Commentary: L.A. needs a summer music festival. Piano Spheres and Monday Evening Concerts show the way

Summer in the city, classically speaking, is pretty much owned by the Hollywood Bowl. The once wonderful Los Angeles Festival, last mounted in 1993, is ancient history. There remains no word on a promised Music Center international festival. But an ad-hoc, quintessentially L.A. music festival just might have begun percolating downtown.

For the first time, two venerable, venturesome L.A. concert series, Piano Spheres and Monday Evening Concerts, dipped their toes into the summer concert waters with what felt like festival-ish programming. REDCAT is hosting its annual New Original Works series, a three-weekend workshop for emerging and mid-career artists that continues until Aug. 10. And the new music ensemble wasteLAnd has begun a Summer Academy of Composition, which culminates in concerts Sunday and Aug. 10 in the Chinatown gallery Automata.

The Piano Spheres event Saturday night in its usual venue, the Colburn School’s Zipper Hall, could be looked at as a kind of coda celebration to the series’ 25th season but was, in fact, the start of something new, a jazz sideline. Concluding the season of probing L.A. pianists was Mike Lang.

He is the kind of pianist you will find nowhere else. Like the original Piano Spheres crew, he was a student of the series’ founder, Leonard Stein, who had been an assistant of Arnold Schoenberg when he taught at UCLA in the 1930s. Though a generation removed from the Schoenberg students such as David Raksin (of “Laura” fame) and Leonard Rosenman (of “Barry Lyndon” fame) who went to heap sophistication upon Hollywood film music, Lang reminds us of the seldom recognized but significant intersection between contemporary music and Hollywood.

Mt. Wilson Observatory inaugurates its Cosmic Sounds series with artist Jeff Talman’s evocation of how the universe was made.

His day job has long been as a studio musician who can be heard on, his bio noted, more than 2,000 film and television scores or recordings. He has accompanied Ella Fitzgerald and John Lennon. He was Henry Mancini’s go-to pianist. He has led his own jazz trio. Yet he also calls himself a new-music junkie who has performed at the Monday Evening Concerts and been on the board and advisory committee of Piano Spheres.

But he is also one of L.A.’s great known unknowns, a pianist and composer who doesn’t often get the spotlight. Joined by two other versatile musicians, Michael Valerio on bass and Jim Keltner on drums, Lang offered on Saturday a survey of what he called the Great American Song Book. It was, more accurately, an illumination of the Great Hollywood Song Book.

First came a short atonal improvisation, just because, Lang explained. Much of the evening was in tribute to jazz and film composers he had worked with or admired. But front and center was Mancini, who seems to be having a moment. Over the last two weeks at the Bowl, Gustavo Dudamel conducted the theme from “Peter Gunn” with such vivacity it seemed to capture the soul of an era, and John Adams coincidentally included a nod to “Gunn” in his recent piano concerto “Why Must the Devil Get All the Best Tunes?” Then there is that other Lang — Lang Lang, who recorded Mancini’s “Moon River” three years ago.

Mike Lang’s style is to seldom give you much of the tune at first. He dances around it. His chords are lushly colored with extra notes he would not know if he didn’t know atonality. His improvisations are wanders through thickets, not lost but absorbed in the harmonic brush, picking up whatever is available. One thing will remind him of something else, finding relationships where others wouldn’t.

He introduced numbers telling stories about life in the film sessions, what it was like to work with Mancini and Jerry Goldsmith, which is catnip to musical Angelenos. Mancini’s “Days of Wine and Roses” and a startlingly emotional “Moment to Moment” demonstrated the meaningful potential of chords let loose.

Elsewhere, Lang found hidden melodic cores in Bill Evans’ “Peace Piece” and Miles Davis’ “Flamenco Sketches” and hidden harmonic ones underlying Charlie Parker’s “Bird of Paradise” and Jerome Kern’s “All the Things You Are.” The revelation here, time and again, was hearing our city’s musical identity lie in a single (or a trio’s) voice. The packed hall seemed equally divided between jazz buffs and new music aficionados, both at home.

The Schoenberg connection also included the Monday Evening Concerts, in which the composer had participated. And it just so happened that in a concert at Hauser & Wirth held in conjunction with a Guillermo Kuitca exhibition, Schoenberg’s influence was at the center.

The sign in front of the Arts District gallery said both the 7 and 9 p.m. performances had sold out. The crowd once again was mixed — new music and art world. The gallery was flooded with music-related art. A series of Kuitca’s paintings of concert venues includes a brush-stroked Hollywood Bowl mistily overgrown by greenery with blue oceanic turmoil by the stage. A second exhibition of work by David Hammons was inspired by jazz great Ornette Coleman.

MEC stuck with Kuitca, a Wagner obsessive. Though not in the Hauser & Wirth exhibition, one series of Kuitca canvases increasingly blurs the album jacket of a recording of Wagner’s “Ring” cycle. This led to the starting place for the concert program, the prelude to “Tristan und Isolde,” played on a harmonium by Piano Spheres member Vicki Ray. The harmonium, a favorite instrument of Wagner’s, is powered by foot pedals. When heard close up in a corner of the gallery, it helped to remind a listener of just how radical this harmonically unsettled music was in 1865.

Schoenberg’s string sextet, “Transfigured Night,” was the next big step in musical uncertainty 35 years later. A heralding of atonality, it got a terrific performance, again for a small audience, its dissonances strikingly in our faces.

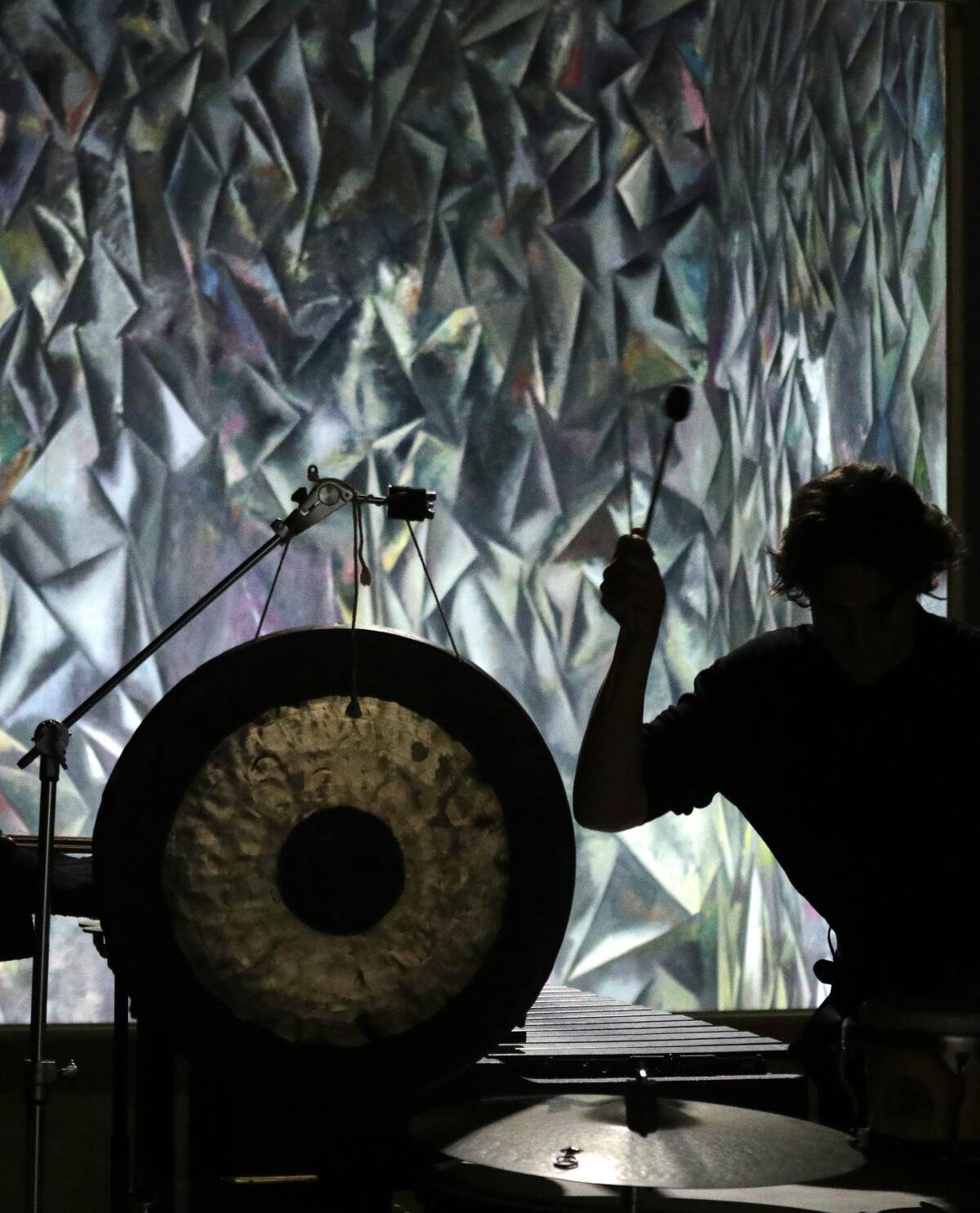

The atmosphere was one thing, but so was the intent of percussionist and MEC artistic director Jonathan Hepfer, who interspersed these works with shocking short percussion pieces by the contemporary German composer Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf. Just as Kuitca smeared the old with paint, Mahnkopf accomplished the same with sound.

In a final gallery, in front of Kuitca’s “Retablo,” its abstract design weirdly reminiscent of the style of Schoenberg’s paintings, Hepfer further brought German music up to date. Stockhausen’s groundbreaking four-channel 1956 tape work, “Gesang der Jünglinge” (Song of the Youth), with its electronic harmonic waves and haunting boy’s voice, was followed by Hepfer’s riveting performance of Helmut Lachenmann’s percussion solo, “Intérieur I,” written a decade later.

It felt unfortunate to wander out afterward into the increasingly unimaginative and barely hangout-worthy Arts District. This kind of programming is the stuff of a summer festival. And this is a city that wants one. Or how about two?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.