Arctic Monkeys’ Alex Turner on fame, Frank Sinatra and the elusive search for the ‘mega-riff’

Arctic Monkeys blasted out of the U.K. in 2006 with “Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not,” a scrappy modern-classic debut that framed the young quartet as a kind of transatlantic counterpart to the new wave of American garage-revival acts.

Seven years and a part-time move to Los Angeles later, the band conquered U.S. rock radio with the stomping and sexy “AM,” which spun off hits like “R U Mine?” and “Do I Wanna Know?” (Current Spotify play count for the latter: 1.4 billion.) Now the Monkeys — singer Alex Turner, guitarist Jamie Cook, bassist Nick O’Malley and drummer Matt Helders — are two albums deep into their older-and-weirder phase: On “The Car,” which came out Friday and follows 2018’s “Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino,” Turner croons enigmatically about disco balls and snooker clubs over slo-mo psychedelic funk that suggests an otherworldly wedding band.

Which was actually a gig Turner, 36, took up recently when he serenaded a couple of just-married friends with Dion’s “Only You Know” at their nuptials in L.A. “How’d you hear about that?” he asked a few days later over tea in a deserted Los Feliz bar. Told a guest had posted a clip of his performance on Instagram, he laughed and said, “Suppose it would be astonishing these days if that didn’t happen.”

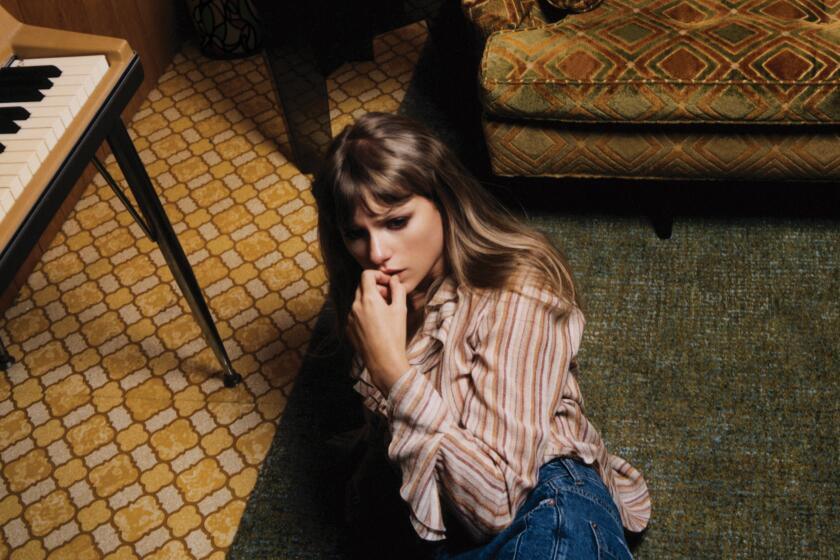

Indeed, though the Monkeys can fill arenas and headline festivals in the U.S., Turner is a proper tabloid-level celebrity (and low-key style icon) in London, where he’s back to living most of the time with his girlfriend, French singer Louise Verneuil. Dressed in a filmy floral-print shirt and smartly tailored trousers, he discussed Frank Sinatra, great hair and the death of England’s queen.

After two rootsy pandemic albums, ‘Midnights’ picks up right where 2014’s ‘1989’ and 2017’s ‘Reputation’ left off.

When you were 17 or 18, could you have envisioned yourself singing the way you’re singing now?

No. At first I didn’t even accept that I was a singer. I can’t remember really thinking about the idea of melody within the vocal performances. It was focused a lot more on just getting the words out. I can’t put a percentage on it, but I feel like there were a lot more words per 30 seconds of music in that original stage.

Does the early stuff seem overly wordy to you now?

I wouldn’t put it like that. But some of the choices I find amusing.

I caught your set at Primavera Sound a couple of weeks ago and there was this funny moment after “Why’d You Only Call Me When You’re High?” where you said to the audience, “Simple stuff — let’s hear it for simple stuff.”

Well, I’d just repeated that phrase four times in the song, and by the fourth time I said it, people were still saying it back to me. So it seemed like I needed to give some recognition to simple stuff. Not that I necessarily think what we’re doing now is extremely complicated in comparison. But a song like that — that’s on “AM,” and I reckon we had a feeling before that record of trying to go more direct in that moment. I think that tune was probably the most direct you could go.

Do you find the idea of someone asking you to explain your songs excruciating?

I don’t know if I’d go all the way to excruciating. I’m just not sure what I would say if someone were to ask me.

As a listener, are you drawn to music that can be kind of confusing?

Absolutely not. I’m drawn to straightforward things. For some reason I’m thinking about this “Sinatra at the Sands” record that I love. There’s this song, “Don’t Worry ’Bout Me” — that’s one where you can guess what it’s about from the title. But there’s stuff going on in the band and in the music that’s intricate. He does this bit that always gets me — a sound comes out of his mouth, but it’s not any of the notes. He just kind of swoops up: [Sings] “Look out for yourself.”

How’d you get into Sinatra?

Through my dad when I was a little kid. He was playing in a big band, and his stepdad was part of a big band. Between being in my dad’s car and being with my grandparents, that music was around a lot.

Does it feel reasonable to compare “The Car” to something like Sinatra?

I’d certainly be careful with that. But the fact that that kind of music has been there is probably partly responsible for why I’ve arrived at a place where I thought it was all right to scratch whatever we’ve been scratching on these last couple of records.

A thing I love about Sinatra is that he still had swagger even as he got older, lost his hair and gained some weight.

I remember when I was a kid my grandmother trying to convince me that, you know, “This is what a pop star used to be.” I was like, “What? No, that’s in a different world.” This was when the thing was, like, boy bands or whatever it was. But she was like, “This is what young people used to be mad for.”

The duo has come from nowhere — or, more precisely, the Isle of Wight — to delight U.S. rock fans with its offhand combo of pinpoint hooks and deadpan wit.

You have famously great hair. As a pop star, do you worry about losing it?

On some level, no one’s thrilled about that. But I suppose the guy with the microphone has more of a cause for concern. It’s one show at a time, isn’t it?

Say more about being the guy with the microphone. Your performance style these days feels to me like a kind of riff on that idea. There’s a self-awareness to the way you carry yourself.

Because we’re back onstage again [after the pandemic], I’m trying not to let myself do things that I would have done three years ago. I’m trying to wrangle the gestures into what’s right for this music, and I think I’m kind of starting to figure it out. It’s not as if I’m sitting down with video after a show and making notes, though in a weird way, I don’t mind that idea.

There are some historical through lines to the role, right? Harry Styles’ act runs back through you and through guys from the ’70s and back to Sinatra. When you see Harry, are you like, “Yeah, I know what that guy’s doing”?

What is the answer to that? [Laughs] I feel like I’d have to go see his show to be able to properly answer. Sooner or later I’ll get the chance.

Some Arctic Monkeys fans will hear this album and wish it was more of a loud rock thing.

I’m sure. But the rock-guitar side of things, it’s still in there — more than I expected it to be, if I’m honest. I’d been working on this for a while by myself before we had a session with the band. And in that session I started to find myself wanting to stand up and turn up the guitar amp.

Your drummer, Matt, recently told an interviewer that the “heavy riffs” were never coming back.

I can’t rule out the possibility that we’re gonna write another mega-riff. But I didn’t find one this time.

Do you enjoy being a pop star?

I have very little basis for comparison. The band has been going on for a larger fraction of my lifetime than it hasn’t, which is a threshold that’s only just been crossed. That’s the point at which you cease to be able to give a valid answer to that question.

You ever long for a more traditional life?

I mean, just like writing a mega-riff, I don’t want to rule it out. I’m not taking anything off the table.

Last thing. I saw Duran Duran play the Hollywood Bowl in September, and they put a photo of the late Queen Elizabeth on the big video screens and asked the crowd for a moment of silence.

What did the crowd do?

Kept respectfully quiet. I don’t know if you’ll have an answer to this, but if you’d been playing a show that weekend, would you have felt some impulse to comment onstage?

[Pauses] I think you were right when you said I might not have an answer to that.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.