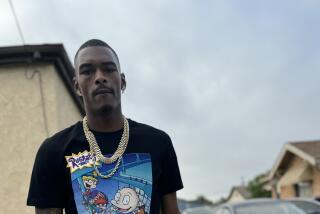

Pusha T on Kanye West, perfecting coke rap and the Grammys and hip-hop

The most vicious, masterful street-rap album of the year was written by a 45-year-old Virginia dad who can’t wait to get home to his family after work.

Pusha T’s “It’s Almost Dry” is a 12-song switchblade of a record from one of rap’s most focused craftsmen. Pusha T, born Terrence Thornton, came up as one half of the beloved brother duo Clipse, from the same freewheeling Virginia scene that birthed Missy Elliott and Timbaland. Alongside super-producer Pharrell, who always kept room for the rapper’s trademark snarl in his schedule, Pusha perfected his drug-trade storytelling over skeletal, disorienting beats.

“It’s Almost Dry,” nominated for best rap album at the upcoming Grammy Awards, is a late-career highlight, with production split between Pharrell and his other longtime creative partner, Kanye West. The two have collaborated on records since 2010, and Pusha T took the reins of West’s Def Jam imprint, G.O.O.D. Music, from 2015 through this year.

In a conversation with The Times, Pusha did not hold back about West’s unraveling, the spate of rappers dying far too young and his decades in rap doing one thing perfectly.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

“It’s Almost Dry” is your first album to debut at No. 1 on the Billboard 200, and you did it at age 45. How are you still refining your craft and getting better at this 20 years into your career?

That’s what I’m in music for right now, to show that hip-hop does not age out. When you think about early hip-hop and the greats before me, you realize that they had such a short window. No one ever really lasted this long, and to actually be competing, it’s kind of unheard of.

One thing I’ve always admired about your work is how you sequence albums. Every LP has a clear concept and is really precise — no skips. When does an album become complete for you?

I rarely do extra songs. I know exactly what it is that I’m looking for when I go into making an album. With “It’s Almost Dry,” it was to make the purest, most uncompromised hip-hop album I could. That meant the lyricism had to be A-1, and I felt it would be eventful to pit Pharrell Williams versus Ye. These two producers are hip-hop at its purest core. The passion between the three of us alone is enough to know that you’re gonna get the album of the year.

You’re known for some trademark themes in your music. It’s astonishing how you’re always able to find fresh takes on the drug underground. It’s like Martin Scorsese having interesting things to say about the Mafia after 50 years.

I don’t think that’s it hard to find something fresh in street culture. It’s something new every day, it’s action. For me, that’s inspiring. You can look at all types of different artists today, and there’s so many subcultures and subgenres of hip-hop, but it’s all really based in the streets. People act like it’s a hard thing to do, but for me, it’s not. Street culture is the basis of America. America was founded on illegal activity. It’s just the fact that coming from the inner city and being Black, it never gets looked at in a rags-to-riches type of storyline. Some of the families that have made fortunes off of illegal business, today they’re looked at as iconic.

Look at the Sacklers, who made billions selling opioids. You could easily write an album about them.

Of course. Street culture for young Black males is kinda the same thing.

After a disappointing sophomore album, Ricch returns with a fierce new mixtape and attitude: ‘When you’re waking up and it ain’t right, you gotta shake back.’

You and Pharrell Williams have spent your lives working together. What does he bring out of you, and vice versa?

Pharrell is always trying to create a whole movie. This is not just a beats-and-rhymes situation. He wants the listener to be able to dive into the emotion, and he tries to pull that emotion out of me lyrically and even in cadence. When we record, he actually treats me like an R&B singer.

The album opener, “Brambleton,” is about Clipse’s old manager, Anthony “Geezy” Gonzalez, who claimed to inspire a lot of your songs about the drug trade. It feels really raw and sad. Why did you feel ready to open up about that?

I always admired the fact that Notorious B.I.G. started “Life After Death” with his story. I finally figured that I had a strong enough story that people would be able to relate to, and you’d be able to hear and feel the emotion in what I’m saying. I had never felt like I had one of those records before. “Life After Death” is one of my favorite albums of all time, if not the best album of all time. I was always envious that I didn’t have that story, and being a rapper like myself, everything turns into a competition.

Let’s talk Grammys. This is your fifth nomination so far, but no wins yet. No rap album has won album of the year since Outkast’s “Speakerboxxx/The Love Below” in 2004. Kendrick Lamar has won a Pulitzer Prize, but not album of the year. How do you feel the Grammys have treated hip-hop in recent years?

It’s strange to me. I’m thinking of certain albums that, off the top of my head, could’ve won album of the year. Definitely [Lamar’s] “good kid, m.A.A.d city” and [West’s] “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.”

How is your relationship with your brother No Malice these days? He’s on your new record, but he’s been on his own path since Clipse split up. Are you still close?

He actually just left me here in L.A. We’re in contact every day. We talk about everything. The relationship is second to none. When he heard this album, he was like, “Oh, you’re taking this to a whole other level.” I had to explain my mentality behind why I’m going so hard. Being in it for 20 years, my goal is to show that I can compete at the highest level.

Speaking of family, you had a son a couple of years ago. How did that experience change your worldview and your values?

I’ve noticed a new focus in my music because I’m always trying to get back home to my son. I don’t waste time. I go in, I get it done, and I go home.

This is the part where we have to talk about Kanye. First, let’s talk about your collaborations on the album, like “Dreamin of the Past,” “Rock n Roll” and “Diet Coke.” What’s writing and recording with him like? How do those songs show the dynamic that you two have together?

Writing and recording with Ye is a very special thing for me. We actually have a lot of the same taste, we love just barred-out rap. He would tell me things like, “Man, you just be the extreme version of yourself. And I’m gonna be the extreme version of myself.”

Before all the recent events, what has he meant to you as an artist and a friend over the years?

Creatively, Ye has meant freedom to me. A lot of times, people would try to get me to change certain things about my process, change certain things about me lyrically, change certain things about the content. He never has been like that. He always saw me for who I was and knew how to take it to the next level.

As someone who has known him for a long time, how have you felt watching everything that’s happened with him over the last few months?

It’s definitely affected me. It’s been disappointing. As a Black man in America, there is no room for bigotry or hate speech. So yeah. It’s been very disappointing, let’s talk straight.

When Ye released ‘Donda 2,’ you could only hear it through a device called the Stem Player. Its creator, Alex Klein, speaks out on the end of their partnership.

This has been a rough few years for young men in hip-hop. Nipsey Hussle, Pop Smoke, Young Dolph, PnB Rock and Takeoff were all killed, among others. Has that changed how you move in the world?

I definitely move with caution. Like I said, I’m always trying to get home to my son. Some of the risks that I used to take, just being out and about for no reason at all, I don’t really do that too much. It has been very sad to read about all this young talent that’s passed away. You don’t even have to know people to feel that. I can’t say that I had numerous conversations with Takeoff, but I still feel for him and his family.

There are a thousand different solutions from the top with the government, but I think I’d just rather speak to the artists, face to face. Move with caution and think about your surroundings and the people you surround yourself with. We’re in the rap game. This music started in the streets. It’s a very competitive space, and sometimes that bleeds into the streets as well.

How do you see your writing about street culture evolving as you enter the back half of your 40s?

I’ve spoken about being the Martin Scorsese of street raps. I want the music to be as colorful and creative as it can be. Expand where reality meets imagination. I’m here to entertain those who love this, and there’s a lot of people who love this.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.