MEXICO CITY — After a long day jammed with interviews, a music video shoot and a surprise appearance at a Mexico City reggaetón night, the Dominican rapper Tokischa decided it was time to visit a strip club.

She bounded into the dark bar just after midnight and immediately made her way to a private room. There, she was captivated by a particular dancer, not just by her look or the way she moved — but by her story.

“I was getting a dance and she was there taking notes,” Tokischa’s stylist, Caitlyn Martínez, said of the rapper. “The girl was just telling her about her life.”

“She inspired me,” said Tokischa, 26, as she and her crew spilled back out onto the street and began searching for the next party. “I’m doing a song about her.”

Tokischa’s raps — set to trap, dembow and reggaetón beats— are wildly explicit celebrations of sexual freedom, drugs and party culture. Odes, as she says in one song, to “divine filth.”

Her open-book sexuality — she is proudly bisexual, has spoken about her years as a sex worker and recently dressed as a vagina at a major awards show — has made her a queer and feminist icon in the male-dominated world of urbano music. That coupled with her rapid-fire flow, has earned her collaborations with stars including J Balvin and Rosalía.

She has, predictably, clashed with conservatives in the Dominican Republic, who have alternatively sought to censor her music videos, jail her for posing in lingerie in front of a religious altar and ban her from performing during the height of the coronavirus pandemic because of her habit of making out with female fans.

But she has also contended with criticism from progressives who have accused her of perpetuating misogynist and even racist stereotypes.

Like the long lineage of female pop provocateurs before her, from Madonna to Lil’ Kim to Cardi B, Tokischa understands that scandal is in no way incompatible with record sales. “The more they try to ban me, the more people want me,” she says.

She also grasps the double standard at play, one in which a male Dominican rapper like El Alfa can rap incessantly about sex as crudely as Tokischa does “and nobody says anything about it.”

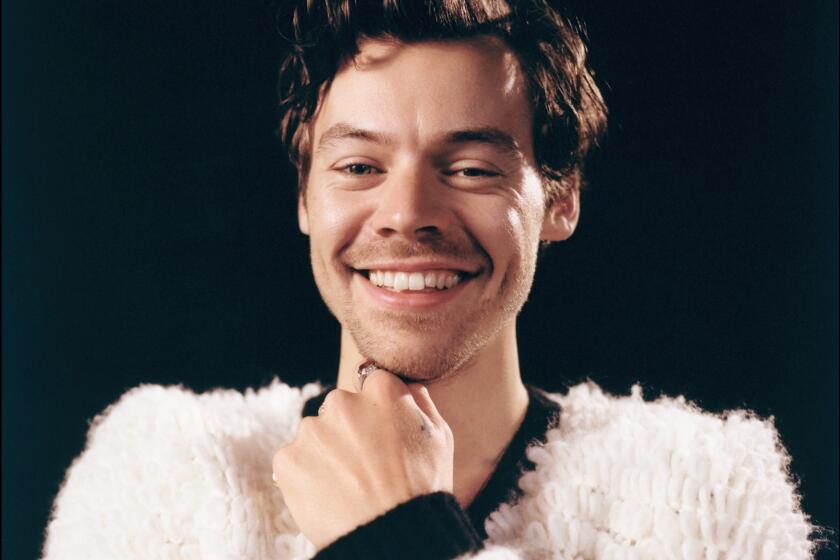

On ‘Harry’s House,’ Styles is someone to confide in and drool over, as much a woke Gen Z thought leader as a vest-with-no-shirt heartthrob.

But what Tokischa would really like people to know is that she isn’t controversial for controversy’s sake. Her work, she says, is inspired by her own experiences and those of the people around her, like the dancer at the club in Mexico City whose hard-knocks story reminded Tokischa of her own.

“They say I promote all this bad stuff,” Tokischa said. “But I express what I’ve lived through, what I’ve seen.”

Take the song “Desacato Escolar,” in which she describes students fighting, smoking weed and having sex at school. “The government got mad at me because I talk about how bad education is in my country,” she said. “They’re like, ‘You’re promoting bad habits.’ But that’s what I used to do in school. That’s what everybody does there.”

Tokischa poked fun at the idea that she’s somehow corrupting young people in the video for her latest single, “Estilazo,” an infectious voguing anthem produced by EDM producer Marshmello. In it, her music transforms a clean-cut man into a blue-haired drag queen.

“Being a bad bitch is fashionable / It’s a national trend,” she raps, her voice dripping with irony and sass. “If you upload your ass to Twitter / You’ll get thousands of likes / Money for drugs / To buy happiness.”

Tokischa was in Mexico City last week to promote the new song and to record a video for a coming track with Natanael Cano, a 21-year-old singer from northern Mexico whose traditional corridos with a trap twist have made him one of the most popular acts in Latin music.

When Cano’s producers sent Tokischa a track of bare guitar instrumentation, she shocked them by writing a sensitive verse told from the perspective of a spurned lover. “I was surprised,” Cano said. “She can write something really beautiful just as easily as she can write something really dirty.”

On set in a vacant 19th century Anglican church, Cano was in good spirits, puffing a weed vape and occasionally bursting into song. Tokischa was introspective as she channeled a woman in the throes of heartbreak. During a close-up after a scene in which she shoots Cano, fat tears rolled down her cheeks. “You’re crying,” Cano said, evidently surprised by her acting chops.

Back in her dressing room, as she changed out of a wedding dress and into a medieval gown made by a Dominican designer out of scrap fabric, Tokischa said she had been preparing her whole life to be a performer. “As a kid I used to lock myself in the bathroom and stare in the mirror and act,” she said.

The arts were an escape for what she has described as an “explicit, aggressive upbringing.”

Born Tokischa Altagracia Peralta, she spent her childhood shuffling between the homes of various relatives in Santo Domingo Este. Her father was in jail and her mother left when she was 3 to work in the U.S. as a home health nurse.

Tokischa remembers desperately missing her mother — her musky perfume, her long, manicured nails — and devouring the English-language books and fashion magazines she sent in the mail.

From a young age, Tokischa rebelled against the island’s conservative values, cutting school, talking back to teachers and sneaking listens to dembow, which peppers accelerated Jamaican dancehall riddims with slang-heavy, explicit lyrics.

She quickly ascertained that it meant something different to be engaged in such activities as a girl. Her male cousins were given free reign to roam the neighborhood, while she had to sneak out of the house. When her brother discovered her kissing a female friend, he beat her, but when he later got his young girlfriend pregnant, “nobody got mad.”

At a moment in his career when the American music industry and Hollywood are fighting for a piece of Bad Bunny, he’s fighting for his identity too.

After high school, where she sought outlets to explore her interest in theater and dance, she entered a dark period that she refers to now as the “underworld.” She worked at a FedEx call center and often showed up high on cocaine or ecstasy. Eventually, at around 19, she turned to sex work, entering “sugar daddy” relationships with a string of older, drug-addicted men. She remembers sometimes crying in the shower, trying to scrub off their smell.

Evidence of that phase covers her body. She has the letters LSD inked on her left wrist, a marijuana leaf on her butt cheek and the word “coke” on the inside of her right thigh. Her tattoos contrast with her innocent-looking face — big cheeks, wide eyes, huge smile — and earned her modeling gigs.

A 2016 session with photographer and director Raymi Paulus provided a path out of the underworld. Paulus, who had also found refuge in creativity during his own tumultuous upbringing in a poor neighborhood, had been looking for a musical artist to represent as a manager. He took Tokischa into the studio and produced videos for her that mixed her twerking with his hippie-stoner aesthetics (a recurrent theme is an alien smoking a joint). By 2018, Tokischa was moving off hard drugs and they had released their first hit.

A string of songs including last year’s “Yo No Me Voy Acostar,” in which she raps in her signature coy voice about being high on molly and enjoying the affections of “a little girlfriend who kisses me,” drew the attention of major artists like Bad Bunny, who declared himself a fan.

The international spotlight has been a lot for Tokischa, who had never left the Dominican Republic before last year and who survived the coronavirus pandemic with income from Only Fans, where she posts explicit content.

When Rosalía reached out and asked her to add a verse to “La Combi Versace,” a song about high fashion for her new album “Motomami,” Tokischa had to go shopping.

“I had never even seen Versace, so how could I write about it?” she said.

Her sudden thrust into the highest echelons of pop music hasn’t been without stumbles.

The Paulus-directed video for “Perra,” Tokischa’s 2021 collaboration with J Balvin, was taken down amid widespread anger over its representations of Afro-Carribean women, in particular a scene in which Balvin, a white Colombian, uses a leash to walk two women wearing prosthetics designed to make them look like animals. Some feminists also criticized Tokischa’s rap in the song, in which she compares herself to a dog in heat, with Colombia’s female vice president calling the lyrics “sexist, racist, macho and misogynistic.”

Earlier this year, Tokischa quickly deleted an Instagram post in which she defended Rochy RD, a rapper she has collaborated with who has been charged with paying to have sex with a minor. Tokischa had written that underage girls and boys have always been “hustling for their money.”

Writer Jenny Mota Valdez, an early supporter of Tokischa, expressed her disappointment on Twitter. “The way she continuously perpetuates sexual infantilization and ignorantly navigates serious themes ... is not okay,” she said.

Tokischa offered a sort of half-apology after the “Perra” video, telling Rolling Stone: “I’m truly sorry that people felt offended. But at the same time, art is expression.”

Speaking in Mexico City, she says blowback from the incidents doesn’t bother her and that she doesn’t really care about what anybody thinks about her, “as long as I’m cool with God.”

She knows God might not be pleased with all of her choices, like the Only Fans account, but hopes that he or she would at least understand them. “I live off my sexuality right now at this point,” she said. “I know God doesn’t like it, but he knows I need to hustle and survive.”

One thing is clear: There are many others who love exactly what Tokischa is doing.

On a misty night after a productive recording session with Alemán, a popular Mexican rapper, Tokischa, Paulus and another member of their team stopped for dinner at a brightly lit taqueria. A group of young waitresses couldn’t stop staring.

Paula Pacheco, 22, declared herself a super fan.

“I love her assertion that a woman should be able to speak openly about her sexuality and do what she wants without being judged by others,” she said. “Women are always more exposed to criticism, but if you can claim it and re-signify it with its own meaning, saying, ‘Yes, I’m a whore, yes I’m a bitch,’ it’s a kind of political protest.”

When Tokischa had finished her al pastor, Pacheco walked up with a plate piled with fried dough and banana ice cream.

Tokischa was in the middle of saying she hadn’t ordered desert when the waitress interrupted her: “It’s on me.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.