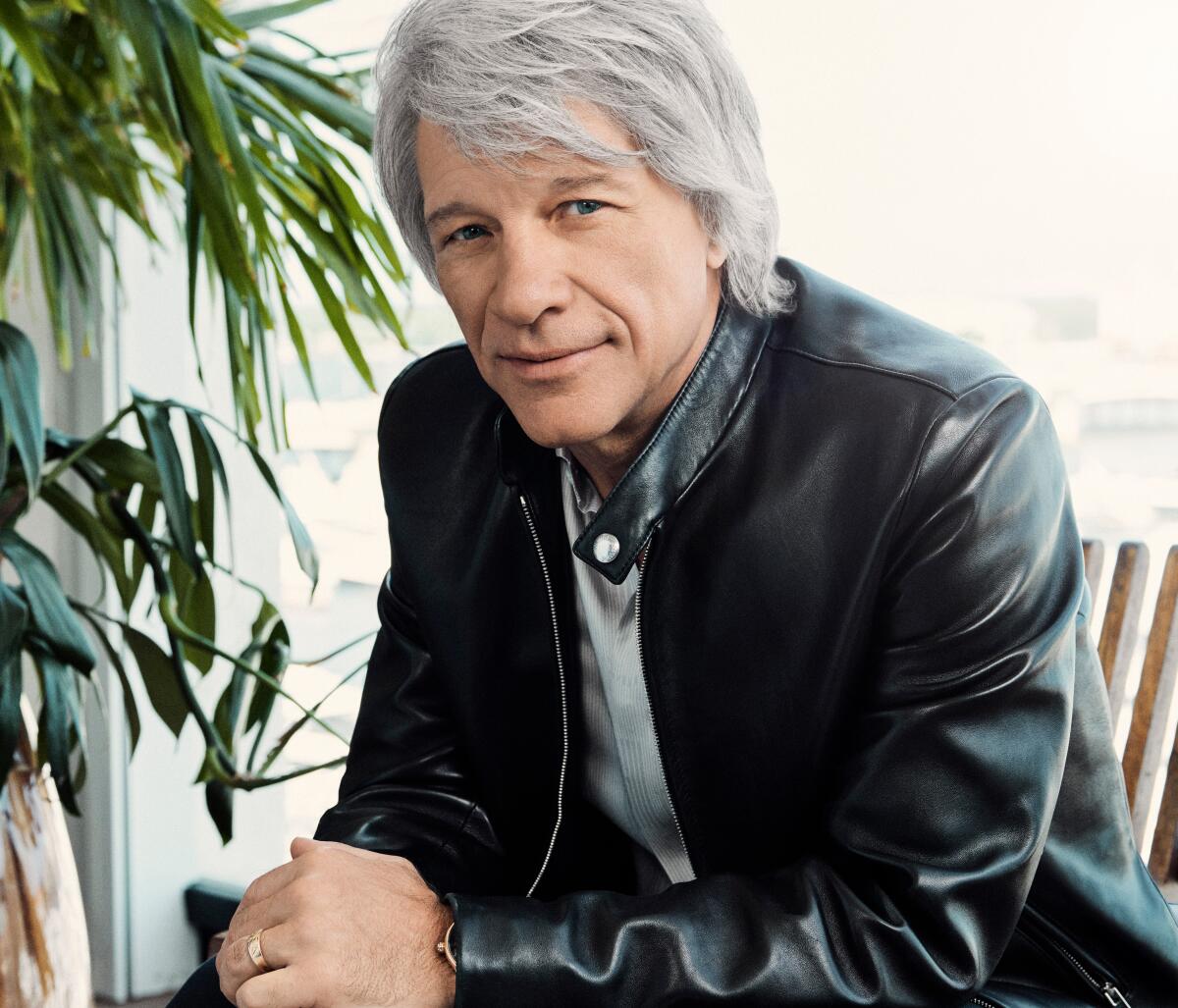

Jon Bon Jovi on Hollywood, Biden and getting ‘punched in the nose’ by a new docuseries

In early 1984, Bon Jovi emerged from the wilds of New Jersey to make its first appearance on Billboard’s Hot 100 with “Runaway,” a synthed-up pop-metal jam that frontman Jon Bon Jovi essentially willed to success by badgering a Long Island disc jockey to spin it on his air.

Forty years later, you never have to wait too long to hear Bon Jovi on the radio.

Thanks to inescapable hits like “You Give Love a Bad Name,” “Wanted Dead or Alive” and the whoa-oh-ing “Livin’ on a Prayer,” the band has sold more than 100 million records and played virtually every arena (and many of the stadiums) on the planet; in 2009, Jon Bon Jovi and his longtime creative partner, guitarist Richie Sambora, were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and in 2018 the group joined the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Now the band is recounting how it all happened in a four-part docuseries premiering Friday on Hulu. Directed by Gotham Chopra (son of the wellness icon Deepak Chopra), “Thank You, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story” covers the expected high points of the group’s ascent, including all those poufy-haired videos on MTV and Jon Bon Jovi’s turn as a Hollywood heartthrob. But it also goes behind the scenes to explore the singer’s unconventional takeover of the band’s business affairs in the early ’90s, Sambora’s departure in 2013 and Jon Bon Jovi’s recent surgery to correct a problem with his vocal cords.

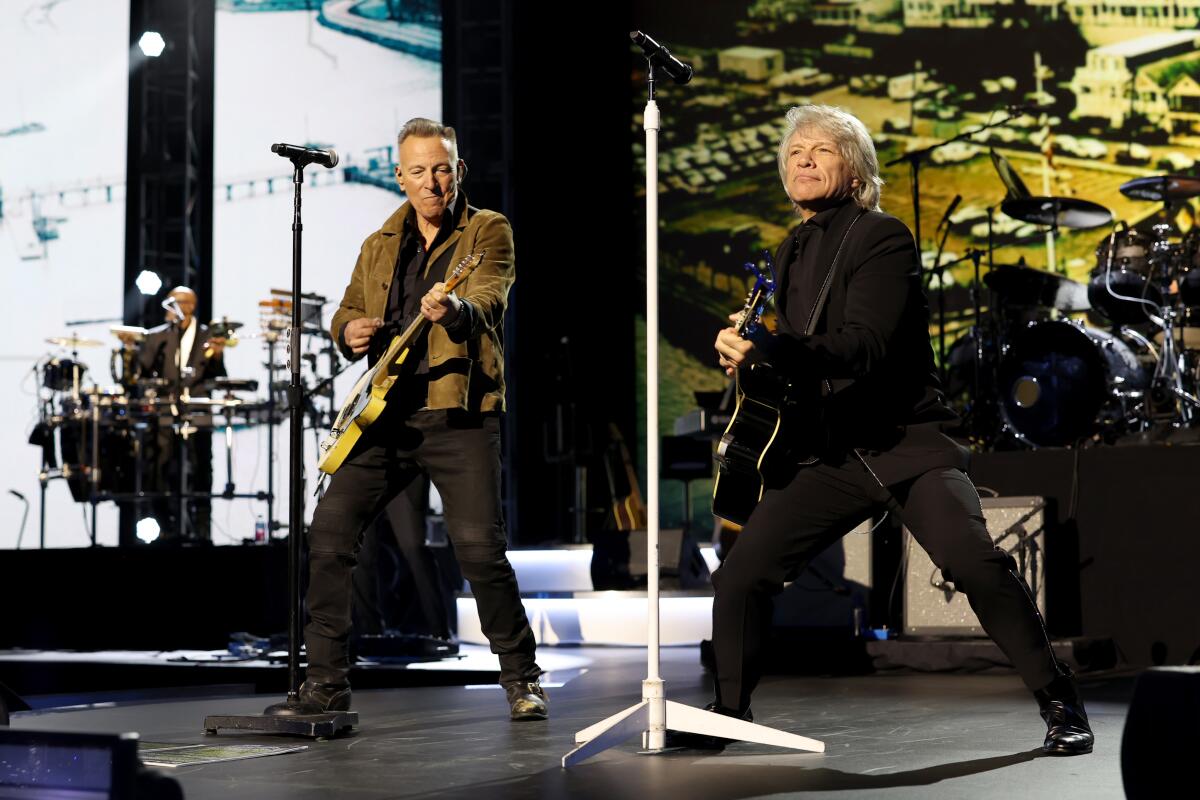

The 62-year-old frontman spoke about the series during a recent visit to Los Angeles, not long after the band performed for the first time since 2022 — and with an appearance by Bruce Springsteen — when Jon Bon Jovi was honored as MusiCares’ Person of the Year. The group will release a new album, “Forever,” on June 7.

Why did you want to do this documentary?

To mark that milestone of 40 years. I started thinking about it in Year 38 and thought, Who knows if there’ll be a 50th? Let’s mark this one. I’d seen “Man in the Arena,” Tom Brady’s docuseries, and I said, Who made this? He had an interesting take. Then I realized it was Deepak’s son. He was my first and only choice.

I assume Brady is a friend of yours.

I’d like to think that I could call him my friend.

How does the guy in that doc compare to the dude you know?

Oh, it’s Tommy. What I love about him is his work ethic. My philosophy is similar to his in that every day I’m aspiring to be a better version of me. I don’t ever want to be the fat Elvis. So Tommy was always someone I looked up to even though he’s 15, 16 years younger than me.

You call him Tommy.

I do. I don’t know if anyone else does.

Swift’s 11th studio LP, ‘The Tortured Poets Department,’ released at midnight Eastern time, follows a busy period in the 34-year-old’s personal and professional spheres.

Do people call you JBJ?

[Matthew] McConaughey started that. I love it.

Seems important that the subject of a documentary not be the person in control of it.

I have nothing to hide. If I got punched in the nose by band members in the film, the sting puts you back on your heels and then you come out of it and you go, “I understand that.” So I lived with some of that, and I’m good with it. There’s a lot of warts in this film — things I might not even agree with, where one of the guys said they didn’t know if I was coming back [after starting a solo career]. I don’t know how you could say I wasn’t coming back — I’m the guy whose name is on the marquee. But I can live with all the truths in this picture. And I can promise you I didn’t take any of it out.

If Richie hadn’t agreed to be interviewed for the series, do you think you still could’ve done it?

Certainly.

I kind of think not.

Why?

His voice seems crucial to the viewer’s understanding of the deal between the two of you.

As he says in the trailer, “I quit. I f—ed up.” We were in Calgary and he didn’t make it. I mean, car in the driveway, plane on the runway, suitcase in the trunk. We had a show that night. And this was the third time, not the first or second. We needed him to go to rehab again and he wouldn’t go. But it wasn’t like, “You’re out.” He was never fired. These were my brothers.

Do you know if Richie’s seen the doc?

He came to watch it at my house in September. We screened it together.

What was that like?

Great. There’s no animus. It’s 11 years ago.

Is he in a good place?

Yeah, he’s writing and recording.

Have you listened to his solo stuff?

I haven’t heard it.

Is the door open for him if he ever chooses to return?

The door’s always open. There was never a fight — I keep saying that.

So these are your brothers. Yet, as you say, it’s your name on the marquee. How would you define Bon Jovi’s power structure?

It’s a benevolent dictatorship. I’m the quarterback. It’s my vision — always was. It’s my record deal. The band were hired. Richie didn’t even take an integral role in the songwriting until the third album.

People in the band ever get salty about that arrangement?

If they did, they didn’t tell me. But in retrospect everybody knows we had to have a vision. Somebody had to be the one to finally say, “I think we go this way.” You know, it was pretty f—ed-up for me to say, “I’m gonna manage the band.” The industry here in Los Angeles — everybody except me and our attorney — they said, “That’s career suicide.” But it wasn’t.

The veteran jam band took advantage of the venue’s cutting-edge technology while keeping the focus on its music and its community.

How old were you when you took over?

30.

Pretty young.

Stupid. But it was great. I took it as far as I could, then it ran out and I couldn’t go any further.

Would your current manager, Irving Azoff, say you’d been an effective steward of your career?

I hope so. But what Irving said to me was, “You’re an island.” And I completely heard that. Even though I’ve been going through health issues, he’s like, “That’s cool — go out when you want to go.” With all due respect to [Bon Jovi’s first manager, Doc] McGhee, when I was a kid our organization would just push us back out on the road. What I would tell a young band today is, “Take your time if you’re tired.” Kids talk now about mental health days. No such thing 35 years ago.

In the doc we see a lot of consternation about losing your voice. But one thing you’ve been fortunate not to lose is your hair.

It’s all mine, bubba.

Has losing it ever been a fear?

Please don’t shallow yourself by making this a hair article. I’ve way superseded all that nonsense.

My point is the fear bound up in vanity.

I’m proud that I have no vanity in my hair or Botox or plastic surgery or a boob job at this point.

No work at all?

None. This is me. Who the f— is brave enough to go gray at 50? Ask Bruce, OK? Ask Bono. Ask Mick Jagger or Paul McCartney.

Speaking of which: Beatles or Stones?

Tough question. My admiration for the Beatles’ songwriting and production — it’s still otherworldly. On the other hand, Jagger’s the greatest frontman — he’s the bar. I always say I wish he’d retire because then I’d know where the end zone is. I love the Rolling Stones. But we were more Beatles.

I’d agree with that. One reason why is that Bon Jovi never seemed leering in the way that some of your ’80s hair-metal contemporaries did. It always seemed like you were trying to—

I wasn’t trying to be anything. I was only ever trying to be us. How that was perceived was everyone else’s business.

So you’re just not a leering guy.

I’m not a leering guy.

Were you a partying guy?

Define partying. Drinking? Sure. No drugs — never interested.

Because you’d seen too many cautionary tales?

No constitution for it. And the cautionary tales. But it was more that the singer had to go home because he had work tomorrow. This was my job and my joy. Why would I ever want to f— it up for an old cliché?

How’s the voice at the moment?

Work in progress. I’m an athlete coming back from an injury — Kobe Bryant with his Achilles torn off. Before I got on the plane this morning I was at vocal therapy. The goal is 2½ hours a night, four nights a week. I’m not ready to say we’re going on the road.

From Paris Hilton playing cornhole at Vampire Weekend’s set to No Doubt’s reunion, these are the best things our team saw at Coachella 2024.

You sounded strong at MusiCares.

Morning after that I woke up, first time in a decade that the only voice in my head was mine. Fear wasn’t there; doubt wasn’t there. I went, Hey, that was good. And it was fun. My wife texted the kids — she said, “He’s back.” And we don’t bulls— each other. So it’s promising.

You talk to Springsteen about your vocal trouble?

Most definitely. He’s one of my closest friends. He’d pick me up and we’d take these drives and he’d be that shoulder to lean on. Then he got sick. But it wasn’t his vocal cords. He had an ulcer.

He’s said he didn’t know if he’d sing again. Did you ever think that was a possibility?

I was more concerned for his health than for his singing. Because he’s just a robot — he can just do it. He’s never warmed up. He’s never taken a lesson. He thinks his wife [Patti Scialfa] and I are cuckoos because she does the same things I do. He’s like, “Both of you, I don’t get.”

A good number of the performers who saluted you at MusiCares were country acts: Jelly Roll, Lainey Wilson, the War and Treaty.

Modern country learned a lot from Bon Jovi records, not from Willie and Waylon and Kris. They’re more influenced by us than they were by the country standards.

You had a minute when you were making country music yourself.

When we wrote “Who Says You Can’t Go Home,” Luke Lewis, who had the label Lost Highway, he said, “I think if you do that song with Jennifer Nettles, you can get on country radio.” Great idea — No. 1 song. Then we went, “These are the stories that we tell. We could do this all day long.” And we recorded the “Lost Highway” album. But country radio really only lets you in once. Kid Rock will tell you that; Sheryl Crow will tell you that. We learned that lesson too. But I felt very comfortable in that environment, so we still record albums in Nashville. Now we’re opening a bar down there — opens next month on Broadway.

Lot of competition on Broadway right now. Garth Brooks just opened a spot. So did Eric Church.

I heard Morgan Wallen threw a chair off it.

You ever throw a chair off anything?

Not a six-story building.

There’s a clip in the doc from an episode of “Siskel & Ebert” in the ’90s where Siskel is very enthusiastic about your move into acting. Was that gratifying?

I studied for two years before I even went on an audition. And I had too much respect for the craft to ever think that I could get a role in a movie just because I was the singer in a rock band. So when I started to pursue acting, it was with all earnestness. I knew I was asking Mr. Producer to bet on me instead of fill-in-the-blank big actor.

And I did get a lot of good notices in the film business. But when I came out here [to L.A.] and said, “Why aren’t I getting bigger roles?” they said, “Because whenever you come, you show up for a minute and then you go on the road again. You’re not taking it serious.” Back then you didn’t get to do both. Will Smith had to choose. LL Cool J had to choose. Ice-T had to choose. Phil Collins, Madonna, Sting — you weren’t allowed. Then the caliber of the roles got lesser and lesser to the point where I wasn’t interested in doing it.

I remember sitting on the curb outside the old CAA building and shedding a tear after watching one of the piece-of-s— movies I was getting at that point because I wasn’t playing the game. That’s when I realized you have to commit like you do to making records.

What was the movie?

A National Lampoon movie called “Pucked” [in 2006]. F—ing horrible hockey movie. It was heartbreaking. Earlier, when I was on the set of [2000’s] “U-571,” [film producer] Dino De Laurentiis is going, “You’re a movie star.” I’m like, OK, let’s go. But then right out of that we wrote “It’s My Life.”

You’re saying you chose music.

Easy.

Jelly Roll is not your typical country star: His past includes prison, addiction and 20-plus records as a rapper. Now, he’s a favorite for multiple Grammy noms.

“It’s My Life” has always felt to me like a pivot point for Bon Jovi — a rebirth or a reintroduction.

It was one of the defining moments in our career. I had come home from making “U-571” — that was the movie where McConaughey dubbed me JBJ — and we had most of the “Crush” album written. Bruce Fairbairn was gonna come back and produce it. I literally walked in the house, the phone rang, I picked it up — still had my coat on — to find that Bruce had passed away. I was so shocked and dismayed. But then we had the opportunity to work with a young Max Martin, who flew from Sweden to New Jersey. I had this lyric: “Like Frankie said, ‘I did it my way.’” And Max, God bless him, came up with the riff.

He was in the middle of his run with Britney Spears and Backstreet Boys. Does “It’s My Life” sound different to you than any of Bon Jovi’s other monster hits?

I think it still tells that optimistic story. People said, “Who’s Frankie?” That was me going, “I want to make movies and make records and I want to be involved in politics and social issues.”

People heard that song and didn’t understand you were talking about Sinatra?

Nobody knew. They just thought we created another character like Tommy and Gina [from “Livin’ on a Prayer”]. In fact, I had to fight for that line with Richie. He was like, “Who gives a s— about Sinatra?” I go, “I do.” He says, “Well, you got to sing it every night.”

Do you plan to campaign for Joe Biden?

I don’t have any plan. But if called upon I’m here to serve.

You think he’s the man for the job?

I think the president has done a good job. It’s gonna be a tough election. There’s issues on both sides of the aisle — not a lot to be proud of in the House right now.

Is Biden too old to serve a second term?

I’m not getting into this with you [laughs]. Go f— yourself.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.