Joan Baez on facing trauma, her Bob Dylan epiphany and belonging to the ‘no facelift’ club

In the last 10 months, the venerable folk singer-songwriter Joan Baez has released a book of drawings, addressed the United Nations in Geneva and sang “We Shall Overcome” with state Rep. Justin Jones, a member of the so-called Tennessee Three, at the airport in Nashville. And that is but a sliver of the 82-year-old’s recent doings.

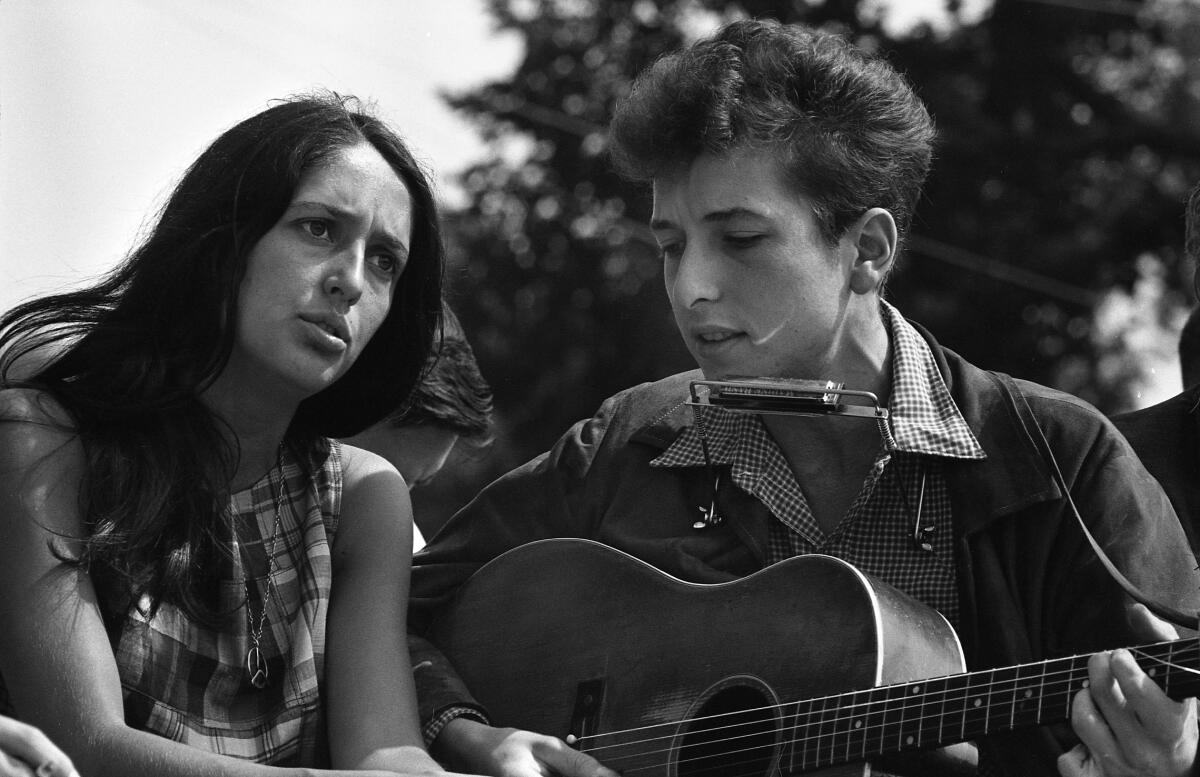

Baez’s career launched at the 1959 Newport Folk Festival about a year after she began performing at folk music clubs in Boston and Cambridge when she was just 17 years old. By 1961, she was a star. “Joan Baez, Vol. 2,” an album of traditional songs, sold hundreds of thousands of copies, as did two live albums, “Joan Baez in Concert” Parts 1 and 2. Amid her high profile in America’s folk music revival, she invited a young Bob Dylan, whom she met in 1961, to open her concerts, thus introducing him to the world. In 1965, their romantic and creative partnership ended, and Baez immortalized their relationship in her 1975 song “Diamonds & Rust.” A committed activist, Baez marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and famously performed “We Shall Overcome” at the 1963 March on Washington. She has also spoken out against the Vietnam War, the death penalty, the war in Iraq and environmental destruction, and on behalf of the LGBTQ community.

On Friday and Saturday, a new documentary about Baez, “I Am a Noise,” will screen at the Landmark Nuart Theatre in West L.A. Pop star Lana Del Rey will host Baez in conversation after the Friday showing. On a Zoom call from her home in Woodside, Calif., Baez discussed the new film, her desire to be current and why she never had a facelift.

In the film, you talk about difficult topics like trauma, abuse and aging. How was that process for you?

There were some times where I thought, “Really? I have to talk about that.” But then I’d think, this is supposed to be honest. This is my legacy. Now, each time I see the film, I see more that I didn’t know [about myself]. It’s been an emotional ride. And I am delighted with how it came out. Wrinkles and all. It’s honest.

What do you mean by seeing things that you didn’t know?

I’d never been in my own storage unit. When they filmed me going in, that’s the first time I’d ever been in it. That was not an act.

It was filled with materials you hadn’t seen before?

The old tapes with the therapist, I hadn’t visited those for decades. Now I’m trying to decide what to do with them. I’ll probably have a wonderful bonfire [laughs]. Also, my mother kept everything. All of those old tapes, I kind of remember doing them [when I was a child], but I didn’t know they still existed. My dad took Super 8s nonstop.

After finally gaining control of his Creedence Clearwater Revival catalog, John Fogerty, with help from his sons, is rediscovering the joy in his life’s work.

In the film, you say that whenever someone gets famous at a young age, they never expect that it will end. Was there a point where you thought it had ended?

When the theaters and other rooms weren’t full [in the 1980s]. I started blaming everyone else, but in fact I was drifting away. I didn’t have the machinery around me because I was anti-commercial for so long. It took a while for me to realize where I was, which was nowhere.

How did you rebound from that?

I made three beautiful albums, which I still love [“Recently,” “Diamonds and Rust in the Bullring” and “Speaking of Dreams”]. I woke up in the middle of the night during the making of the third one and thought, “Why am I doing this when I know only my family will hear it?” So I started interviewing managers. I wasn’t f—ing around at that point. I said, “I want to be relevant again.” Being a legend is a drag if you’re not also current.

The film in part follows you on your 2018 farewell tour, but it seems like you may never slow down. Will you ever truly retire?

What’s difficult for me, but I am working on, is to literally stop. When I do stop myself, I can actually look and see what’s there, the blessings and the curses. But you’re right. When the singing stopped, I just got blown out of a cannon with all of this other stuff. I just finished editing a book of poetry that will come out in the spring.

How long have you been working on that?

It’s from poems I wrote back in the ’90s, tucked all over the house. I had to go around and find them.

I think many people forget that you helped Bob Dylan with his rise. It wasn’t the other way around. How do you feel about him today?

You know, I don’t resent any of it now. One day I was painting his portrait, of when he was really young. I put his music on and I had an epiphany. I cried for about 48 hours. I thought, “Oh, my God, I was so lucky to know this guy and hear those songs and have those songs.” Bob was what, 22 or something? I was a kid too, but I had more ability to manage stuff than he had. I think that’s fair to say. But I just don’t have animosity now. I certainly did. It was awful. But that’s done now.

It’s easy to idealize the ’60s, but I wonder how it compares to today, in terms of your ability to get things done as an activist?

Back then, there was glue. We did feel that we were with somebody, that we were together. The only thing I can think of for people who didn’t live through that was when Obama was running for office. There was such a good feeling, like people high-fiving on the subway, that was the glue.

Is America worse today?

Nobody could’ve written the scenario of what’s happening now [post-Trump]. It’s deadly. It’s evil. There’s no caring. It promotes the opposite of empathy. It promotes anger and belittling and bullying. On top of that, there’s climate change, which for me is the most heartbreaking.

How do you handle climate dread?

It’s a daily process of trying to live in the moment and accept what’s still there. There’s this beautiful creek at the bottom of the hill [from my home]. I spend a lot of time down there and I keep hearing it say, “Remember me like this. Remember me as I am now.” Instead of looking at it and thinking, “Oh, my God, it’s going to be dry one day.”

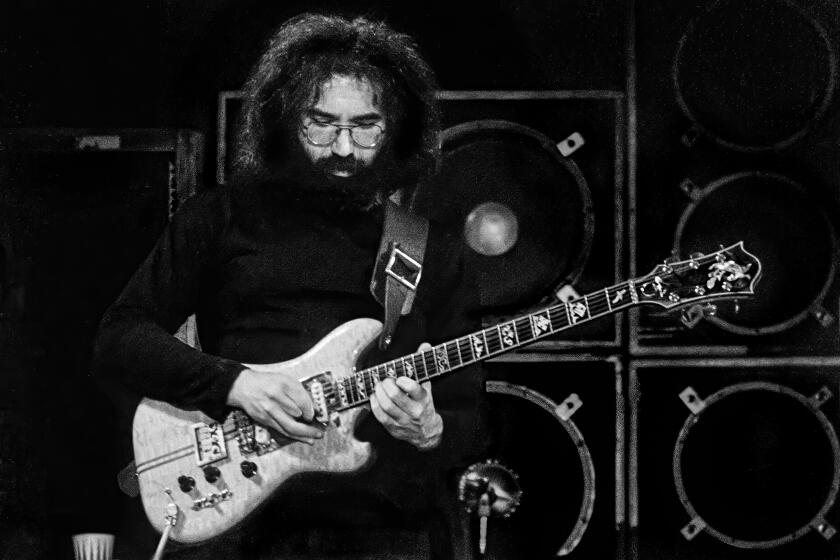

A new lineup. A new label. A new studio: Following the death of Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan, Jerry Garcia and the Dead reinvented themselves on ‘Wake of the Flood.’

Are there any young musicians today who you feel like are carrying on your legacy?

Probably Phoebe Bridgers. Her music is really nothing similar to mine. But she’s a kid who’s thoughtful and is aware of what’s going on. I feel as though she’s aware of the situation in the world and deals with it in her own way.

One aspect of the film, which feels like a kind of activism, is its emphasis on your physicality, body and face, in its natural everyday form. America has this tendency to hide aging or view it as a defect.

That’s a good point. I belong to the no facelift group. My sister Mimi used to say that her home remedy for aging was “No, no, no, no, no, no” [laughs]. But that doesn’t actually work. I’ve certainly been tempted, but I let go of the idea. I also didn’t want to look a certain way until it all drops one day like, “Here’s the real you!”

No Botox or anything?

Nope!

A lot of your friends, family and compatriots from the film have died. How does it feel to be one of the last standing?

It reminds me of my mother’s old address book. At a certain point it was nothing but chicken scratches because they were all gone. I’ve just gotta get used to the idea. I’m healthy, but you never know.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.