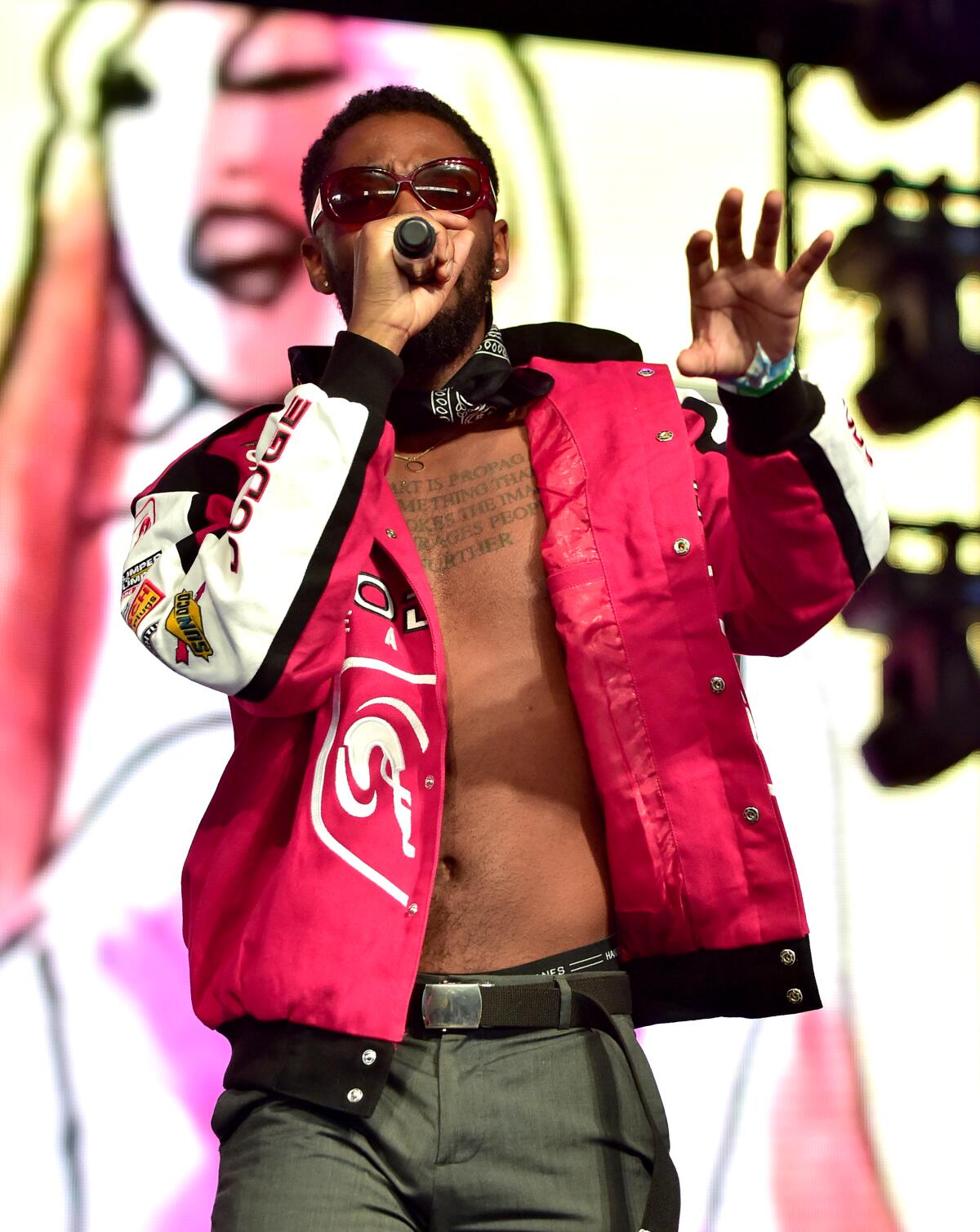

Meet Brent Faiyaz, R&B’s antihero: ‘It’s not human to be constantly writing love songs’

This summer, billboards in major cities across the country displayed the following cryptic phrase: “I would like to apologize in advance for the person I’m gonna become once this album drops.”

The billboards belonged to 26-year-old singer-songwriter Brent Faiyaz; the album in question was “Wasteland,” a cautionary, R&B-trap opera deriding fame in a time of social and political upheaval. Today, “Wasteland” debuted on the Billboard 200 at No. 2, just behind global megastar Bad Bunny.

This counts as as a massive triumph for Faiyaz who has steadfastly committed to working independently of major labels, including distribution.

“I figure I’m pretty good at doing all that on my own,” he says over the phone from a hotel in Beverly Hills.

Faiyaz was born Christopher Brent Wood in Columbia, Md., a suburb of Baltimore, to parents of African American and Dominican descent. Despite being extremely introverted as a child, he recorded freestyle raps at home in secret; it was on his Soundcloud page that he test drove the moniker “Faiyaz,” an Arabic word for “artistic,” as suggested by a Muslim classmate. Although his teen dream was to be a famous rapper, Faiyaz began slowing his flow to reveal a more silver-tongued, R&B Casanova lurking within.

“Wasteland,” a sequel to his 2020 EP “F— the World,” counts collaborations with A-listers like Tyler, the Creator (“Gravity”), Alicia Keys (“Ghetto Gatsby”) and Drake with the Neptunes (“Wasting Time”). It pushes forth R&B for a generation of chronic social media oversharers and blood-letters, keen to show their battle scars after a global pandemic left millions dead and millions more feeling lonely and adrift. Faiyaz, who once sought out the limelight, found himself hard to recognize under its glare.

“Maybe I don’t need a hug / Maybe I’m just f— up,” Faiyaz concludes on “Wasteland”’s “Addictions.”

The Grammy-nominated singer spoke to The Times about the road to “Wasteland,” the residual guilt that comes with achieving your goals, and how, sometimes, fighting your demons requires taking a swing at yourself.

You put up billboards around the country that read: “I would like to apologize in advance for the person I’m gonna become once this album drops.” Where did this idea come from?

It was the fans. They kept tweeting this line, we just took that and ran with it. From my fans’ perspective, it was fuel for them to be some type of way. For me, it’s a lifestyle thing — my life will never be the same again.

Who were you before you became Brent Faiyaz?

I was a pretty quiet kid. I didn’t really get a kick out of having a whole lot of friends. All I was really focused on was music and drawing — buildings were my favorite to draw. I liked practicing straight lines and playing with distance and shading. I loved the way shadows looked in the sunset. That s— was fun as hell to me, but now my attention span doesn’t allow me to draw anymore. My brain needed to make space for music.

How did you make the turn to music?

I started recording when I was like 11 or 12. I downloaded some cheap software to make beats, and I would come home from school and rap my feelings out. It was cathartic. It was my little secret for a while. Once I felt like I was getting good, I started burning CDs and handing them out at my middle school. Then people started wanting to be my friend, wanting to kick it. Eventually we had a clique going, we called ourselves Civilized Human Beings for a time. Lost Kids came about when I was 15 or 16.

Ten years later, Lost Kids became the name of your joint record label with your manager, Ty Baisden. Did you intend to be a strictly independent artist?

Lost Kids didn’t become a business until I met Ty in 2014. He heard my song, “Natural Release,” on Soundcloud. I was 18 when I dropped it. I spent senior year of high school on my phone, looking up industry contacts and sending links to my music. If I read an article about one of my favorite artists, I’d email the writer. I treated it like I was applying for a job.

The level of buzz around your 2020 EP, “F— the World,” was impressive — and you released it just as the pandemic touched down on the U.S.

I was supposed to do this tour and press and videos when “F— the World” dropped, but I couldn’t go nowhere. At the same time, I garnered a huge audience from all the other people who were stuck in the house. That was the best press I could get.

What was your state of mind when you started recording “Wasteland”?

I was living in Atlanta for a couple of months, [because] I was dating somebody there. But the George Floyd murder led to riots and protests. And with [COVID-19] going on, everybody done lost somebody. People were out of work. It was a pretty f—ed up time, but I was starting to make the best money of my life. I [was] buying cars and traveling from place to place. I’d be in the studio by day and protesting at night. Then I’d go to the club. That’s when I wrote the [“Wasteland”] songs “Dead Man Walking” and “Loose Change.”

Those songs are pretty nihilistic. Could you even imagine having a future at that time?

I mean, I mostly felt guilt. I was able to do all this cool s— while people were down bad. I still think we still haven’t fully coped with COVID. There is a lot of healing we as people haven’t done in the last two years.

“Wasteland” unfolds like an R&B opera of sorts: The protagonist is a young singer who wrestles with his own fame, spars with his pregnant girlfriend and implicates whomever else he feels like bringing into the mix. Is this record meant to be autobiographical?

Well, the songwriting definitely is. But the skits? Nah.

You act out some intense scenes in the skits between songs. There’s lots of psychodrama — crying, screaming — and it culminates in this epic car crash. Do you ever feel triggered by your own records?

That s— is hard to listen to. I’m not gonna lie. I was in the studio with one of the voice actors when we did the last skit. I was standing next to her, and she was shaking and crying her eyes out, because she’s a real actor. She scared me a little bit. I had to ask, “Are you good? Are you alright?”

What made you adopt this form of storytelling?

I wanted to give it the feel of a Shakespearean tragedy. A hero fighting against the evil of his own fatal flaws.

And yet you open the record with a track called “Villain’s Theme.” There’s another one called “Egomaniac.” What’s that about?

I guess the image I created for myself in “F— the World,” unintentionally, [made] people’s perceive me as negative, or “toxic.” So I was like, “OK, I can be the villain, that’s cool. But I can take it somewhere else.” I never wanted to lean too much into being good, and I never l wanted to lean too much into being bad. To be either good or bad is not human.

True.

You know? And it’s not human to be constantly writing love songs! Shawn Stockman from Boyz II Men recently wrote some tweets about R&B losing its way. Let’s be honest, bro, Boyz II Men made so many records about the same f—ing thing. We love it, they sound good, they sold millions of records. But everybody holds on to this romanticized, ‘90s idea of R&B. The music is actually very diverse and it can be about so many different subjects.

Have you ever felt hesitant or scared to share intimate, sometimes unflattering parts of yourself with people?

I feel like I had no choice. It wouldn’t resonate if I didn’t go there. Whether you like what you feel, or don’t like what you feel, the goal is to make you feel something.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.