Mars Volta’s lead singer broke with Scientology and reunited with the band. His battles with the church aren’t over

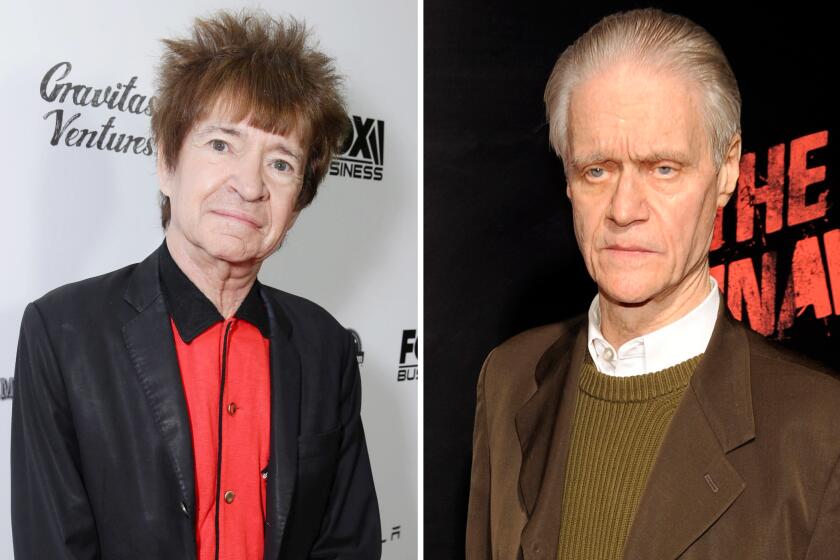

In October 2022, the Mars Volta walked onto the stage of a sold-out Hollywood Palladium for their first L.A. show in a decade. For three nights, to nearly 12,000 fans in total, the punk/prog/Latin band — with core members Cedric Bixler-Zavala, 48, and Omar Rodríguez-López, 47 — played three-hour sets of searing, heady jams.

Long lauded as one of heavy music’s most ambitious acts, they played cuts like “Inertiatic ESP” with a vicious new focus. On the sinister “Blacklight Shine,” falsetto-wailing frontman Bixler-Zavala sang in Spanish: “Karma’s slow to come / But it will come / You’re going to pay.” Then he switched to English: “Help me out of this godforsaken cure ... I’ll shine the blackest light / To the culprit on all fours.”

Many fans knew exactly where those lyrics were pointed. Scientology’s Celebrity Centre was just a mile away. The church, Bixler-Zavala claims in an interview and lawsuit, nearly destroyed his band and his family.

Bixler-Zavala began attending programs at the Church of Scientology in 2009 after his wife, Chrissie Carnell Bixler, introduced him to the organization’s tight-knit scene of actors and artists.

In 2016, Carnell Bixler alleged that “That ‘70s Show” actor Danny Masterson, a fellow Scientologist, had sexually and physically assaulted her in the early 2000s, joining two other women testifying against Masterson in his criminal trial on rape charges (a fourth joined a civil suit against him). The Bixlers allege the church then began a relentless campaign of harassment and threats against them, including poisoning their dogs, stalking and surveilling them and claiming they were “fair game” for retaliation, according to their 2019 civil suit filed against Masterson, the Church of Scientology International and its leader David Miscavige (Bixler-Zavala is also a plaintiff in the civil suit).

After a jury deadlocked last year, actor Danny Masterson is on trial for a second time on charges he raped multiple women in the early 2000s.

Masterson’s criminal case ended in a mistrial in November. Prosecutors refiled the case and a second trial began in April; if found guilty, Masterson could face 45 years to life in prison. The civil suit is set for a hearing on June 28.

Masterson pleaded not guilty to all charges in the criminal case. A spokesperson for Masterson declined to comment on the case or the allegations in the civil suit.

Scientology spokeswoman Karin Pouw said in a statement to The Times that “the scandalous allegations about the Church” contained in the Bixlers’ suit “are complete fabrications.” She denied that the Church of Scientology had anything to do with the death of the Bixlers’ dogs, and denied the harassment and surveillance allegations.

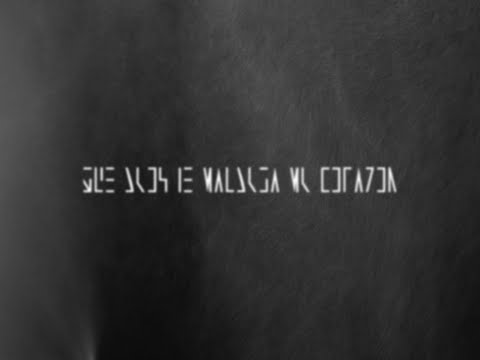

While the Bixlers await the outcome of the second trial, on April 21, the Mars Volta released its second new album in a year. “Que Dios Te Maldiga Mi Corazón” (May God Curse You My Love) is a Latin revamp of their 2022 self-titled comeback LP, pulling from the duo’s Mexican and Puerto Rican heritages and anti-colonial politics.

The band dissolved back in 2013, in part due to Bixler-Zavala’s involvement with the church (Rodríguez-López did not become a Scientologist). It took years for the longtime friends and bandmates to fully reconcile.

Describing Scientology’s role in the band’s breakup, Bixler-Zavala said, “I’ve grappled with that with great difficulty. But Omar allowed me to come back in and make amends, to own up to my past bull—. “

“It’s hard to talk about,” Rodríguez-López said, “when you love someone and worry about them like that.”

In March, Bixler-Zavala and Rodríguez-López met up at Silent Zoo Studios in Glendale to talk about “Que Dios” and the last few turbulent years. The two met growing up in El Paso but now live hundreds of miles from each other — Bixler-Zavala with his wife and children in L.A. and Rodríguez-López splitting time between his birthplace of Puerto Rico and the duo’s old hometown.

While they have an easy rapport, they rarely give interviews anymore. They still wear their longtime uniforms of all-black clothing and cascading curly hair, even if time has tempered their thrashing, downed-power-line stage presence a bit.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Rodríguez-López admits he had mixed feelings about revisiting this beloved but troubled band. “My feeling about reuniting was always ‘I’m not interested in this unless we have a purpose,’” he said. “When this thing happened with [Cedric’s] family, it was clear to me that now there’s a purpose. Now it means something beyond just playing music again.”

Bixler-Zavala wants those still involved with Scientology to find hope in his experience.

“Part of me wants to be a lighthouse in the fog,” he continued, “because there’s a lot of people who have very similar stories to ours, and they’re so afraid.”

The Mars Volta are sui generis in heavy rock. After forming in the early 2000s in the wake of their beloved post-punk band At the Drive-In, the duo turned to dizzying time signatures, tropical psychedelia, acid-dipped guitar noise and dense, freewheeling dread.

They blew away Rick Rubin, who produced their 2003 debut, “De-Loused in the Comatorium.” In the studio, they’ve recruited the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ John Frusciante and Flea and Queens of the Stone Age’s drummer Jon Theodore as backing musicians, and pop star Lizzo cites their song “Wax Simulacra” as one of her formative teenage anthems. They’ve landed three Top 10 albums and have played to stadium-size crowds.

In early 2009, the band had just wrapped up a tour for its fourth LP, “The Bedlam in Goliath,” which debuted at No. 3 on the Billboard 200. That year, Bixler-Zavala met his future wife at the Hollywood nightclub Bardot, and he soon grew curious about her unorthodox faith.

“I had seen Scientology brochures and DVDs in her apartment, so I asked her about it,” Bixler-Zavala said. “She was apprehensive about admitting it. Looking back, I could tell there was something painful there.”

He sought out the church’s counseling to kick an expensive marijuana habit. At the time, it worked.

“I did the purification and started taking courses and life-repair auditing,” he said. “I got super dogmatic, because I’d found something that worked as a higher power.”

Scientology is the global church founded by L. Ron Hubbard in the 1950s, based in Los Angeles and Clearwater, Fla. Its founding text, “Dianetics,” and Hubbard’s subsequent writings teach that humans have an immortal soul (a “thetan”) that’s been damaged by traumatic experiences (which are stored as harmful “engrams”). Through its process of “auditing,” a Scientologist can heal those wounds and, after taking courses that can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, ascend up the “Bridge to Total Freedom.”

While once powerful in Hollywood, the church’s influence waned in the 2010s after investigative books, newspaper stories and documentaries like HBO’s “Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief” alleged a culture of abuse that included imprisonment, forced labor, psychological manipulation and harassment against anyone who spoke out against the church. (The church has denied these claims.) Despite the negative publicity, Tom Cruise, Elisabeth Moss and John Travolta are still high-profile members, and the church owns many Hollywood-area landmarks.

Bixler-Zavala was welcomed into the inner sanctum of the Celebrity Centre, where he joined Scientologist actors like Giovanni Ribisi, Jason Lee and Michael Peña. (Lee has since left the church.) “They built me up and scratched my back,” says Bixler-Zavala. “I remember one time they gave me like $10,000 worth of books, and I’d show up to gala events and be seated around other celebrities,” he said. “When I look back at the way I was, I think I was an annoying prick.”

Bixler-Zavala’s religion had become a wedge behind the scenes when the Mars Volta broke up in 2013. His immersion in its culture alarmed friends. Bixler-Zavala and Rodríguez-López endured a stormy, off-and-on friendship (sometimes not speaking to each other, sometimes playing in shared side projects) for years after.

“Friends and family were supportive at first, if that was going to be that thing that worked for me. But some were vocally opposed,” Bixler-Zavala said. “I was stuck in my issues and my own bubble world. I couldn’t see past any of that.”

Runaways songwriter Kari Krome is suing the estate of Kim Fowley for sexual assault. She also accuses DJ and nightclub owner Rodney Bingenheimer of sexually assaulting her when she was 13.

In 2019, several years after first learning about other alleged victims, Carnell Bixler sued the church. “I could see the crisis of faith in her when they made her feel like this was her fault,” Bixler-Zavala said, echoing claims in the family’s civil suit. “In Scientology, certain emotions are just bad; it’s bad to go the route of any medicine, self-help, psychiatry. It’s bad to question anything. It was like we lived in North Korea.”

Then began the grueling, humbling work for his band and friends to trust in him again.

“Anger can really blind you and keep you from any accountability,” Bixler-Zavala said, turning toward his bandmate. “One of my saving graces is having him in my life. Him being so patient with me, it’s a humbling experience. I haven’t always been that way with him, and yet he’s allowed me to make amends and own up to my past.”

“I think you have to love the decisions you’ve made, even when you’ve been wrong,” Rodríguez-López replied.

The band’s self-titled comeback album last year was their way to lend shape to the confusion of the last decade. It sported their most streamlined arrangements and their boldest declarations of unbridled rage.

The humid menace of “Que Dios” might be an even better fit for these songs. Latin folk always hovered in the background of the band’s records, but now Rodríguez-López lets it bloom — classical guitars, skittering percussion and a confident hand with Caribbean, Mexican and South American rhythms.

“From the beginning, that was a designing principle of the band, honoring our roots and honoring our dead,” Rodríguez-López said.

The band ends the video for the single “Graveyard Love” with a Spanish quote from Lolita Lebrón, the Puerto Rican activist who attacked the U.S. Capitol in 1954: “I did not come to kill anyone, I came to die for Puerto Rico!”

“Colonialism is always at the forefront of my mind,” Rodríguez-López said. “It’s such a complex history, one that most people are ignorant to. Puerto Ricans have no power over the laws that govern us, we’ve suffered a land grab and forced sterilizations. The United States has this hubris where we want to go to Mars, but the same people who could fix the electrical grid in my country in a matter of months won’t do it.

“The one thing that keeps us together,” he continued, “is our resilience, and still trying to live a fruitful life.”

Eslabon Armado and Peso Pluma’s ‘Ella Baila Sola’ is the first Mexican regional song to reach the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

Bixler-Zavala is trying to do the same today. He likes Texas outlaw country and the ways it meshes with his Mexican heritage. In this new setting, his lyrics about Scientology, like on “Graveyard Love,” ring like a dusty revenge ballad.

“In that house, you know I lost myself every time,” he sings on “Blank Condolences.” “My nails scrawl in blood, I will always haunt you / Burn your fields of sage, it won’t keep me from collecting that bounty on your head.”

“That’s directed at certain people that have caused my family harm,” Bixler-Zavala said point-blank. “I’m lifting up the carpet and showing where certain roaches are.”

In November, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Charlaine Olmedo declared a mistrial at Masterson’s rape trial after jurors deadlocked. In her testimony, Carnell Bixler alleged that her romantic relationship with Masterson turned violent in the early 2000s, including multiple rapes and physical assaults. (Carnell Bixler declined to speak to The Times.)

In the civil suit, she alleges that “Masterson regularly forced Plaintiff Bixler to have sex with him and became violent when Plaintiff Bixler refused. In one instance, after Plaintiff Bixler refused sex, Masterson dragged Plaintiff Bixler naked across their bedroom floor while berating her appearance. He then threw her, still naked, into the hall and locked the bedroom door.”

She said she reported Masterson to the Church of Scientology’s ethics officer, yet, according to her suit, was told “she was not raped, because you can’t be raped by someone you are in a consensual relationship with.’” She claims the ethics officer asked “what she did to cause the assault and ordered her to complete an ethics course.”

“It, like, almost put me in a state of terror and I understood I needed to do as I was told and not tell anybody,” Carnell Bixler told the criminal trial’s jury. “They would destroy me.”

Scientology responded in a statement, “The Church has no policy prohibiting or discouraging members from reporting criminal conduct of anyone, Scientologists or not, to law enforcement. Quite the opposite. Church policy explicitly demands Scientologists abide by all laws of the land. All allegations to the contrary are totally false.”

In the civil suit, the Bixlers claim that the church’s agents have “systematically stalked, harassed, invaded their and their family’s privacy ... to silence and intimidate them.” They allege their home security system was repeatedly hacked, Carnell Bixler’s phone “ported” to reroute data, and their car and home were broken into.

In October of 2017, the suit alleges, “Plaintiff Bixler was driving on the street where her home was located when she was chased by two of Defendants’ agents in a vehicle who were filming her. Plaintiff Bixler was so frightened that she drove to the local police department.” In June of 2019, “a friend of Defendant Masterson’s contacted Plaintiff Bixler-Zavala and threatened to leak nude photos of an underage Plaintiff Bixler.”

The suit also claims that in 2017, their “family dog died inexplicably. They requested an autopsy and learned that the dog died of unexplained traumatic injuries to her trachea and esophagus.”

In 2020, the suit continues, they “discovered an amount of ground meat had been thrown over their fence into their back yard. The meat had been packed around a rectangular tablet of rat poison. The Bixler Plaintiffs soon learned that one of their dogs had consumed the raw meat and rat poison. The dog would die as a result of ingesting the poison. In the days following the death of their dog the Bixler Plaintiffs also discovered ground meat in the area of their fence to their driveway. Packed within the ground meat was broken glass.”

A Scientology spokeswoman stated that “Cedric Bixler-Zavala and his wife’s claim that the Church ‘murdered’ their dogs is a flat-out lie.” The spokeswoman added that Carnell Bixler blamed a dog kennel on social media for one dog’s injuries, and states that the Church did not hear directly from LAPD about any alleged dog-poisoning incident.

Mike Rinder, the former chief executive of Scientology’s Office of Special Affairs (the church’s international legal and communications division) left the church in 2007 and joined the board of the Aftermath Foundation, a support organization for ex-Scientologists. He hosts the podcast “Scientology: Fair Game” with actor and fellow former Scientologist Leah Remini, and wrote a memoir “A Billion Years: My Escape From a Life in the Highest Ranks of Scientology.”

He said it would not be surprising if the church tried to silence high-profile former members like the Bixlers.

“If they get Scientology pissed off at them, they will lose friends and family to disconnection. Those who are Scientologists in good standing will be ordered to cease all communication with them, and they know that Scientology engages in ‘Fair Game’ to smear and harass those they don’t like,” Rinder told The Times in an email. (“Fair Game” is an alleged Scientology belief that those who run afoul of the church can justly be harassed and threatened.)

Bixler-Zavala says that he and his wife still live in constant fear. “My life is at the point where if my phone rings in my house, my children go and hide under their bed,” he said, referring to his 10-year-old twin sons. “My kids know a monster did something bad to their mom.”

Whatever the outcome of the new trial (which is expected to last up to two months) or the civil suit, the experience has made the couple, and the band, “as thick as thieves,” Bixler-Zavala said. The Mars Volta will be on tour for most of 2023. “It’s us against the world.”

“Whether it’s this family of four people against a huge institution, or whether it’s my own country that’s still the oldest colony in the world,” Rodríguez-López said, “you can still be full of love, and not just bitterness and hatred. That means, in some way, we are winning.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.