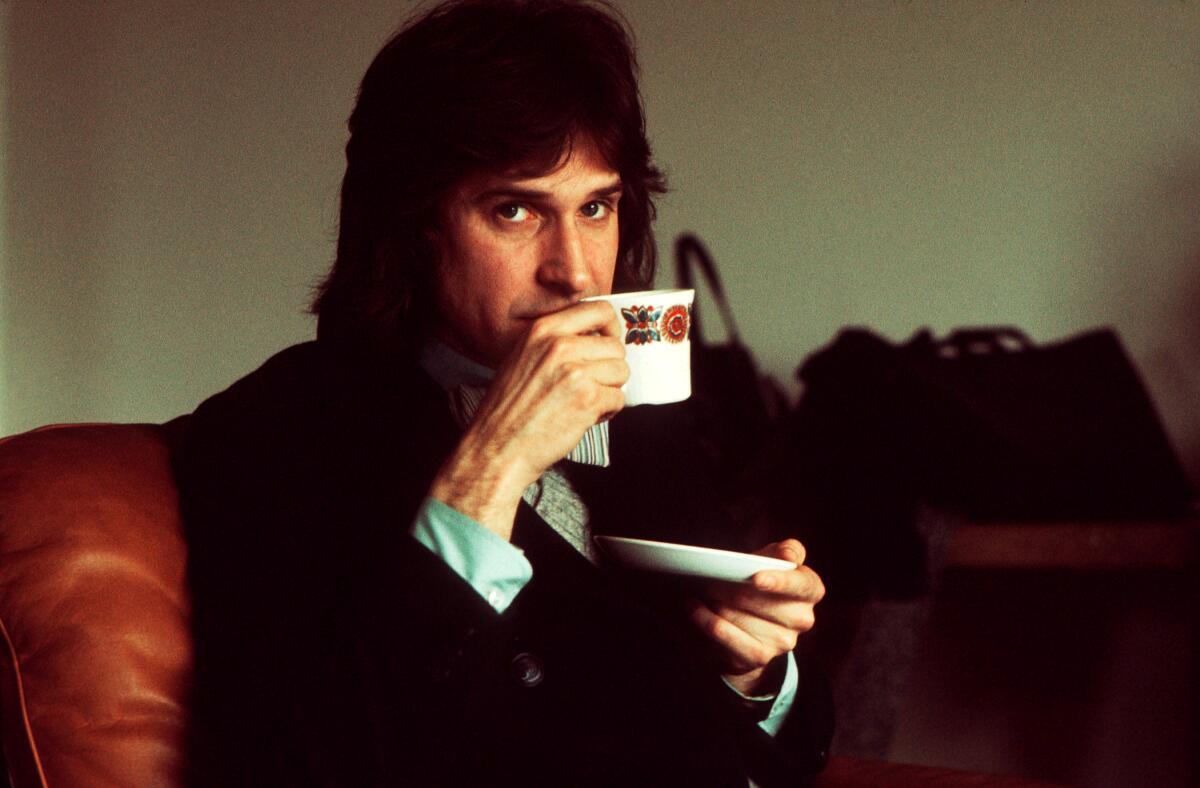

The Kinks’ Ray Davies on the song he wants played at his funeral

Since the 1980s, Ray Davies has intermittently led a seminar for aspiring songwriters through England’s Arvon Foundation — a side hustle he landed, of course, as a result of the dozens of classic tunes he penned as frontman of the Kinks, including “You Really Got Me,” “All Day and All of the Night,” “Tired of Waiting for You,” “Stop Your Sobbing,” “Sunny Afternoon,” “Waterloo Sunset,” “Lola” and “Come Dancing,” among many others.

Yet ask Davies, 78, which of these was the first to make him feel like he was a real songwriter, and he’ll tell you he’s not sure he’s one even now.

“What I usually say to the students before I start the course is, ‘I can’t teach you anything,’” he says, chuckling dryly, over Zoom from his home in the U.K. “‘Real songwriter’ gives me an image of a guy from Tin Pan Alley or the Brill Building — like Neil Sedaka. I think I’m still trying to find out if I’m that good.”

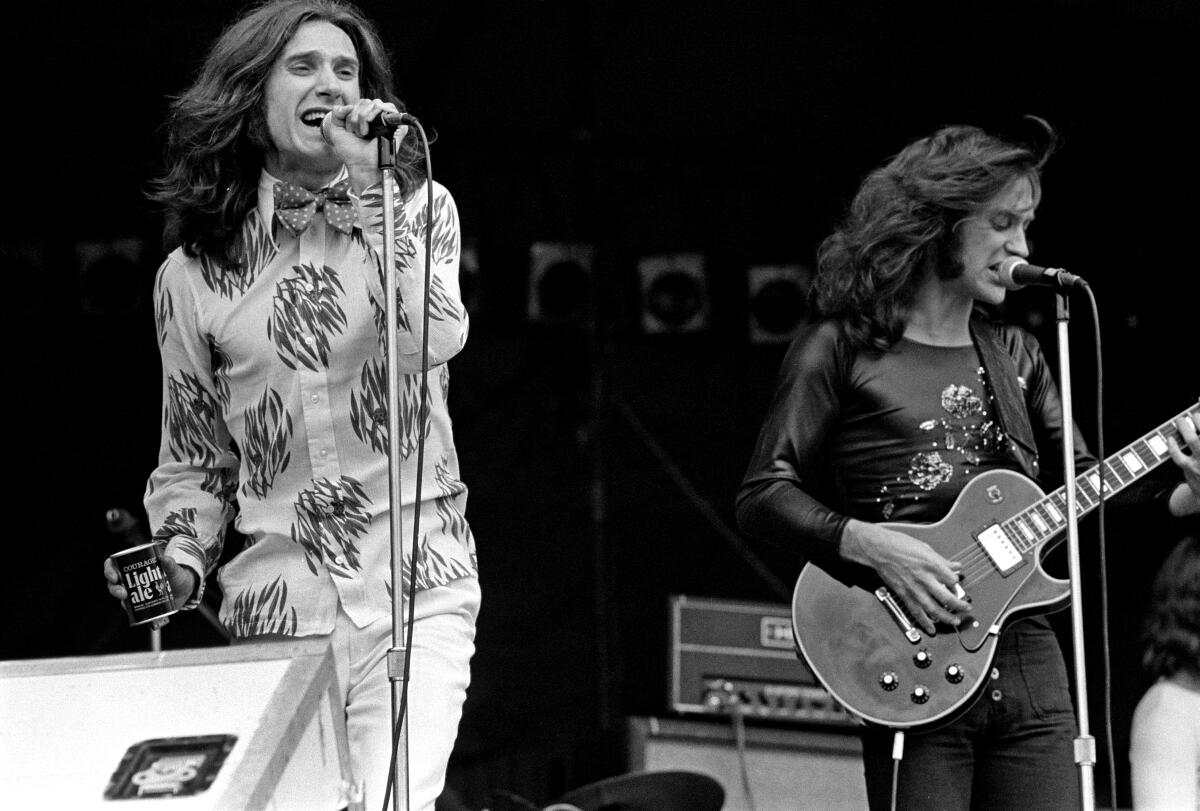

Caveat thus offered, Davies agreed to look back at — and to classify — some of the high points of his career with the Kinks, which he formed in 1963 with his younger brother Dave Davies on guitar and which became one of the key acts of the British Invasion (at least until they were temporarily banned from entering the U.S. in 1965 amid a dispute with the American musicians’ union).

Though never as popular as the Beatles or the Rolling Stones, the Kinks covered no less musical ground, blending elements of rock, folk, pop, country, R&B and British music hall in detailed songs about the lives of English people; the band, rounded out at the beginning by drummer Mick Avory and bassist Pete Quaife, also helped lay the groundwork for garage rock and heavy metal, thanks in large part to Dave’s blistering guitar work. Among their punk successors were the Buzzcocks and most famously the Jam; later inheritors include Yo La Tengo, Fountains of Wayne and any number of acts associated with the Britpop movement of the mid-1990s.

The Kinks, who broke up in 1996 but who seem always on the verge of reuniting, collect 36 of their songs on a new compilation titled “The Journey — Part 1.” A second volume is due later this year.

Superstars Taylor Swift, Drake, and Beyoncé head up a far-ranging slate of concerts this summer.

The most British song in the Kinks’ catalog: “A Well Respected Man” (1965)

In an era when many of his peers had their sights set on America, Davies wrote with remarkable sympathy about working-class Brits — about their goals and their resentments and about the sometimes-crushing weight of the country’s traditions. “While lots of bands sang in American accents, we were singing in London accents,” he says. He could also rail against the U.K.’s upper crust, as in this crisp but savage portrait of a privileged guy eager to “grab his father’s loot when pater passes on.”

The song that makes Davies think of his mother: “Waterloo Sunset” (1967)

“Unlike many other rockers, I always cared what my parents thought of my music,” says Davies, who adds that, even as a younger man, “I was writing songs for older people.” He recalls playing “Waterloo Sunset” — a gently psychedelic pop tune in which the narrator watches two lovers cross a bridge over the River Thames — for his mother and his older sister Rose and being buoyed by their enthusiasm. The song, which paints a modest scene in almost unbearably pretty colors, “says a lot about people of [my mother’s] postwar generation living in austerity in London. I was a strange kid, not very sociable, but I think with this song she finally understood me a bit.”

The song that makes him think of his father: “Alcohol” (1971)

A “true Kinkophile,” the singer says, Davies’ father “would have related to this tale of the decline of a philanderer” from the Kinks’ bluesy-rootsy “Muswell Hillbillies” album, which was inspired by the North London neighborhood in which the Davies brothers grew up.

The song that most rips off one of Davies’ heroes: “So Mystifying” (1964)

To Davies’ ears, this propulsive cut from the Kinks’ self-titled debut makes clear the debt he and his brother owed Chuck Berry, whom he calls “one of the underrated poets in American culture.”

The most depressing song he ever wrote: “Dead End Street” (1966)

“What are we living for? / Two-roomed apartment on the second floor,” Davies sings in this stark hard-times lament. “Yet it’s not actually meant to be depressing,” he clarifies, adding that he thinks of the song as “musical journalism: You’re conveying the bleakness of a real situation through an art form.”

The most misanthropic song he ever wrote: “20th Century Man” (1971)

Davies came up with “Muswell Hillbillies’” stomping opener — “I’m a 20th century man but I don’t wanna die here,” he sings — while pondering the “breakdown of community,” as he puts it, that led to London’s bombardment during World War II. “Communities are still breaking down now but for other reasons,” he says. “You go into a restaurant expecting to see people having dinner with one another and they’re all looking at their iPhones.” He laughs. “That’s me being a bit grumpy.”

The best riff Davies ever created: “You Really Got Me” (1964)

“Gotta be that one, right?” he says of the indelible two-note figure — composed by Ray on piano before Dave brought it to guitar — that not only took the Kinks to No. 1 on the British singles chart but also launched the career of Van Halen when the L.A. band covered “You Really Got Me” a decade and a half later.

The easiest song he ever wrote: “You Really Got Me” (1964)

“As a songwriter, I’d probably write more lyrics today,” Davies says. “What’s it saying? She’s really got him going, and he’s crazy about her. Very unsubtle in many respects. But that’s the whole point. I didn’t think about the lyrics. I just made them up and sang them.”

The song he never expected to become a hit: “Tired of Waiting for You” (1965)

Davies remembers having a severe chest cold the day he recorded the vocal for this wistful chart-topper. “So I went in thinking I’d just satisfy the commitment to the record label,” he says. “But I’m pleased with the performance, don’t get me wrong. If I’d tried too hard, maybe it would’ve gone over the top.”

The song he thought would be a hit but wasn’t: “Ev’rybody’s Gonna Be Happy” (1965)

The Kinks modeled this spirited dance number on the music of Motown’s house band, the Funk Brothers, and in particular the intricate drumming of Uriel Jones, who’d become friendly with the Kinks’ Avory. “I told Mick it should be written around this drum pattern like Uriel would do,” Davies says. “He could somehow make a drum part into a hook. So we tried to get Mick to do it, but he couldn’t.” The single, released as the follow-up to “Tired of Waiting for You,” stalled out at No. 17 on the British chart. Says Davies: “Maybe it was too intricate a pattern for rock ’n’ roll. It’s not Mick’s fault — I wrote the bloody song.”

The cover of a Kinks song he loves the most: Peggy Lee’s “I Go to Sleep” (1965)

Davies likes Van Halen’s take on “You Really Got Me,” and he admires “Stop Your Sobbing” by the Pretenders, whose Chrissie Hynde he went on to have a child with. His favorite cover of one of his tunes, though, is Lee’s jazzy version of “I Go to Sleep,” which “made me feel kind of warm inside,” he says, not least because it impressed one of his sisters, who was a huge fan of the pre-rock pop star.

The song he’d like played at his funeral: “Days” (1968)

“Thank you for the days, those endless days / Those sacred days you gave me,” Davies sings in this chiming farewell that he wrote for (but ultimately cut from) the first of the Kinks’ several concept albums, “The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society.” “But that’s only if I have to pick one of my songs,” he says. “If not, I choose ‘SOS’ by ABBA.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.