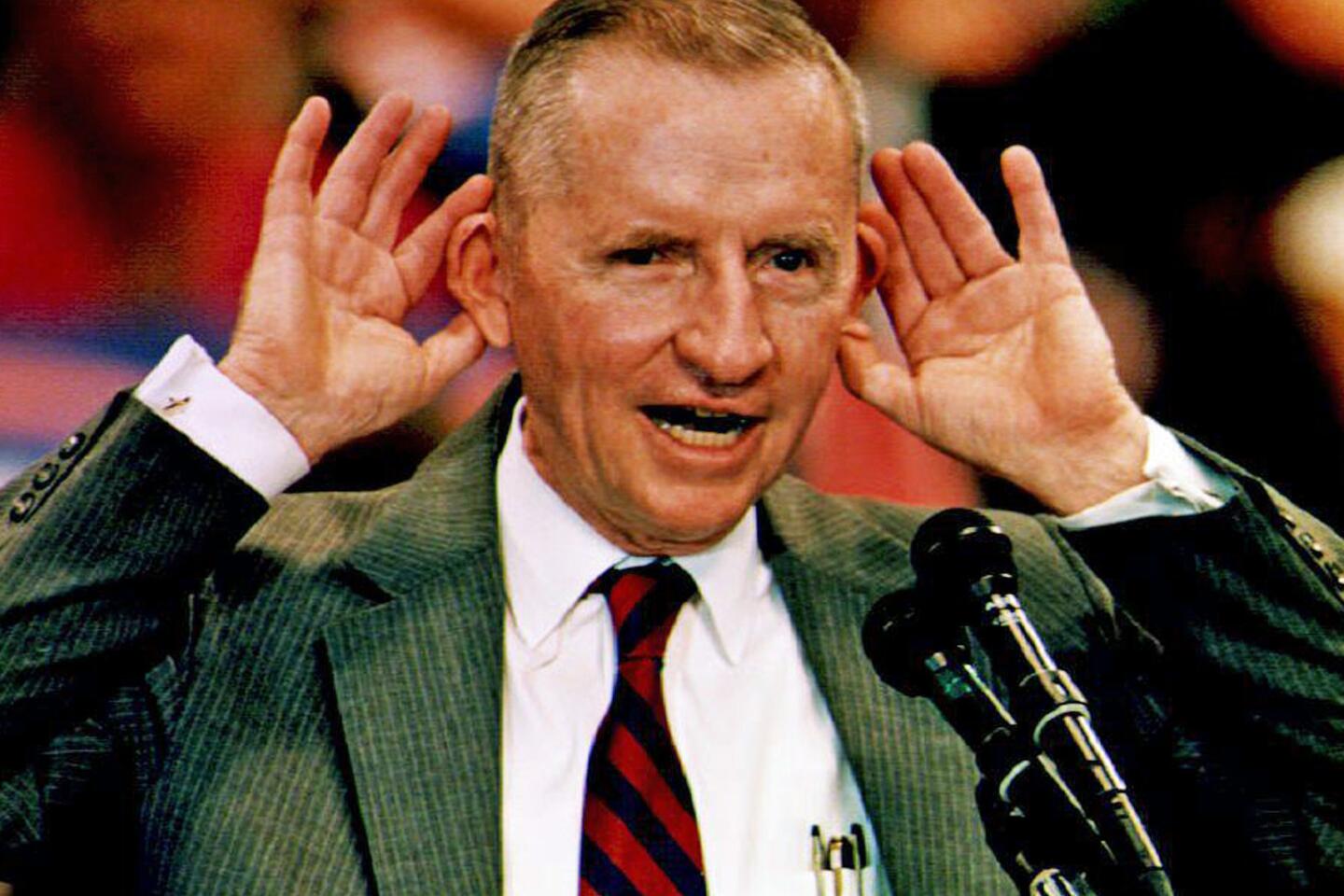

Billionaire Ross Perot blazed across America in the 1990s as a third-party presidential candidate and won nearly 19% of the popular vote in the 1992 election, finishing third behind Democrat Bill Clinton and Republican President George H.W. Bush. The diminutive Texan was an early tech entrepreneur who founded Electronic Data Systems, a computer services company, in 1962 with $1,000 in savings. He was 89.

(Peter Muhly / AFP/Getty Images) 12/33

Pitcher Tyler Skaggs grew up an Angels fan in Santa Monica and joined the organization as a first-round draft pick. He battled injuries throughout his career but started 24 games last season and showed signs of dominance this year. He was 27.

(Charlie Riedel / AP) 13/33

Judith Krantz wrote blockbuster romance novels including “Scruples” and “Princess Daisy” that sold more than 80 million copies worldwide. Her books have been translated into more than 50 languages, and seven have been adapted as TV miniseries, with her late husband, Steve Krantz, serving as executive producer for most. She was 91.

(Aaron Rapoport / Getty Images) 14/33

Italian director Franco Zeffirelli was best-known for his films, including the 1968 critical and box office hit “Romeo and Juliet” and a 1990 “Hamlet” with Mel Gibson. His massive opera productions included a version of Puccini’s “La Boheme” that became the most-often presented production in the Metropolitan Opera’s history. He was 96.

(Paolo Cocco / AFP/Getty Images) 15/33

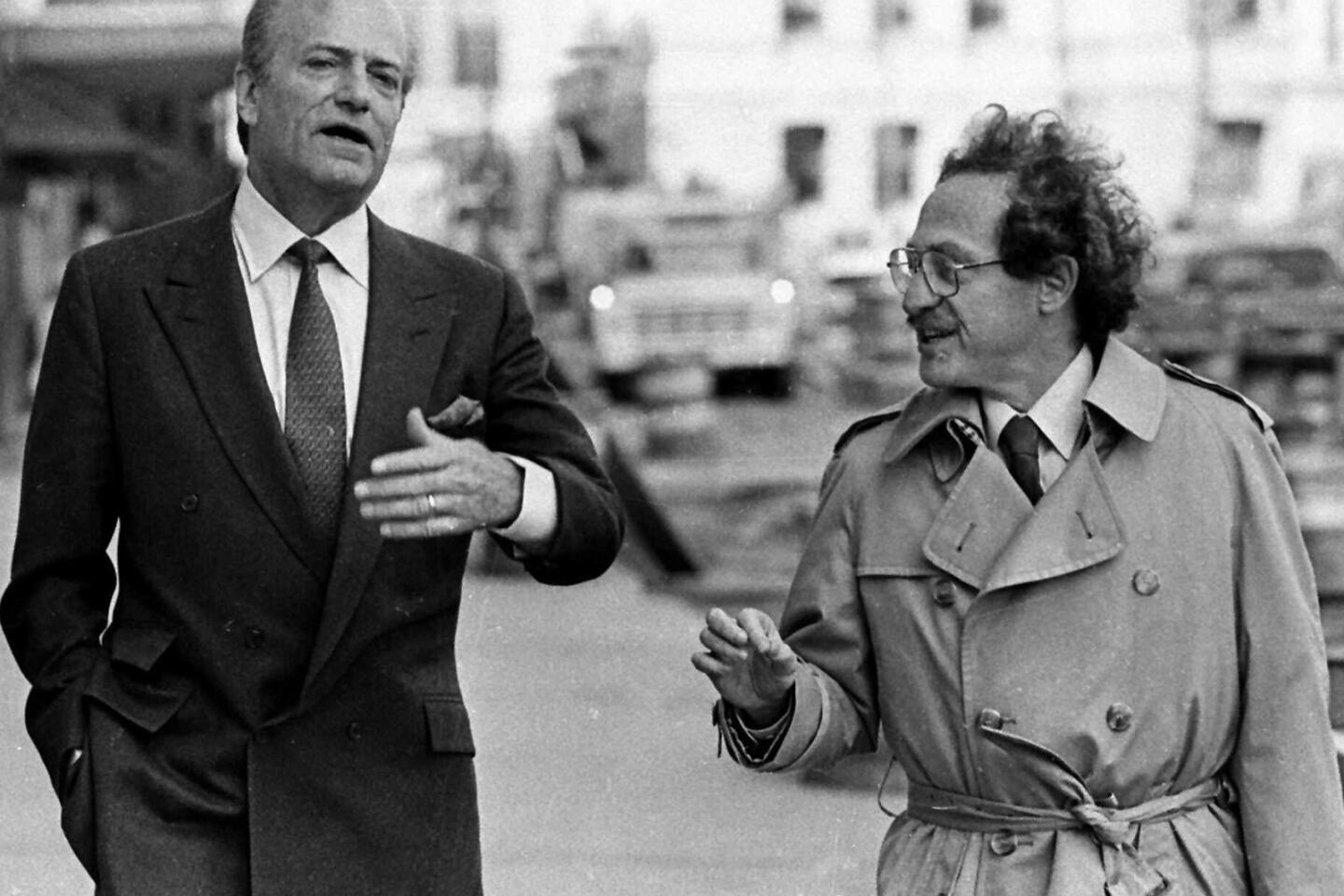

Danish-born socialite Claus von Bulow, left, shown with attorney Alan Dershowitz in April 1985, was convicted in 1982 and then acquitted three years later on two counts of attempting to murder his American heiress wife, Sunny, with injections of insulin. The high-profile case has been called one of the most sensational courtroom dramas in modern U.S. history. He was 92.

(Charles Krupa / AP) 16/33

Herman Wouk explored the moral fallout of World War II in the Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Caine Mutiny” (1951) and other widely read books. Determined to produce a “great war book,” Wouk wrote “The Winds of War” and its sequel, “War and Remembrance,” in the 1970s, and the two sweeping novels became the basis for a pair of television miniseries. He was 103.

(Douglas L Benc Jr / AP) 17/33

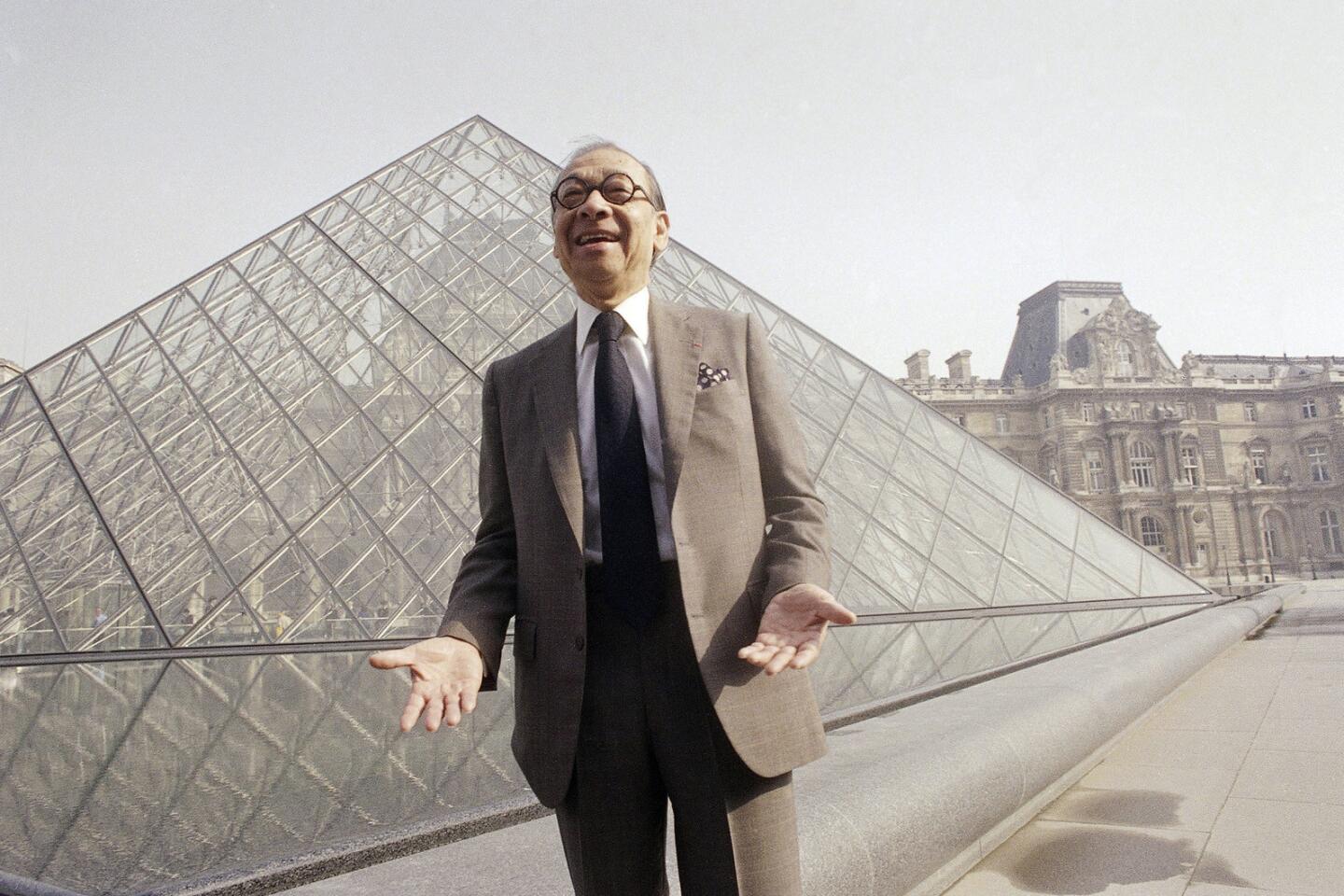

Architect I.M. Pei had a client list that included French President Francois Mitterrand for the Louvre and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis for the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library in Boston. Among several Pei projects in the Los Angeles area are the former Creative Artists Agency headquarters in Beverly Hills and the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. He was 102.

(Pierre Gleizes / AP Photo) 18/33

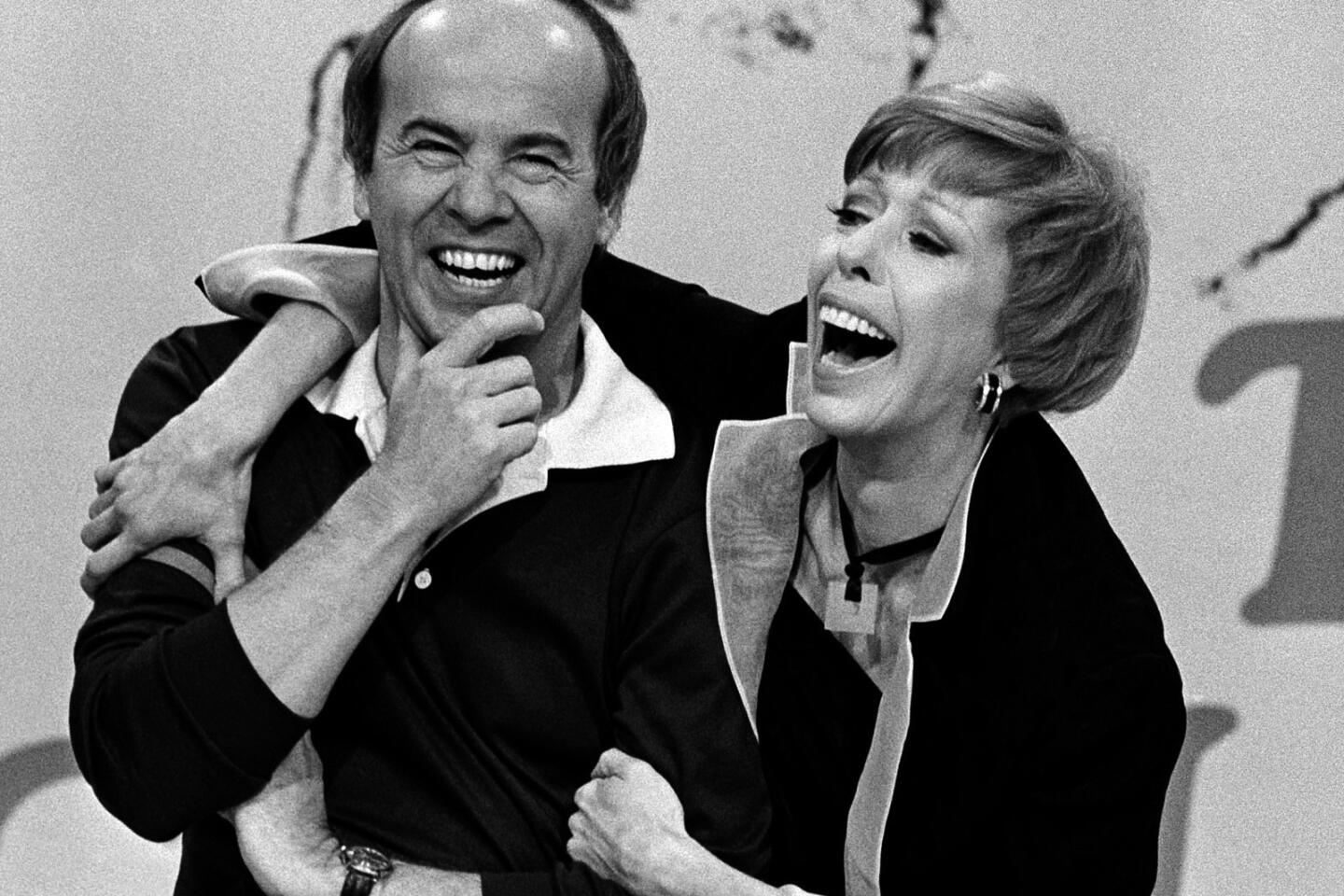

Tim Conway came to prominence on television as a bumbling ensign in “McHale’s Navy” opposite Ernest Borgnine from 1962 to 1966, then became a regular on “The Carol Burnett Show,” where he famously developed a knack for making costar Harvey Korman crack up. He also starred in the “Apple Dumpling Gang” movies in the 1970s and gained fame with a new generation as the voice of Barnacle Boy on “SpongeBob SquarePants.” He was 85.

(George Brich / AP) 19/33

John Singleton’s 1991 debut, “Boyz n the Hood,” was an inner-city coming-of-age story that earned two Oscar nominations and put the young filmmaker in the company of emerging black moviemakers such as Spike Lee and Mario Van Peebles. Singleton went on to direct “Poetic Justice” (1993), “Higher Learning” (1995) and “Baby Boy” (2001), which featured Taraji P. Henson at the start of her career. He was 51.

(Christopher Polk / AFP/Getty Images) 20/33

Grammy-nominated rapper Nipsey Hussle was gunned down outside his Marathon Clothing store in the same South L.A. neighborhood where he was known as much for his civic work as he was for his hip-hop music. He was 33.

(Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images for Warner Music) 21/33

Sidney Sheinberg, right, with Steven Spielberg and Lea Adler, Spielberg’s mother, at a 1994 Beverly Hilton gala.

(Shepler, Lori / Los Angeles Times) 22/33

Jan-Michael Vincent was a golden boy of 1970s Hollywood action films and went on to star in the mid-1980s TV adventure series “Airwolf.” But his erratic behavior and cocaine consumption was a major reason “Airwolf” was canceled. He was 74 by most accounts, but the death certificate listed him as 73.

(Alex Garcia / Los Angeles Times) 23/33

Sitcom star Katherine Helmond had memorable roles as ditzy matriarchs in “Soap,” “Who’s the Boss?” and “Coach.” Her work as Jessica Tate on the 1970s parody “Soap” earned her seven Emmy nominations, and she was nominated again in 2002 for her guest role in “Everybody Loves Raymond.” Helmond also starred in director Terry Gilliam’s films “Brazil” and “Time Bandits.” She was 89.

(Chuck Burton / AP) 24/33

André Previn conquered L.A. with his artistic genius twice: first as an Academy Award winning composer of Hollywood movie music, then as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. A conductor and pianist who toggled between classical, pop and jazz, Previn won Oscars for “My Fair Lady” (1964), “Irma la Douce” (1963), “Gigi” (1958) and “Porgy and Bess” (1959). He was 89.

(Patrick Downs/ Los Angeles Times) 25/33

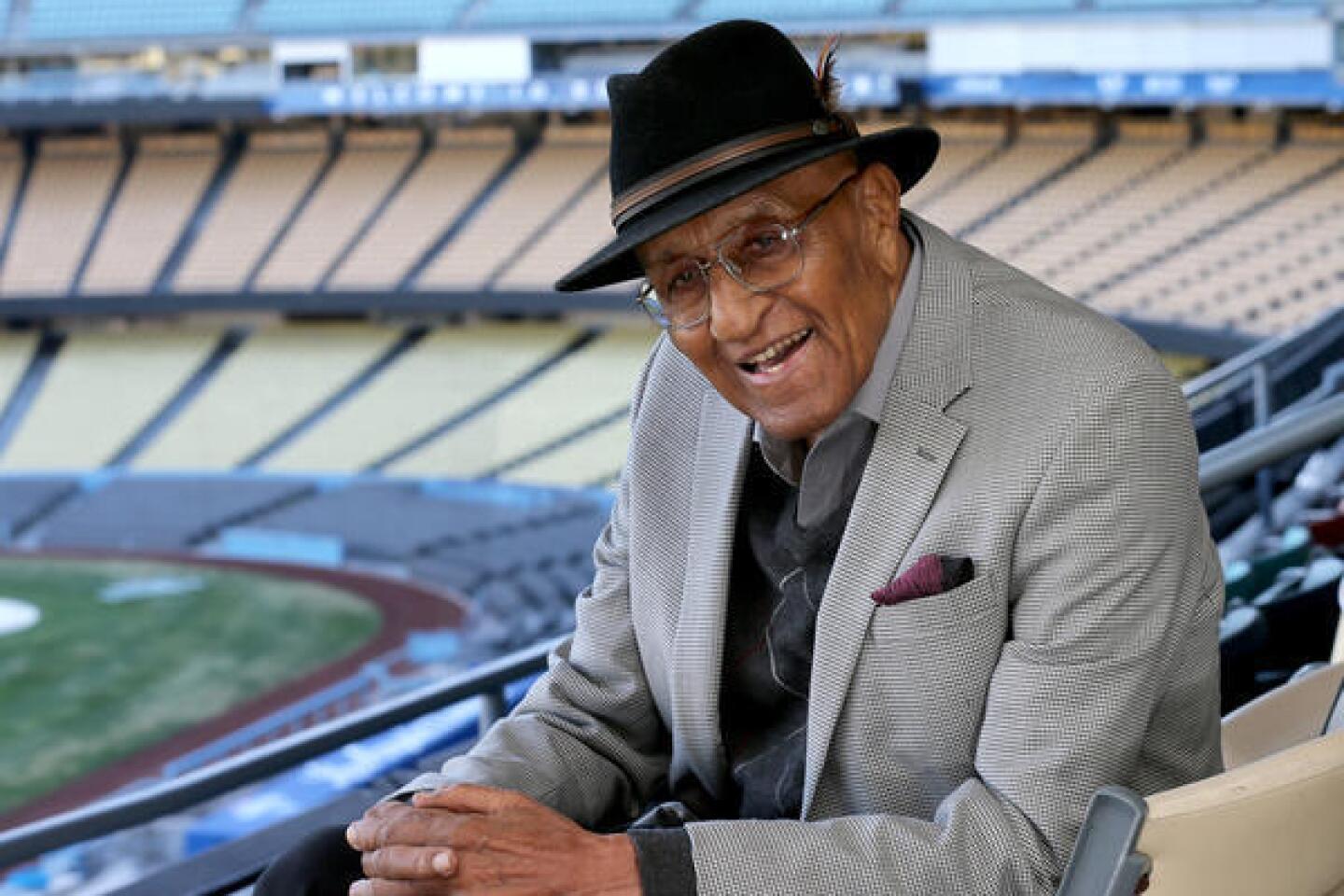

Dodgers right-hander Don Newcombe was the first outstanding African American pitcher in the major leagues and in 1949 became the first to start a World Series game. The 6-foot-4, 240-pound hurler was also the first player in major league history to have won the rookie of the year, Most Valuable Player and Cy Young awards. He was 92.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 26/33

Michigan Democrat John Dingell Jr. used his considerable power in the House of Representatives to uncover government fraud and defend the interests of the automobile industry. Known as “Big John” and “The Truck” for his forceful nature and 6-foot-3-inch frame, Dingell was the longest-serving member of Congress in U.S. history. He was 92.

(Win McNamee / Getty Images) 27/33

Albert Finney starred in films as diverse as “Tom Jones,” “Annie” and “Skyfall.” One of the most versatile actors of his generation, he played an array of roles, including Winston Churchill, Pope John Paul II, a southern American lawyer and an Irish gangster. He was 82.

(Graham Barclay / For The Times) 28/33

Michelle King was the first African American woman to lead Los Angeles Unified School District. Her major accomplishment was pushing the graduation rate to record levels by allowing students to quickly make up credits for failed classes. She was 57.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 29/33

Grammy-winning singer and songwriter James Ingram topped the charts in the ‘80s with hits like “Baby, Come to Me” and “Somewhere Out There.” He also co-wrote the Michael Jackson hit “P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing).” He was 66.

(Stefano Paltera / AP) 30/33

Emmy Award-winning writer Bob Einstein was best known as stuntman Super Dave Osborne, whose feats always went wrong. The comedy veteran got his start writing for 1970s variety shows such as “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” and he later played Larry David’s devout friend Marty Funkhouser on HBO’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” He was 76.

(Archive Photos / Getty Images) 31/33

Carol Channing was a Broadway star best known for her enduring portrayal of the title character in the musical “Hello, Dolly!” A winner of three Tony Awards, including one for lifetime achievement, she appeared in the play at least 5,000 times. She was 97.

(Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images / Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images) 32/33

Mary Oliver, one of the country’s most popular poets, focused on spirituality, nature and New England. Her poems won the Pulitzer Prize in 1984 and the National Book Award in 1992. She was 83.

(Josh Reynolds / For the Times) 33/33

Herb Kelleher built Southwest Airlines into the biggest discount carrier and set the standard for budget air travel for more than three decades. He and co-founder Rollin King used a formula of short, no-frills trips that spawned dozens of imitators. He was 87.

(Ed Betz / AP) Suggs was equally inventive when it came to the fabrication of his works.

When he was working on his “Patrimony / Matrimony” series, circular tondos that explored the use of color in historic paintings, he enlisted the help of sculptor Ross Rudel to help build a contraption that would allow him to better paint circles. This consisted of a Lazy Susan-style base, on which the canvas would rotate, while he would hover over it with a paint brush (like a human record player).

“I remember scratching my head,” says Rudel. “I was like, ‘You’re going to do what?’”

“He had a large cantilevered bed, with his head dangling over, and this support for his head,” he recalls. “And a tray with dozens of mixed paints that were in order and calculated perfectly for how they would merge and expand. These took hours of planning.”

Rudel, Suggs and Stark shared a studio for years. That space, like Suggs’ classroom, was a site of mutual support.

“Generosity was core to Don’s being,” says Stark. “In 2011, when I had broken my ankle and was unable to paint, he set me up in a padded chair and made a drawing table that rested on the arms of the chair, so I could start drawing.

“I will sorely miss our honest and enlightening studio conversations,” she adds.

His legacy, says Meg Linton, a curator who helped organize the show at Ben Maltz, will extend well beyond Los Angeles.

“He’s important for the artwork he made,” she says. “But also for his connection with hundreds of artists that are now dispersed around the world through his teaching at UCLA.”

Suggs is survived by Stark and a sister, Carol Ambrosia.