Ronnie Spector’s swagger made her a rock ‘n’ roll immortal. It also saved her life

Even now, more than half a century after it came out, “Be My Baby” has the power to overwhelm.

One of the most intense pop records of all time, the Ronettes’ 1963 girl-group classic is a study in too-much: a quivering, trembling, throbbing little symphony pitched at such a high emotional register that the song made as much sense opening a Martin Scorsese movie about inner-city violence as it did a Patrick Swayze movie about forbidden romance.

Tune out the swooning strings and the madly thumping drums, though — focus instead on Ronnie Spector’s lead vocal — and what you hear in “Be My Baby” is something like total control.

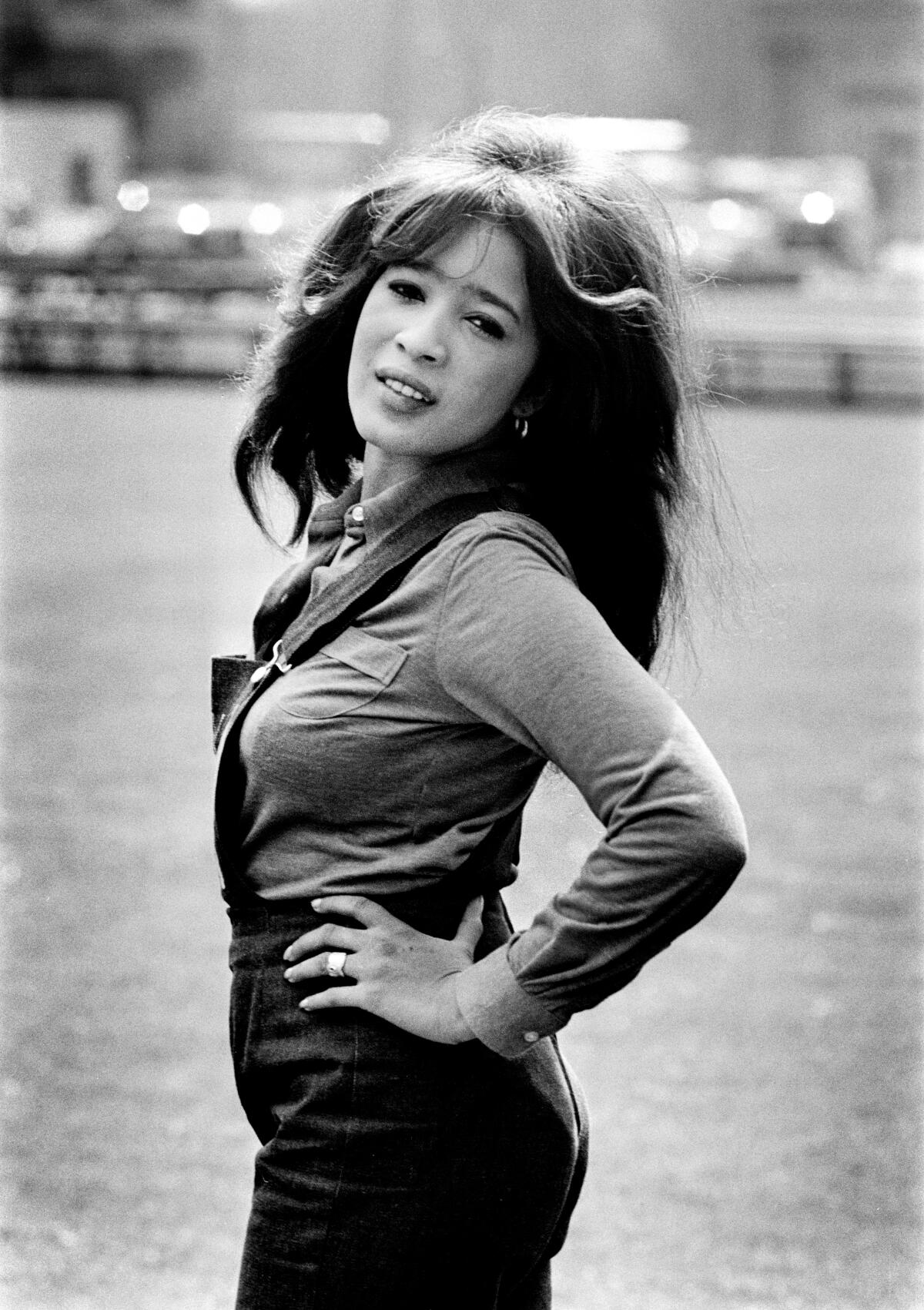

Yes, Spector, who died of cancer Wednesday at age 78, is singing about giving herself over to love; no, her performance is not uninterested in the ecstasy of abandon. But as captured in the slightly serrated edges and the swaggering forward thrust of her voice, this is a woman who knows what she wants and how to get it.

It’s right there in the song’s first couplet: “The night we met I knew I needed you so,” she recalls, landing on that final word with a gymnast’s precision. “And if I had the chance I’d never let you go.” She can already see the relationship with the guy she’s talking to, already imagine folks turning their heads on the street to catch a glimpse of what they’ve got.

Ronnie Spector, who sang such indelible 1960s hits as “Be My Baby” and “Baby, I Love You” as the leader of the girl group the Ronettes, has died.

As Veronica “Ronnie” Bennett lays out her vision — you’d call it a fantasy if her singing didn’t exude such certainty — the music continues to swell, the other Ronettes (older sister Estelle Bennett and cousin Nedra Talley) filling in the sound like a couple fills a new home with furniture; eventually, the song crashes to a stop for a second so everybody can regain their bearings.

Everybody but Ronnie, that is: She just picks back up after the drum break, keeping her New York subway train of a voice pointed toward eternity.

It’s no wonder, given the tune’s lasting popularity, that countless musicians have cribbed Hal Blaine’s iconic “Be My Baby” beat over the last few decades. (Among them: Billy Joel in “Say Goodbye to Hollywood,” the Jesus and Mary Chain in “Just Like Honey,” the Beach Boys in “Don’t Worry Baby,” which Brian Wilson wrote with the hope that Spector would perform it.)

But really, what choice did her admirers have? No one ever stood a chance of equaling Spector’s blend of yearning and grit.

Along with her sexy, street-smart look, the fortitude in Spector’s singing — in “Be My Baby” and in other mid-’60s Ronettes hits like “Baby, I Love You,” “(The Best Part of) Breakin’ Up” and “Walking in the Rain” — helped carve out space for fresh ideas about women in pop and in society. At a moment when girl groups were largely expected to fulfill conventions of decorum, hers was a voice of freedom that foretold her own liberation from Phil Spector, the producer-turned-husband-turned-tormentor who essentially imprisoned her at their home in Beverly Hills, as she wrote in her groundbreaking 1990 memoir, until she escaped barefoot in 1972.

“I can’t help it if I feel this way,” she sings in “Baby, I Love You” — real sorry-not-sorry energy in this one — while the best part of “Breakin’ Up” has to be the side-eye you can feel Ronnie Spector giving her boyfriend as she tells him, “It makes no difference who was wrong.” Few vocalists before her wielded switchblade attitude with so much charm.

Those who tried in her wake made her influence clear, from Joan Jett (who said Wednesday that Ronnie’s “mark on rock and roll is indelible”) to Amy Winehouse (whose “Back to Black” could’ve passed for a lost Ronettes album). A kind of survivor’s aura took shape around Ronnie that made her a hero to younger women, yet in an ironic twist fixed her image in pop culture in a way distinct from, say, Tina Turner, who’d also recorded with Phil Spector and who famously endured the abuse of her then-husband, Ike. Turner went on to dabble in various sounds and styles; audiences in the ’80s eagerly accepted her as a creature of her own design.

Ronnie worked steadily in the studio and on the road after the Ronettes — one overlooked highlight was a gutsy mid-’70s disco single, “You’d Be Good for Me” — but what connected with listeners was music that reaffirmed a familiar impression. There was her cover of “Say Goodbye to Hollywood,” with wailing accompaniment by Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band; there was a scrappy Joey Ramone-produced rendition of “Don’t Worry Baby” that finally realized Wilson’s fanboy dreams.

Most notably there was “Take Me Home Tonight,” the glossy and muscular Eddie Money single that brought Ronnie back toward the top of the charts in 1986. It’s about a guy trying to persuade a girl not to leave him; he’s throwing out every line he can think of — he can’t sleep, it’s too dangerous for her to walk home, he knows she wants to stay too — until at last he admits that he’s the one “frightened in all this darkness” and that he needs a “guardian angel” to protect him.

That’s when Ronnie swoops in, of course, to deliver her signature lyric as only she could — the sweet, scratchy, soulful voice of authority, still reassuring others even as she keeps herself safe.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.