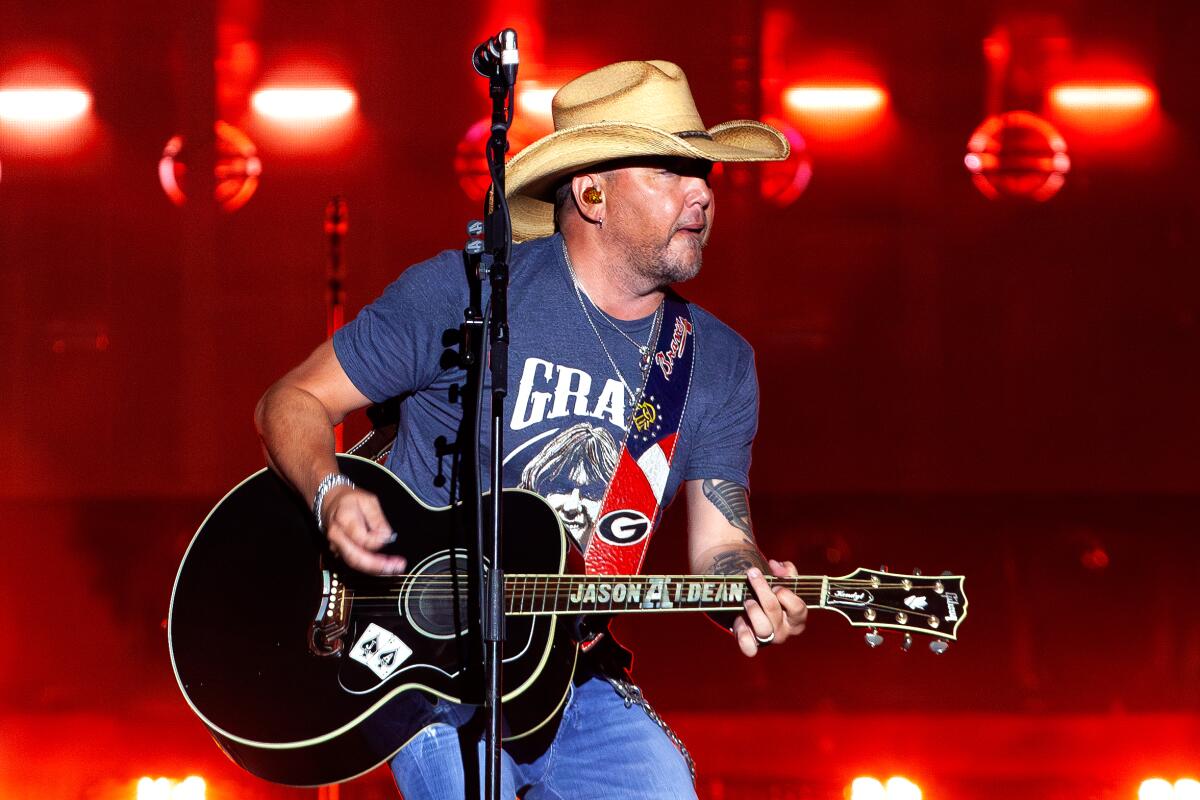

Jason Aldean on white privilege, Maren Morris, his new album and ‘very cool’ Donald Trump

NASHVILLE — It’s empty inside E3 Chophouse a few hours before dinner service on a recent afternoon, but outside the blare of passing police cars keeps interrupting Jason Aldean as he sits on the restaurant’s rooftop patio.

“I swear, it’s nonstop every time I’m up here,” says the 46-year-old country star, a co-owner of E3 with fellow singer Luke Bryan and former pro baseball player Adam LaRoche. The eatery serves steaks from LaRoche’s family ranch, though Aldean says the best thing on the menu is the lobster mac and cheese.

“We’ve got some other stuff that I was like, ‘I don’t know if people will eat that,’” he adds. “Bacon-wrapped dates? I never ate a date in my life until we opened this restaurant.” He laughs. “Not bad.”

Nashville has grown dramatically since Aldean moved here in 1998 from his native Macon, Ga. High-rise buildings seem to go up every day in the city’s increasingly crowded downtown, where Aldean has another restaurant on the ever-bustling Broadway. The sound of country music has changed too, thanks in part to Aldean, who helped introduce bruising rock guitars and slick hip-hop beats to the genre as a giant of the bro-country movement. To listen today to the singer’s 2010 smash “Dirt Road Anthem,” in which he adopts a rap-like flow, is to hear the ground being softened for the arrival of country’s current king, Morgan Wallen.

Yet Aldean is still making hits. The latest — his 28th career No. 1 on Mediabase’s country radio chart — is “Try That in a Small Town,” a twangy hard-rock number in which he issues a warning to anyone looking to bring big-city crime to a place “full of good old boys raised up right.” In July, the song even topped Billboard’s all-genre Hot 100, fueled by an enthusiastic embrace among conservatives after the “Small Town” music video — in which news footage of protesters and vandalism is projected onto a Tennessee courthouse known to historians as the site of a 1927 lynching — was banned by CMT.

Said Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis in a tweet at the time: “When the media attacks you, you’re doing something right.”

For Aldean, thrice named the Academy of Country Music’s entertainer of the year, the controversy over the “Small Town” video followed earlier episodes in which he and his wife, right-wing influencer Brittany Aldean, dressed their young children in T-shirts that read “Hidin’ From Biden” and traded barbs online with country star Maren Morris over young people seeking gender-affirming healthcare. (In September, Morris dropped a new single, “The Tree,” with a video widely interpreted as a response to “Try That in a Small Town.”)

“Small Town” appears on Aldean’s new album, “Highway Desperado,” which offers his signature mix of puffed-chest country songs and manicured power ballads. “Growing up as an ’80s kid, all the big rock bands — Bon Jovi, Def Leppard — they’d all have the one big ballad, and I think that’s kind of the mind-set when I’m doing a record,” he says, dressed in tight jeans, a plaid shirt and a ball cap emblazoned with the Georgia flag.

I ask if scoring a No. 1 hit ever gets old.

“No. This many years into my career and the fact that people still seem to be into what we’re doing — it’s a good feeling,” Aldean says. “Plus, Luke Bryan likes to hold it over my head that he’s got two more than I got. I’m trying to catch him.”

Part of the way you’ve framed “Try That in a Small Town” is that you’re saying something you’re not supposed to say. Does the song’s success undercut the idea that you’re voicing an unpopular opinion?

Saying that an opinion is unpopular — unpopular to who? That’s the thing. Us putting that song out and it doing what it’s done just shows me there’s a lot of people out there that feel the same way I feel. It’s a subject matter that over the years has been sort of taught when you’re in the entertainment industry, you stay away from those things. Which I did for a while for no other reason than I was younger and I wasn’t this tapped into politics.

Was it that or that you were coming up and didn’t have the cultural capital to spend that you’ve got now?

I’m definitely at a place in my career where I don’t have to watch every little move I make.

What’d you make of the backlash to the song and video?

It was a little surprising. I mean, I felt like the song would probably start a conversation about the state of the country. You have a lot of people sitting there watching this stuff every day on TV — laws being passed where if you own a store, people can just go in and take your stuff and you can’t do anything.

I don’t think that’s a law.

In California, you can’t stop them. [Note: Early versions of California Senate Bill 553 included a provision that would have prohibited businesses from requiring nonsecurity employees to confront shoplifters.] It’s just wild stuff that happens, and as blue-collar, hardworking people, you’re watching these things and you’re like, “What is going on?” So I thought the conversation would be: “All right, this is crazy. We need to figure this out.” Then you had people that wanted to make it something else and try to find whatever they wanted to find wrong with the song or video. I made it a point in the video to show people of all races and colors doing things that in my opinion were not cool.

The production company that made the video put out a statement that said you didn’t choose the courthouse location.

That’s a fact.

If you’d known its history, would you have shot it there?

It would have definitely been more of a conversation. But there’s been a ton of things shot there and it was never brought up. Then all of a sudden, our video comes out. People were trying to find something where there was nothing.

You sing, “Around here we take care of our own.” You don’t think someone could hear that as white people circling the wagons?

I mean, you could take it as that if that’s how you want to take it. But the way you take it, versus the way I said it and meant it, it’s not necessarily accurate. It’s a very simple message: What I see happening, I’ve never seen that in the towns I grew up in in Georgia. It just doesn’t happen, and it wouldn’t last.

The song paints a pretty hysterical portrait of urban chaos.

There’s people getting carjacked and kids getting trafficked here in Nashville. There’s s— going on. I don’t know if when you come from a bigger city, it just becomes the new normal. I mean, I don’t live here in town. I live almost an hour outside of town. I wouldn’t live in downtown Nashville at all.

Because it’s too violent?

No, no, no. But I do think in bigger cities, you have bigger problems. You’re gonna have more crime, you’re gonna have more chaos. I’m not saying it’s every major city across the country, but there are some where it gets a little wild.

After CMT banned the video, every conservative politician and pundit in the world rushed in to say, “This is my song — I’m with this guy.” What was that like?

I appreciated that they understood where I was coming from on the song. I think it resonated with middle America, working-class America.

But they’re not working-class Americans. They’re rich politicians.

Right, but that’s their base. That’s who supports them.

Jelly Roll is not your typical country star: His past includes prison, addiction and 20-plus records as a rapper. Now, he’s a favorite for multiple Grammy noms.

What was Macon like when you were a kid?

I grew up on the outskirts — more of a farm community. Went to a little school, graduated with about 40 people in my class. Everybody knew everybody. It was a normal childhood.

Macon is a racially mixed city.

I grew up playing sports with Black teammates. I grew up playing music with Black musicians. We live on this side of the track, they live on that side — it was never that kind of s—. So to act like it’s some new development for me, as I’ve gotten into adulthood, that I’m trying to learn how to interact with a different race is f—ing stupid.

Do you think systemic racism exists?

Explain.

The idea that racism is encoded into American life and American law. Essentially the opposite of white privilege.

I don’t know what it’s like to be a Black person. And I wasn’t raised to be a white person that had all these privileges. So I don’t really know how I feel about all that stuff. I can’t really speak on that.

You have to know how you feel. You’re a person living in the world.

Yeah, but I can’t speak on how Black people feel about white people. I mean, the white privilege thing — I didn’t grow up with white privilege. So I don’t know how to answer that.

You played a show at Nashville’s Bridgestone Arena amid the Maren Morris drama where you joked that she was gonna join you onstage, which led the audience to boo. What was that like for you up there?

The stuff with her is so far off my radar at this point. I’ve never talked to her for more than probably 10 seconds. So I don’t really have an opinion about her. The only thing I knew was that she was coming after my wife in the media. Obviously, her and I are on completely different ends of the spectrum as far as our beliefs. But I don’t know her at all, truly. That’s what was so weird for me: This chick’s coming after us, and I’ve never even talked to her before. Yet she claimed to know so much about me and my wife somehow.

You’ve been in Nashville for 25 years. Has the industry changed in terms of how people get along?

I think it’s like everything else you deal with in the world since politics have really bubbled to the surface for a lot of us. You have guys standing hard on this line; some stand hard on this line. So yeah, it’s changed.

There’s a generational shift happening in country music right now, from you and Eric Church and Blake Shelton — guys in your mid- to late 40s — to younger stars like Morgan Wallen and Luke Combs in their early 30s. Is that hard to go through?

Just kind of comes with the territory. But here we, 18 years in, just came off of selling out a tour. So I don’t think about it in terms of getting phased out. I love the guys that are coming up — Morgan and Luke and Parker McCollum. It’s a great crop of young artists that I think are gonna carry the torch for a long time. At some point, the fans will tell us, “OK, your days at country radio are over.” But I don’t see it happening anytime in the next couple of years.

At just 23, former gas pipeline worker Bailey Zimmerman has scored three straight No. 1 country hits. ‘I’m having a freaking blast,’ he says.

White men still dominate this next generation. Does country music over-index on straight white dudes?

Maybe? I like to think that if you’re a talented artist and your songs are good and you’re a great performer, then somebody’s gonna give you a chance, whether you’re a guy, a female, a duo, a band, whatever. Male artists seem to have dominated the genre a little bit over the last however many years. But you also have some great female acts: Carrie [Underwood] and Miranda [Lambert], and Carly Pearce is coming up now.

What do you make of the effort among people in the so-called Americana scene to create more room for women and queer people and people of color?

I just think it goes back to the talent. To me, it’s more about that than trying to make sure we get one of these and one of these.

Let’s end with a lightning round. Was Joe Biden legitimately elected president?

Depends on who you ask.

I’m asking you.

I feel like that’s just old news at this point. And regardless of if he was or wasn’t, he’s been the president for the last three years.

Do you want Donald Trump to be the Republican party’s presidential nominee?

It wouldn’t hurt my feelings. I like Trump. Hung out with him a couple times — been very cool to me. I have nothing but good things to say about the guy.

The people who’ve been jailed for taking part in the Jan. 6 insurrection — is that right or wrong?

I’m not OK with destroying property, lawlessness, rioting, any of those things. I think it was not a good look. We have law and order for a reason. If we choose to set those laws aside and do whatever we want, it’s chaos, and I’m not cool with that.

Did you get a COVID vaccine?

No. I felt like I’m a healthy guy, and this was a vaccine that Trump was pushing at the end of his office and Biden was saying, “Oh, don’t do it — it’s too soon.” Then as soon as Biden gets in: “Everybody get the shot.” [Note: In September 2020, Biden said, “I trust vaccines. I trust scientists. But I don’t trust Donald Trump. And at this point, the American people can’t, either.”] To me it was like, I don’t really know what’s going on here, so I’m just gonna stay away from it. That’s what I decided to do, and I’m very happy with my decision.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.