Late-COVID, late-winter Las Vegas. The Strip, near tidy as Tomorrowland, is running on muscle memory, marjoram-laced birria, the AFC/NFC championships and musical residencies — not the least of which is Lionel Richie’s at the Encore Theater at Wynn Las Vegas.

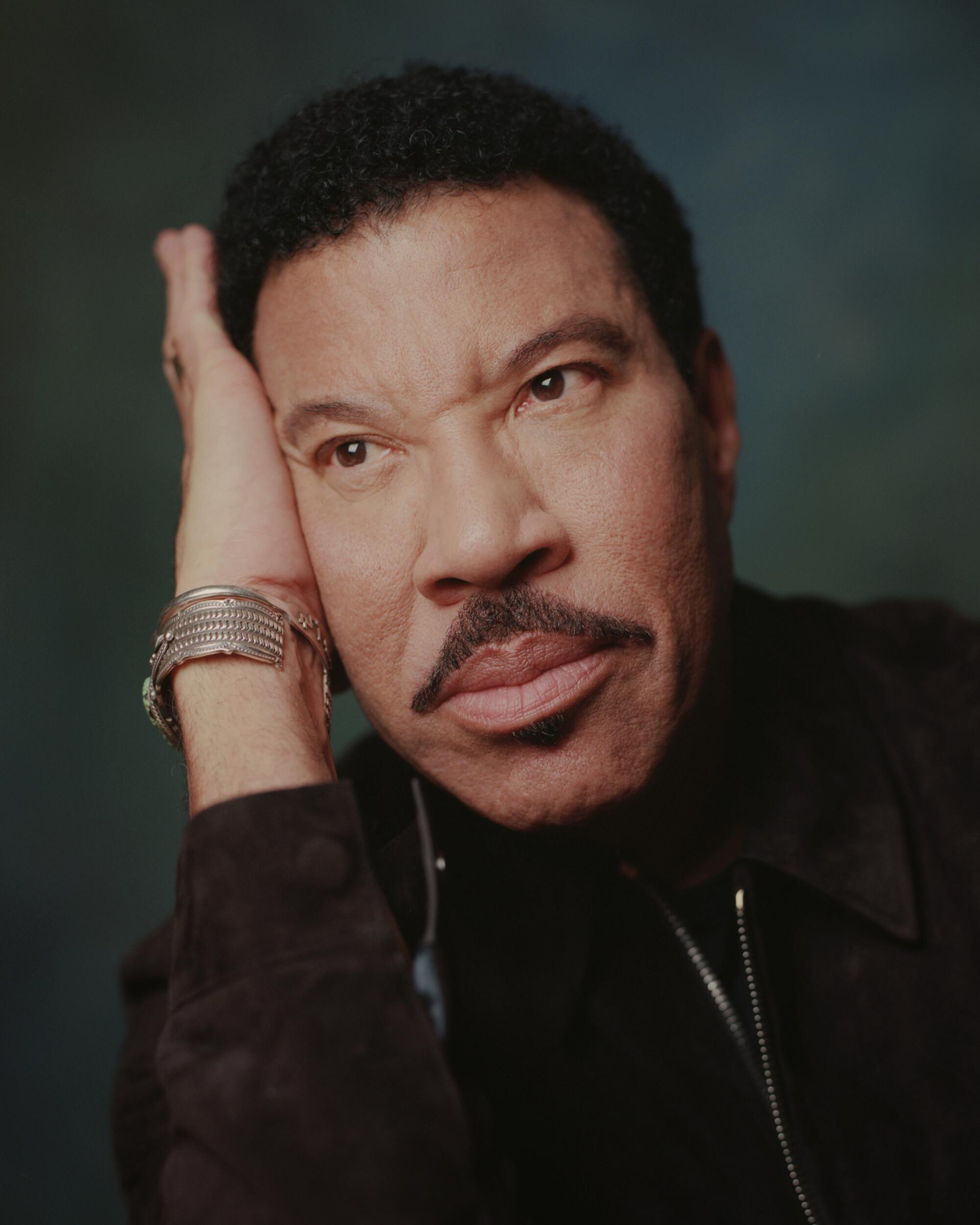

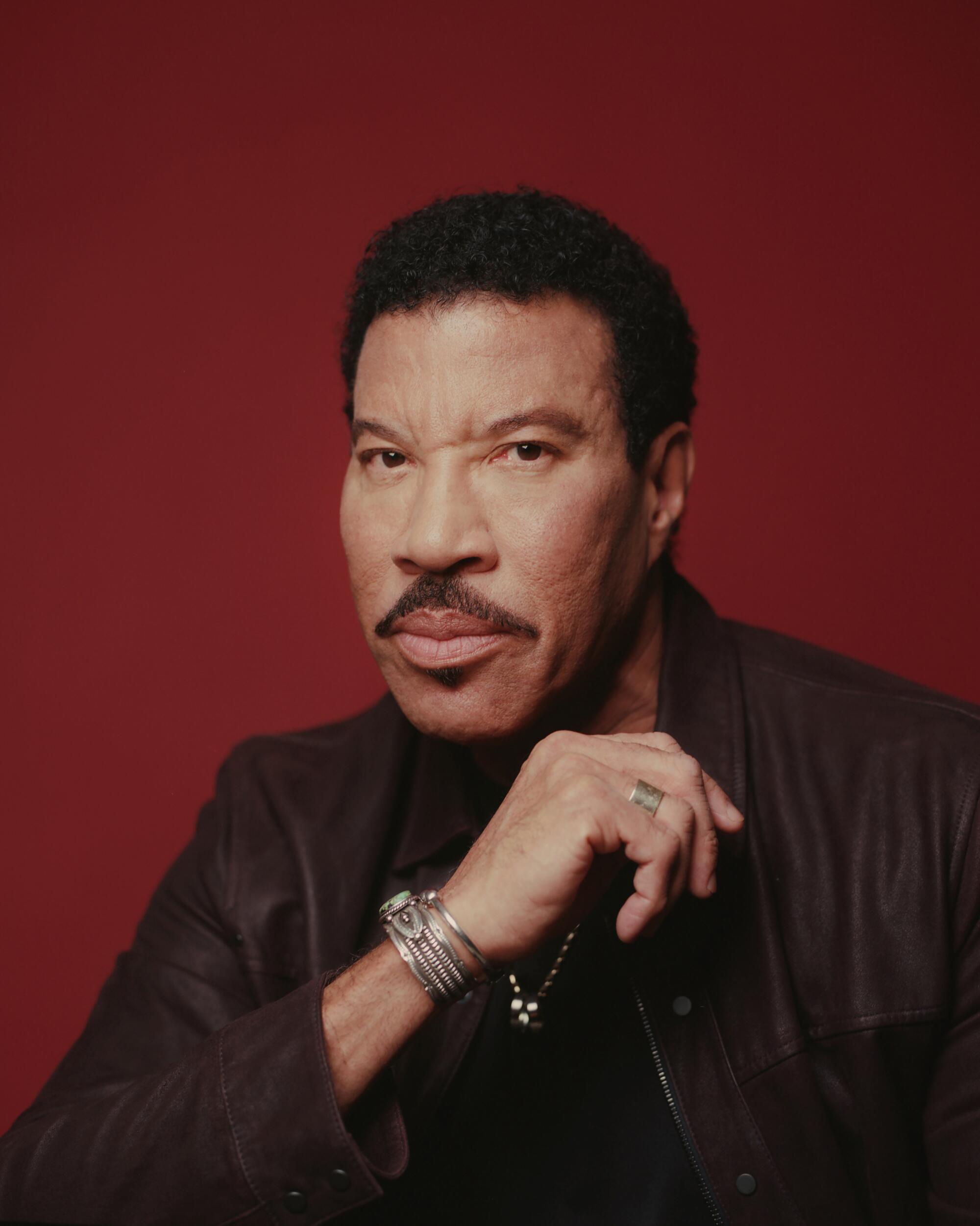

At the age of 72, Richie takes to the stage with the swag of 100 million albums sold, four Grammys and an Oscar, the Library of Congress’ Gershwin Prize for Popular Song and a minty-fresh nomination to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. The former Commodores frontman returns Feb. 27 as sensei judge of “American Idol,” now in its fifth ABC season (and 20th overall).

The Lionel Richie show is intimate — just short of 1,500 people. The audience is multiracial, skewing white. With ease, and dad jokes, Richie takes us back to when we were all — as Richie sang in 1983 — running with the night, and playing in the shadows. We know all of Richie’s lyrics, like, verbatim. Talk show host James Corden and I are in the same row, and his passion for the show is palpable. Richie’s singing voice is both raspy and clear. His ballads tremble with blues specific to the American South. We sway.

When he sings out “just thinking about you baby / just blows my mind” from his early solo hit “My Love,” a collective surge back to the Reagan era overwhelms. He’s been with us through our loves and breakups. We’ve been with him through his marriage to high school sweetheart Brenda Harvey Richie (1975-93), with whom he has a daughter, the designer and reality show pioneer Nicole Richie. After a tabloid breakup that included Harvey Richie being arrested for battery, Lionel married dancer Diane Alexander in 1995. They have two children, model-musician Miles Richie and media personality Sofia Richie. The world is fascinated by Lionel Richie’s kids (they are Kardashian- and Paris Jackson- and Good Charlotte-adjacent): His two daughters and son have a collective 13 million Instagram followers.

To a whole generation Lionel is just his famous kids’ dad, or that emotional judge on “Idol” alongside Katy Perry and Luke Bryan who advises without being judgmental. But for fans of Lionel’s own music, the sight and the sound of him on piano is enough to bring tears. He’s always been both awkward and sophisticated, and his ability — via voice, composition, mood, a spiritual reverence for his own talent — still personifies a seductive mix of vulnerability and courage.

“There was a … moment,” he said to me a few weeks earlier, “when you realize this is not a fluke. I can actually see into the next dimension. There’s a moment in time when you are just possessed … it’s only 12 notes. I just realized I knew which two or three to put together. Half of the battle is knowing what you’re looking for … it will come, but you have to have patience. I can’t tell you how many times I’ll sit there and sit there and sit there and then I’ll go buy another black shirt from a store. I don’t need another black shirt.”

That he has so often been labeled corny and schmaltzy or “not Black enough” would be laughable if it weren’t so painful to him, condescending to his fans and perfectly in line with the way the Black pop of the 1980s was concurrently uplifted by the masses and stomped on by those writing the first draft of music history. This was the era in which Richie and fellow Motown valedictorians Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross and Michael Jackson changed the personality of American pop. “I Just Called to Say I Love You” does not hold a candle to, say, “Ordinary Pain,” and “Upside Down” will never be “Touch Me in the Morning,” but the criticisms of ‘80s Black pop are so alike and steady, it begins to feel like a systemic call to stand down. They were ubiquitous and resented for that ubiquity. The music of Lionel Richie and his cohort was looked upon with disdain for having the audacity to over-perform at stadiums, on radio stations, in record stores and in the hearts of music lovers, in a way no Black artists had done — or been allowed to do — before.

And the fruits of that creativity? The Commodores’ indelible “Easy,” “Three Times a Lady,” “Sail On,” “Jesus Is Love” and “Zoom.” Richie’s “Endless Love” (with Miss Ross), “Truly,” “Hello,” “Stuck on You,” “All Night Long,” “Say You Say Me” and “Dancing on the Ceiling.” Not to mention U.S.A. For Africa’s “We Are the World,” the single that is mocked as cringe but raised the equivalent of $149 million for famine relief. Many forget that Richie wrote the song with Michael Jackson, and that it is the eighth best-selling single of all time. Lionel’s vocal leads the song. Then Stevie Wonder, Paul Simon, Kenny Rogers, James Ingram, Tina Turner, Billy Joel and on and on. In 2022, it all seems very Auld Lang Syne. We were the world, indeed.

“WE DIDN’T KNOW,” SAYS RICHIE, “that life was as rough as it was.”

In a suite at the Beverly Hills’ Peninsula hotel, a photographer rearranges furniture. Richie’s manager is scrolling, and Richie, in black from neck to toe, is fresh from “Idol” auditions. “What do I tell all the kids? Don’t get psyched out. Make sure you stay you.”

Richie was a kid in segregated post-World War II Alabama on the campus of what was then known as the Tuskegee Institute. “We called it the bubble,” he says. His parents’ home was “right at the gate of the university.” The name on the deed is educator Margaret Washington, Booker T. Washington’s third wife. “I still own it,” says Richie, “and I’ve been putting [in] money and fixing it up since I left in 1968. I probably put more money in that piece of property than any I have in the whole world.” And even if hyperbole, that’s saying something.

The property that most reflects Richie’s global lifestyle is his 17,000 square-foot, 28-room home overlooking the Los Angeles Country Club. Built in 1929 for Carrie Guggenheim, for Richie it is forever a work in progress. Filled with the arts (Basquiats, Banksys, abstracts by Miles Davis) and letters (from Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver to Richie’s grandmother) of a long, indefatigable and deeply creative American life. His home is both a haven and a palace regularly included on celebrity bus tours. “I feel about my home the way I feel about my music: you have to take chances,” Richie told Architectural Digest in 2007. “When I wrote ‘All Night Long’ [and] ‘Three Times a Lady,’ it was dangerous, because at the time black guys were singing neither calypso … nor waltzes. But since you only get one shot at life, let’s make it a challenge. That’s how I feel about this house.”

The kid who would eventually be inspired to paint his Beverly Hills mansion the palomino hue of a cardinal’s Lake Como home used to play with his pals near the planes flown by Tuskegee’s famed Airmen. Richie didn’t know the Airmen were famous until he got to high school, but their work ethic and glamorous energy had an effect on him.

“They were just nobodies to America,” he says of the segregated 332nd Fighter Group and 477th Bombardment Group of the U.S. Army Air Forces. “Imagine coming home and you … didn’t lose a plane that you were protecting. And you watch Walter Cronkite’s ‘The Twentieth Century.’ And there’s not one mention of you in that whole program. Hey we’re [flying missions over] Normandy and … then nothing.”

It could feel safe on the Tuskegee campus — insulated in some ways from Alabama’s culture of lynching. Legal and customary American apartheid was not so long ago, and Lionel Brockman Richie Jr. was raised in it. “We had no idea that the Klan was marching through town,” he says, “because they put us to bed early.”

But he was not shielded altogether. No one was. “I went to Montgomery with my father,” says Richie. “I’m … 6 years old. I went over to the water fountain … didn’t see the sign above it, and just drank the water.” The razor-wire tangle of ordinances known as “Jim Crow” laws were in full effect. At the Peninsula hotel suite Richie’s bright eyes are focused on a moment from nearly seven decades ago.

“These guys were saying something to my dad. I kept thinking, ‘These guys better be cool because my dad’s gonna kick their ass.’ My dad kept walking and got in the car. No! Why didn’t my dad turn around and just smack them?” Years later, when Richie confronted his father, the response was pragmatic. “I had a choice that day of either being a man, or your father,” said Lionel Richie Sr., a U.S. Army analyst. “If I turned around acting like a man, they’d have probably shot and killed me.” As for the son? The one whose music would one day be adored by Nelson Mandela? “It was at that point,” says Richie, “I realized there was something happening outside of the bubble.”

Whether he was in Alabama, or in Illinois for high school, Richie was a nerdy kid. His mother was an educator. His maternal grandmother, Adelaide Brown, was a pianist and music teacher, and one of Richie’s uncles, a sometime arranger for Duke Ellington, gave young Lionel his first saxophone. Next came practice. Then ambition, plus a decision to not become an Episcopal priest. Finally, Richie formed a trio called the Mystics (they performed at proms), which transmogrified into the Commodores.

He wasn’t quite a natural. Richie recalls once walking off the stage of a Tuskegee talent show — with the curtains. “Just having an audience looking at me,” he says, “was terrifying.” It’s why he has empathy for and keeps it real with “Idol” contestants. “When these kids walk out, some of them have this confidence of ‘I got this.’ And … no, you don’t. ‘Cause in your head, who told you you had this? Well, your mama told you that, your uncle told you that. [The kids say,] ‘Well I sing in church with my mother and father.’ Let me tell you something, how to navigate a song is not how loud you sing. How you navigate a song is the story you tell.”

On a summer break, the Commodores hoofed it to New York City, ended up with an agent, and by the next summer, they were opening for the Jackson 5 on the group’s 40-city 1971 tour. At the time, the Motown singles machine was morphing into album mode with the success of the Jackson 5’s “ABC” in 1970 and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” in ‘71, and the United States spun into a Jackson mania that included television specials, a book and a cartoon series. So the Commodores were swept into the massive ambitions of Motown — the sound, as team Berry Gordy manifested, of young America. The tour cemented Lionel Richie’s friendship with Michael Jackson. It was the start of something big.

The next decade, Jackson and then Lionel Richie won the prestigious album of the year Grammys for “Thriller” and “Can’t Slow Down,” respectively (1984 and 1985). Back-to-back big Black pop. I remember the night Richie won that Grammy — the odds against him had to have been super long. Richie beat Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.,” Tina Turner’s “Private Dancer,” Cyndi Lauper’s “She’s So Unusual” and Prince’s “Purple Rain.” That Grammy is one of just four he has, on 32 nominations. I tell Richie that as he gave his ecstatic acceptance speech (“It’s gonna be all right now, it’s gonna be all right!”), it looked as if he and Michael Jackson had been shopping at the same place for sunglasses. “We were,” he says with a laugh. “We were trying to be the same people.”

With the exception of his first album, 1982’s shimmering and still-resonant “Lionel Richie,” and his most recent, the exclamation point that is his 2012 country duets album, “Tuskegee,” Richie’s other eight solo studio albums can seem postscript to “Can’t Slow Down.” The album went on to sell more than 20 million copies and featured five Top 10 singles: “Penny Lover,” “All Night Long (All Night),” “Stuck on You,” “Running With the Night” and “Hello,” as well as the mesmerizing midtempo “Love Will Find a Way,” co-created with Greg Phillinganes. “Love Will” — sinewy, necessary — tethered Richie’s most buoyantly spectacular songs to the streets.

Aside from that Alabama twang and the infamous Motown polish, Lionel’s other solo songs have their roots not only in hits like the Commodores’ “Three Times a Lady” (recorded in waltz time) but in the masterful escapist pop of the oft-maligned Fifth Dimension (“Up, Up And Away) and the most soaring early hits from Earth, Wind & Fire, like “Fantasy” and “Devotion.”

What is the exquisite Commodores’ ballad “Zoom” (co-written by Richie and bassist Ronald LaPread) but a mourning and a yearning for flight toward a place of less pain? That “mighty glad you stayed” lifts “Stuck on You” from merely plaintive to trembling with humility. It’s the line everyone was waiting for at the Wynn’s Encore. People crave permission to say stuff like that, let alone sing it. And that’s what Richie, even now, still gives. If that’s not soul or blues, I’m not sure what is. Country music royalty Kenny Rogers knew: “Lady,” which Richie wrote for the Commodores, went to Rogers in 1980, and then straight to No. 1 on the pop charts.

That some of Richie’s songs are still mocked as devoid of soul reeks of a nudge to stay in the “R&B” (or even country) lane — when all of these lanes were invented to segregate sales charts, radio stations and record stores. To those who say (or used to say) that Richie “sold out” or that he’s “gushy” or, like folks said about him when I was in my teens, that he is “soft” — I say Lionel’s a rebel. He did and continues to do what the hell he wants to do.

Because “Can’t Slow Down” was a vibe shift. A precursor to the relentless and record-breaking popularity of Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson and Mariah Carey. Of MC Hammer and Boyz II Men. Lionel is not only well-aware of the pressures that come with changing a culture, he’s brokenhearted about how brutal the road is toward winning the game.

“I always,” he says, with the stiff guilt of survivors, “used to tease Michael and Prince and Whitney. Said, ‘OK, you guys are the hares, I’m the tortoise.’” Richie is almost back at the water fountain, eyes a-glisten with memory. “Father, help your children,” Richie sings on his “Jesus Is Love.” “Don’t let them fall by the side of the road.”

“And all of a sudden, I get a note from the frontline — ‘One of the hares fell before the finish line. The next hare tripped and fell before the finish line. Third hare — tripped and fell before the finish line.’”

HE WANTED HIS DAUGHTER NICOLE’S CHILDREN — Sparrow, 12, and Harlow, 14 — to call him G-Dad. But as Richie has said, the kids get to pick what they call you. So at the Wynn, Pop-Pop Lionel gives us old heads a proper thrill. Or perhaps just proof that we were once wild and young and deeply into the idea that music can solve hard things.

“All Night Long” is Richie’s encore, but “We Are The World” is the penultimate song of the night. And unlike some of his other hits, which he jogged through, Richie slows the tempo of “World.” Each line rings like a recitation. “There comes a time / When we heed a certain call / When the world must come together as one / There are people dying / Oh, and it’s time to lend a hand / To life / The greatest gift of all.”

Most people are singing along with Richie. But the lyrics feel more like a challenge than a call to love your neighbor. There’s a crackly undercurrent in the concert hall. Folks who have been grooving all night to Lionel’s every hit and every joke seem to wonder just where he is going with all this we-are-the-world business. Lionel, though, sings it out long and true. Such are our times that a huge hit calling for camaraderie and giving can ring like a revolutionary anthem.

Back at the Peninsula, I tell Lionel Richie that even with all of his awards and accolades, and even as beloved as he is as an “Idol” judge, things are not as they should be. I don’t like the tone many have taken about his work. But Richie is not entertaining my notions. He starts talking again about the Tuskegee Airmen.

“The United States didn’t send them a plane to practice in,” Richie says without rancor. “They had to build planes to practice in. People say, ‘Lionel, how does it feel being the first Black person to write a song for Kenny Rogers?’ No, no, no, no. There’s a guy named [Otis] Blackwell who wrote the records for Elvis Presley.” Otis Blackwell, a Black man from Brooklyn, wrote “All Shook Up,” “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Return to Sender.”

Lionel continues: “Elvis said, ‘Thank you very much.’ And Kenny Rogers said, ‘I couldn’t have done it without my friend Lionel Richie.’ What I’m saying to you is, I got the credit. How I look at this is, I stepped on the shoulders of those people who basically were invisible in American history. I came out of Tuskegee and made it. That’s my job,” says Richie. “That’s my job.”

Danyel Smith is the host of the Spotify Original show “Black Girl Songbook” and author of the forthcoming “Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.