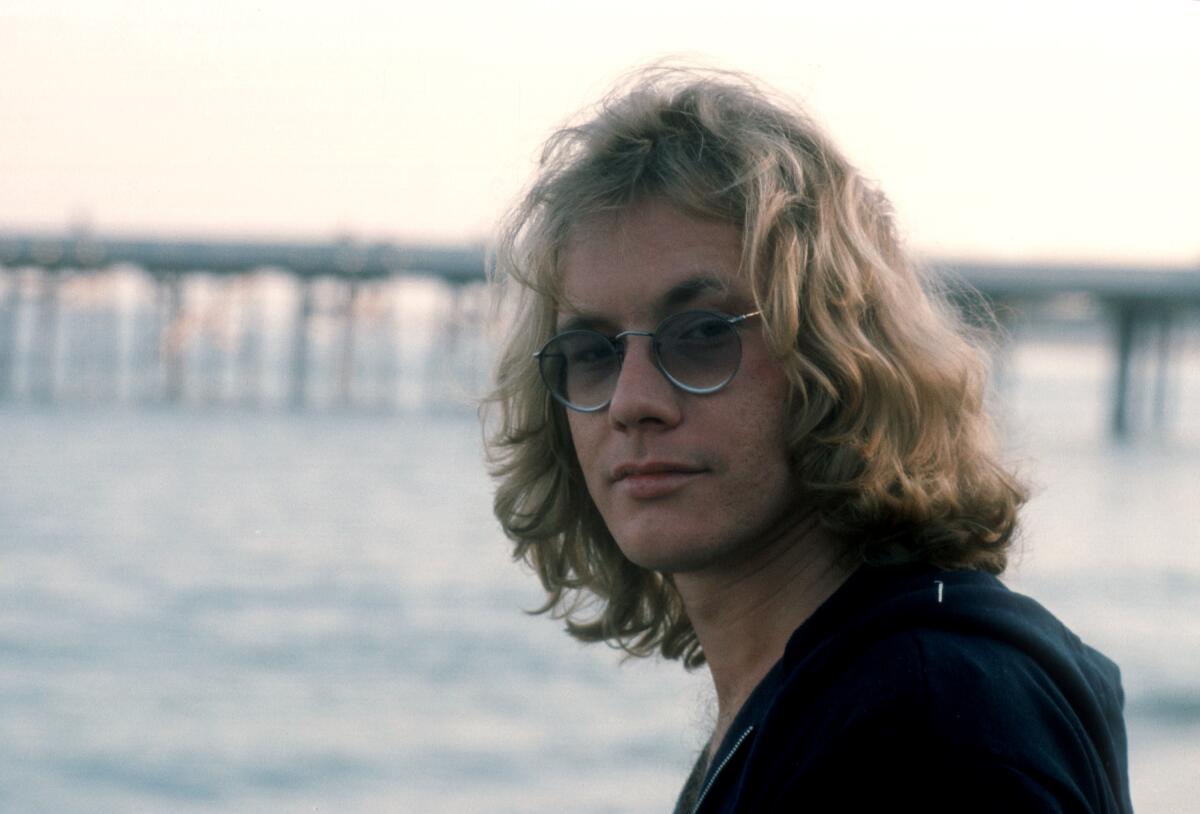

‘The soul of L.A.’: 20 years after his death, the stars are aligning for Warren Zevon

Shooter Jennings knew “Carmelita.” He knew “Lawyers, Guns and Money.” And of course he knew “Werewolves of London,” Warren Zevon’s 1978 rock hit about a “hairy-handed gent” on the prowl for “a big dish of beef chow mein.”

“It’s kind of the low-hanging fruit” of Zevon’s catalog, Jennings says of “Werewolves,” which after scraping the top 20 of Billboard’s Hot 100 went on to reach new audiences in the late 2000s when Kid Rock borrowed its strutting groove for his song “All Summer Long.”

But until three or four years ago, Jennings — the Los Angeles-based musician and Grammy-winning producer whose father is the late outlaw-country pioneer Waylon Jennings — had never dug deeply into Zevon’s work. That’s when a friend pushed him to check out “Desperados Under the Eaves,” the gut punch of a closer from Zevon’s self-titled 1976 LP in which the booze-soaked narrator contemplates his sorry situation from an air-conditioned room at the Hollywood Hawaiian Hotel.

“So I listened to it,” Jennings says. “Then I listened to it 3,000 more times.”

What he heard in Zevon’s heart-rending yet bleakly hilarious lyrics — “And if California slides into the ocean/ Like the mystics and statistics say it will/ I predict this motel will be standing until I pay my bill” — was “the most blatantly honest songwriting I’d ever encountered,” Jennings says. “He’s owning up to a failure of emotional adulthood in that song, like he’s f— his life up and he’s putting it on parade.”

“Mind-blown,” as he puts it, by the discovery, Jennings, 43, spent the next couple of years absorbing everything Zevon recorded over an idiosyncratic career that made him a cult-fave avatar of L.A.’s dark side and a musician’s musician beloved by ’70s superstars like the Eagles, Fleetwood Mac and Linda Ronstadt. Now Jennings is set to show off his studies Friday night in a concert tribute to Zevon at the Roxy in West Hollywood with a band he’s calling the Werewolves of Los Angeles.

“Hunter S. Thompson used to say that he’d retype Hemingway novels as a way of getting inside the art,” Jennings says, referring to the influential gonzo journalist who was a close friend and collaborator of Zevon’s. “That’s what it was like to learn these songs.”

Twenty years after Zevon’s death from cancer at age 56, the Roxy gig is just one manifestation of a surge of interest in his wise and witty songs about love, sex, addiction, murder, history and geopolitics. Andrew Slater, the veteran record producer and music manager who produced several of Zevon’s late-’80s LPs, is at work on a film project about Zevon with the cooperation of the late singer’s family. Last month, the War on Drugs covered Zevon’s “Play It All Night Long” at a show in Philadelphia with help from Craig Finn of the Hold Steady. And then there’s the chapter in Bob Dylan’s new book, “The Philosophy of Modern Song,” dedicated to Zevon’s 2003 tune “Dirty Life and Times,” about which the rock legend writes that “the artistry jumps out at you like spring-loaded snakes from a gag jar of peanut brittle.”

All this comes amid Zevon’s surprise nomination, announced Wednesday, to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Among his high-profile supporters was Billy Joel, who wrote a letter to the hall’s nominating committee urging them to consider Zevon, who became eligible for induction in 1994 but had never made the ballot. (Rock Hall rules say an artist or band becomes eligible 25 years after the release of their first commercial recording.)

Other first-time honorees Sheryl Crow, the White Stripes, George Michael and Cyndi Lauper join return nominees Kate Bush, Soundgarden and A Tribe Called Quest.

“I just wanted to put in my two cents of supporting Warren Zevon to be included,” Joel tells The Times. “If anyone deserved to be, he did. He was a real original, and I don’t know if that’s appreciated enough.” Joel, who was inducted into the hall in 1999 and who says he’s written similar letters on behalf of Joe Cocker and 2023 nominee Cyndi Lauper, remembers seeing Zevon perform in the late ’70s at a club near Philadelphia. “The first minute I saw him, I was knocked out. He was like the crazy brother I never had. He was fearless, and it stuck with me. I never thought he got the attention he deserved.”

Asked why, Joel says, “Well, he was a piano player, and we all tend to get lumped into this thing of ‘They’re not real rock guys’ — which I don’t think is fair, but I understand why it happens. Piano is perceived to be this middle-of-the-road instrument only played by dorks. But when I saw Warren, he was kind of breaking the piano to pieces, little by little, which I thought was an interesting style.”

Breaking the piano literally or metaphorically? “Metaphorically, but physically too,” says Joel, who adds that he and Zevon “downed a lot of vodka” after the show while commiserating over “what a pain in the ass it was to schlep around these clubs and have to deal with whatever piece of junk they had available to play.”

“Piano is actually a percussion instrument,” Joel says. “Most people think it’s a stringed instrument, but you play it like a drum. And Warren, he really fulfilled that role. He banged it, and he banged it good. Even without amplifiers, he was getting the most volume he could get out of that thing.”

Zevon paired that “primal” musical approach, as Joel puts it, with a literary sophistication in his lyric-writing that Jennings compares to the low-life poetry of Charles Bukowski and Slater says evokes the hard-boiled detective fiction of Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald.

“There’s so much to uncover once you peel it back a bit,” says the War on Drugs’ Adam Granduciel. “All the songs I love from him are because of two or three lines where you’re just like, ‘Man, you could spend your whole life trying to write something that pure.’” As an example, Granduciel cites Zevon’s “Accidentally Like a Martyr,” which the War on Drugs has played in concert. “‘Never thought I’d have to pay so dearly for what was already mine,’” he says, quoting Zevon. “Really sums it all up, you know what I mean?”

“Just the titles of his songs alone were great,” says Joel. “‘Accidentally Like a Martyr’ — God knows where you can go from there.”

Zevon, who was born in Chicago to a Mormon mother and a Russian Jewish father he described as a gangster, grew up in L.A., where as a kid he hung out a few times with Igor Stravinsky and where he eventually found work writing songs for pop acts including the Turtles before making a debut album of his own in 1969 that quickly went nowhere. By the mid-’70s, having put in a few years as the Everly Brothers’ musical director, he was ensconced in the L.A. soft-rock scene dominated by Fleetwood Mac — Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham were his roommates for a spell — and Jackson Browne, who produced “Warren Zevon”; the LP featured cameos by Nicks, Buckingham, Bonnie Raitt, the Eagles’ Glenn Frey and Don Henley and the Beach Boys’ Carl Wilson, who provided the elaborate vocal harmonies in “Desperados Under the Eaves.” Ronstadt went on to cover four of the album’s tunes, including “Carmelita” and “Poor Poor Pitiful Me,” which she made into a Top 40 radio hit.

“I really admired Warren’s writing,” Ronstadt tells The Times. “He had a literate, quirky sensibility. He was the only songwriter I knew with a subscription to Jane’s Defence Weekly,” a magazine that reported on military news and technology.

“I think his self-titled album is the defining document of mid-’70s Southern California music,” says Slater, who directed the 2018 documentary “Echo in the Canyon” about the previous decade’s Laurel Canyon scene. “Warren was exploring the shadowy underbelly of L.A. and its excesses — the idea of the bohemian-cowboy guitar player-slash-gunslinger — with his razor-sharp, sardonic sense of humor.”

Zevon filled his songs with seedy L.A. references: the heroin addict in “Carmelita” going to meet his dealer “down on Alvarado Street by the Pioneer Chicken stand,” for instance, and the guy in “Poor Poor Pitiful Me” who meets a woman at the Rainbow who asks him “if I’d beat her.” And by all accounts — including that of his ex-wife, Crystal Zevon, who wrote an unsparing 2007 biography, “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead” — Warren Zevon lived the experiences he chronicled.

“You listen to his work, and you go, ‘What was this guy thinking? What was this guy drinking?’” Joel says. “Well, he was thinking L.A. He was drinking L.A. He picked up on a lot of the macabre and the weird and the spiritual essence of the place. I thought he exemplified the soul of L.A. — if there is one.”

“Warren got the attention of every established artist in L.A., and he completely won them all over,” says drummer Russ Kunkel, who played on Zevon’s 1978 “Excitable Boy” album and with Joni Mitchell, Carole King and dozens of others. “He could be gruff if you caught him on a bad day. His persona was kind of edgy. But to see that much talent in one person — there was no way anyone could deny it.”

For Jennings, what distinguishes Zevon’s music — and what perhaps has fueled his resurgence at a moment when toxic masculinity has become a subject of cultural discourse — is his willingness to implicate himself in his bad behavior and to describe its costs to those around him.

“There are so many a—holes in rock ’n’ roll, but Zevon is one of the only songwriters that doesn’t throw women’s lives away or minimize their experience,” he says of tunes like “Desperados” and “Excitable Boy,” a savage and prescient critique of male privilege. “He acknowledges his own piece-of-s—ness. The world is changing, and we’re looking back at a lot of people who were icons and realizing, ‘Wow, they were depraved.’ Zevon was like, ‘Hey, I’m depraved, but I’m honest.’ Right out of the gate, he said he was cancelable.”

Jennings, who co-produced Brandi Carlile’s last two studio LPs — including “In These Silent Days,” which is nominated for album of the year at Sunday’s Grammy Awards — debuted his Zevon tribute at October’s Rebels & Renegades music festival in Monterey. He’d burned out on performing his own country-rock material but had been inspired by Carlile’s 2019 performance of Joni Mitchell’s “Blue” at Walt Disney Concert Hall and by a set of Elvis Presley covers Glenn Danzig played in 2021 at the Hollywood Roosevelt.

“The festival pay was pretty good, so my wife was like, ‘Why don’t you do the same thing with that dude you’re obsessed with?’” Jennings recalls with a laugh. The show dovetailed with his and Carlile’s work producing an upcoming album by Tanya Tucker — the follow-up to her Grammy-winning 2019 comeback, “While I’m Livin’” — modeled on the crisp but lived-in sound of Zevon’s self-titled LP; bringing the show to the Roxy, where Zevon cut the 1980 live album “Stand in the Fire,” adds another layer of history to Jennings’ campaign to celebrate an artist who kept pushing himself until the end.

In the summer of 2002, Zevon was diagnosed with mesothelioma and told he had just months to live; he immediately got to work on what would be his final album, “The Wind,” and even invited a VH1 film crew to document the recording process, which involved contributions from famous friends including Henley, Browne, Tom Petty and Bruce Springsteen. Zevon ended up living long enough to see the album come out and to make a much-discussed appearance on David Letterman’s late-night show in which he joked about his condition and said his advice to those he was leaving behind was to “enjoy every sandwich.”

“I’m sure he had trepidations about what was going to happen, but he just went ahead and kept banging away,” says Joel. “He was a brave man. I admired that.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.