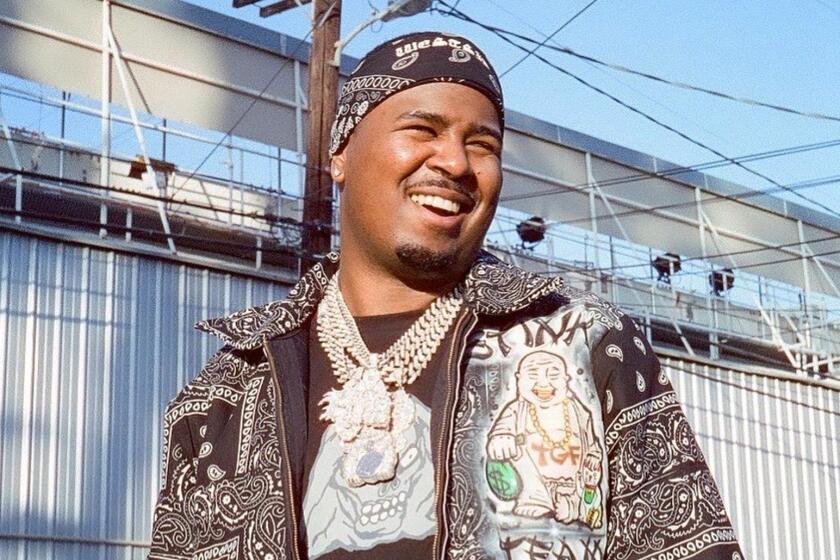

‘He deserved so much better’: L.A.’s hip-hop community mourns the loss of Drakeo the Ruler

Less than three months ago on a pleasant September night, Drakeo the Ruler sauntered onto the Novo stage in downtown Los Angeles, the gleaming diamond chains around his neck accentuating his regal stage name. Stepping through the black curtain while rapping his song “Too Icey,” his words were nearly overpowered by the crowd’s roar, his eyes likely blinded from the flood of phone lights before him.

Before he rapped a single bar, it was a special night: It was his first time on a Los Angeles stage since his release from jail in November 2020.

After spending two years in jail on a murder charge for which he was eventually acquitted, he languished for another 14 months at Men’s Central Jail while the former district attorney pursued charges of criminal gang conspiracy. Now, finally reunited with his fans, each syllable felt like the first day of spring after a winter of false hope and continued proceedings.

Drakeo the Ruler, 28, whose surrealist slang made him one of the most original stylists in L.A. hip-hop, died after being stabbed at a concert.

“To see him in all his glory, everyone there, camera phones up, singing his lyrics — it had been so overdue because of his legal trouble and COVID — so to finally see it happen was dope to watch,” said Victor Ulloa (better known as Rosecrans Vic), founder of Rosecrans Avenue, an L.A. hip-hop website and concert promoter. “It was a historic moment.”

On Dec. 18, the man born Darrell Caldwell was set to perform again at the Once Upon a Time in L.A. festival, until he was stabbed during a backstage altercation. Early the next morning, he was pronounced dead at age 28. Without him, there is now a gaping hole in the fabric of his city’s music that’s larger than the pile of uchies — a.k.a. Benjamin Franklins, or $100 bills — he stands over on the cover of his breakthrough mixtape “So Cold I Do Em.”

Drakeo the Ruler was a one-of-a-kind penman, eschewing traditional English for a coded language of references and surrogates that could fill its own dictionary. Over rattling drums and spine-chilling synths on his 11 albums and mixtapes, he muttered his sinewy parables in a muted tone, often with a creeping tremor as if an enemy might sneak into his recording booth at any moment.

He called it “nervous music.”

“I live a nervous life. I gotta look around and watch my back from police and these other [people] out here,” he told Jeff Weiss, veteran music journalist and longtime advocate for his freedom, in The Times in 2018. “[People] want to kill me. I can’t be driving around in $100,000 cars on the run, listening to soft-ass [music].”

Drakeo grew up in South Central L.A. and attended Washington High School in Westmont. Never very interested in school — he rarely made it three months without being kicked out, he said — he turned to music.

His first big break came in 2015 when Mustard, the producer behind L.A. ratchet music, heard his 2015 song “Mr. Get Dough” and remixed it with a feature from fellow L.A. rapper RJ.

Later that year, the track appeared on Drakeo’s debut mixtape, “I Am Mr. Mosely,” an early glimpse of what he could accomplish while still driven by Mustard’s piano-laden sound. By 2016’s “So Cold I Do Em,” he had come into his own, his flatlined flow shining on songs like the standout “Impatient Freestyle.”

Many imitated his style and attempted to conquer Los Angeles by following in his footsteps, either consciously or unconsciously. But his greatest battle was against the American justice system and against prosecutors who hemmed him up in solitary confinement while pursuing a murder charge and defining his rap group, the Stinc Team, as a gang to be feared rather than artists to be respected.

“He deserved so much better then, and he deserves so much more now,” said Erin Ryan, who formerly handled publicity for Drakeo at Audible Treats. “He pioneered nervous music, ushered in a whole new class of rappers trying to master that Drakeo sound.”

As he watched a new wave of local artists like Blueface and BlueBucksClan rise to prominence in his absence, he released a mixtape of old loosies and unreleased cuts titled “Free Drakeo” in March 2020. When that wasn’t enough, he picked up the phone to create what would become “Thank You For Using GTL,” produced by Terrence Hackett, a.k.a. JoogSZN.

The recording of the album was yet another test of patience for a man with little reason to have any left. Rather than rapping into a typical studio microphone, Drakeo recited his lyrics into the mouthpiece of a jail phone. On the other end, JoogSZN balanced a laptop on a cereal box while playing the beat for Drakeo on a Beats Pill speaker pointed toward the phone.

The 13 songs were recorded across 36 hours, each in one-hour increments, the time limit of the jail phone system operated by Global Tel Link (or GTL for short).

“Drakeo was more than music,” JoogSZN said. “He was a brother and one of my best friends. He lit up the room, he did things his way and provided for so many people. He was a mastermind. ... There will never be another Drakeo.”

With a Drake feature in tow on “Talk to Me” from his 2021 album “The Truth Hurts” and a primetime slot at Once Upon a Time in L.A., Drakeo’s profile was seemingly higher than ever. Now, his name is added to the uncomfortably long list of rappers whose voices were silenced before their time, while his friends and family are forced to reconcile with another loss in a year filled with too much grief.

“I appreciate your influence on me and the L.A. music scene in totality,” L.A. rapper Remble wrote on Instagram (Drakeo featured on his song “Ruth’s Chris Freestyle”). “Your name will most definitely live on forever.”

“He was stubborn but he knew what he wanted,” Drakeo’s brother and fellow Stinc Team member Ralfy the Plug wrote on Twitter. “He just wanted to see everybody winning and it seemed like everybody wanted to see him lose.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.