Marilyn Manson’s accusers detail his alleged abuse. ‘He’s so much worse than his persona’

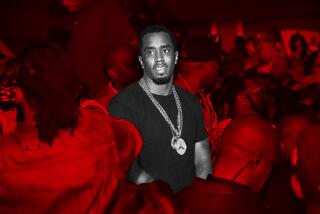

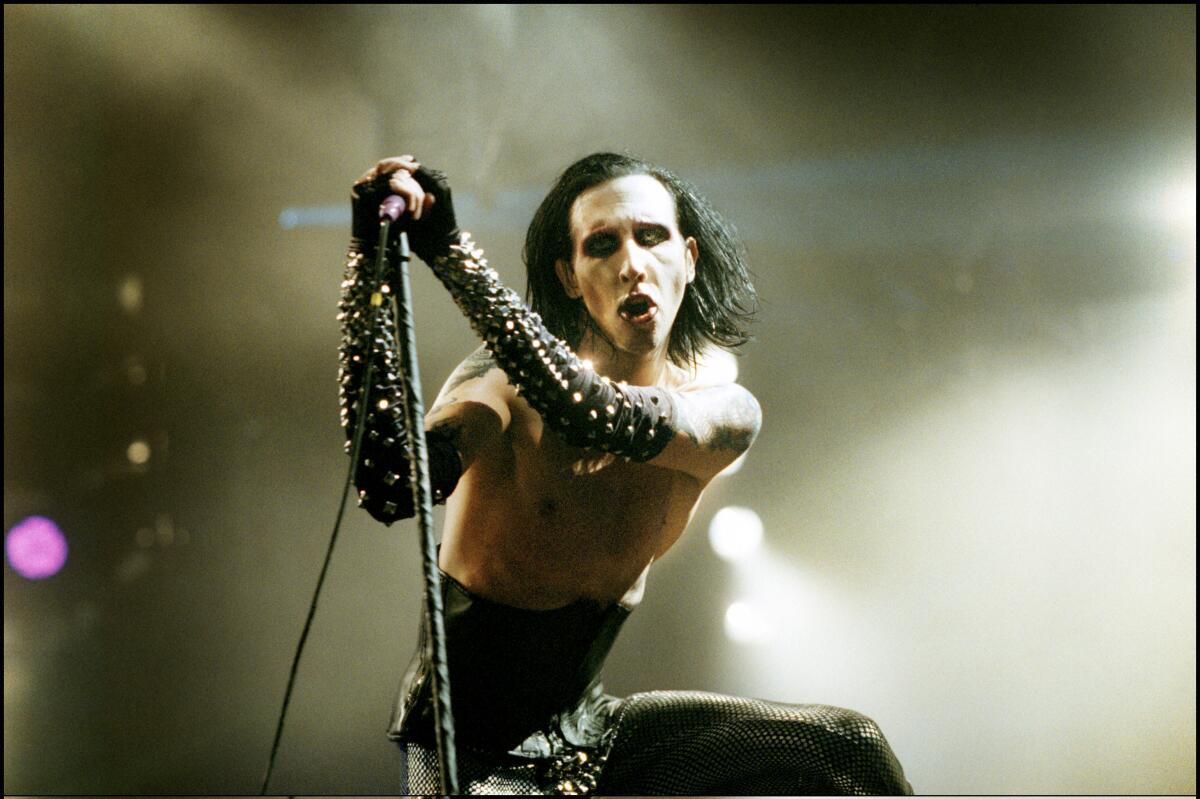

For three decades, goth rock singer Marilyn Manson reveled in his image as the ultimate pop-culture villain.

In U.S. District Court in downtown Los Angeles, the British-born actor Esmé Bianco is waging a legal battle to prove that Manson’s menacing persona was all too real.

Bianco’s federal lawsuit, filed April 30, alleges sexual assault, sexual battery and human trafficking beginning in February 2009, when Manson flew her to L.A. to shoot a video for his song “I Want to Kill You Like They Do in the Movies.”

The video never materialized. Instead, the 39-year-old says, over the course of four days, Manson locked her in a room, beat her with a whip and shocked her with electricity in his frigid home in Los Angeles.

Although the two established a sexual relationship later that year, the “Game of Thrones” star alleges in her lawsuit that she tolerated a number of abuses, including forced labor, sleep deprivation and rape, after Manson offered to help secure a U.S. work visa, then threatened to obstruct the process when she didn’t meet his demands.

Manson, whose legal name is Brian Hugh Warner, has said the claims are “horrible distortions of reality.” His attorney John Snow petitioned to dismiss the case at a hearing in August, arguing that Bianco’s claims had expired under California’s statutes of limitations for domestic violence and sexual assault.

In 2018, California’s statutes of limitations for civil actions were extended from three to 10 years after the last alleged act of sexual assault. The new law allows victims to pursue claims up to three years after “the plaintiff [discovers] that an injury or illness resulted from an act.” Judge Fernando L. Aenlle-Rocha allowed the case to move forward, saying the alleged misconduct could fall within the statutes of limitations.

“A reasonable jury could find that the effects of Warner’s alleged unconscionable acts, including the perceived threat to Plaintiff’s safety, immigration status, and career, persisted years after her last contact with Warner,” Aenlle-Rocha ruled in October.

Bianco’s suit, the furthest along among four civil suits pending against Manson, could take years to resolve. But it has already changed how the world sees the artist.

“People pass it off as ‘Oh, he’s eccentric,’ or ‘What the hell was she expecting?’” Bianco told The Times. “If only it was a stage persona. He’s so much worse than his persona.”

Since February, multiple women, including Manson’s former fiancée, actress Evan Rachel Wood, have accused the infamous rocker of misconduct. He has been dropped by his record label, Loma Vista, and agency, CAA.

Manson’s attorney Howard King said in a statement: “Mr. Warner vehemently denies any and all claims of sexual assault or abuse of anyone. These lurid claims against my client have three things in common — they are all false, alleged to have taken place more than a decade ago and part of a coordinated attack by former partners and associates of Mr. Warner who have weaponized the otherwise mundane details of his personal life and their consensual relationships into fabricated horror stories.”

Court records and emails reviewed by The Times along with nearly two dozen accounts from former partners and colleagues portray Manson as someone who used his reputation as a transgressive artist to mistreat and isolate women drawn to his boundary-pushing music.

Some who knew and worked closely with Manson describe him as a “romantic” and sensitive person whose art could be misunderstood and say that they never witnessed abuse on his part. Yet others interviewed by The Times argue that a revolving door of bandmates, employees and executives ignored or failed to prevent his misconduct.

The claims against Manson and other high-profile music industry figures such as Russell Simmons have prompted an examination of the music industry and its permissiveness toward artists who pursue significantly younger fans. Simmons has denied claims of women who accused him of sexual misconduct.

The making of Marilyn Manson

Long before he became one of America’s most notorious rock musicians, Manson was Brian Warner, a gawky metalhead from Ohio who dreamed of revenge against his schoolyard tormentors. He fused two names — that of Hollywood icon Marilyn Monroe and white supremacist cult leader Charles Manson — into a persona fit for a horror film.

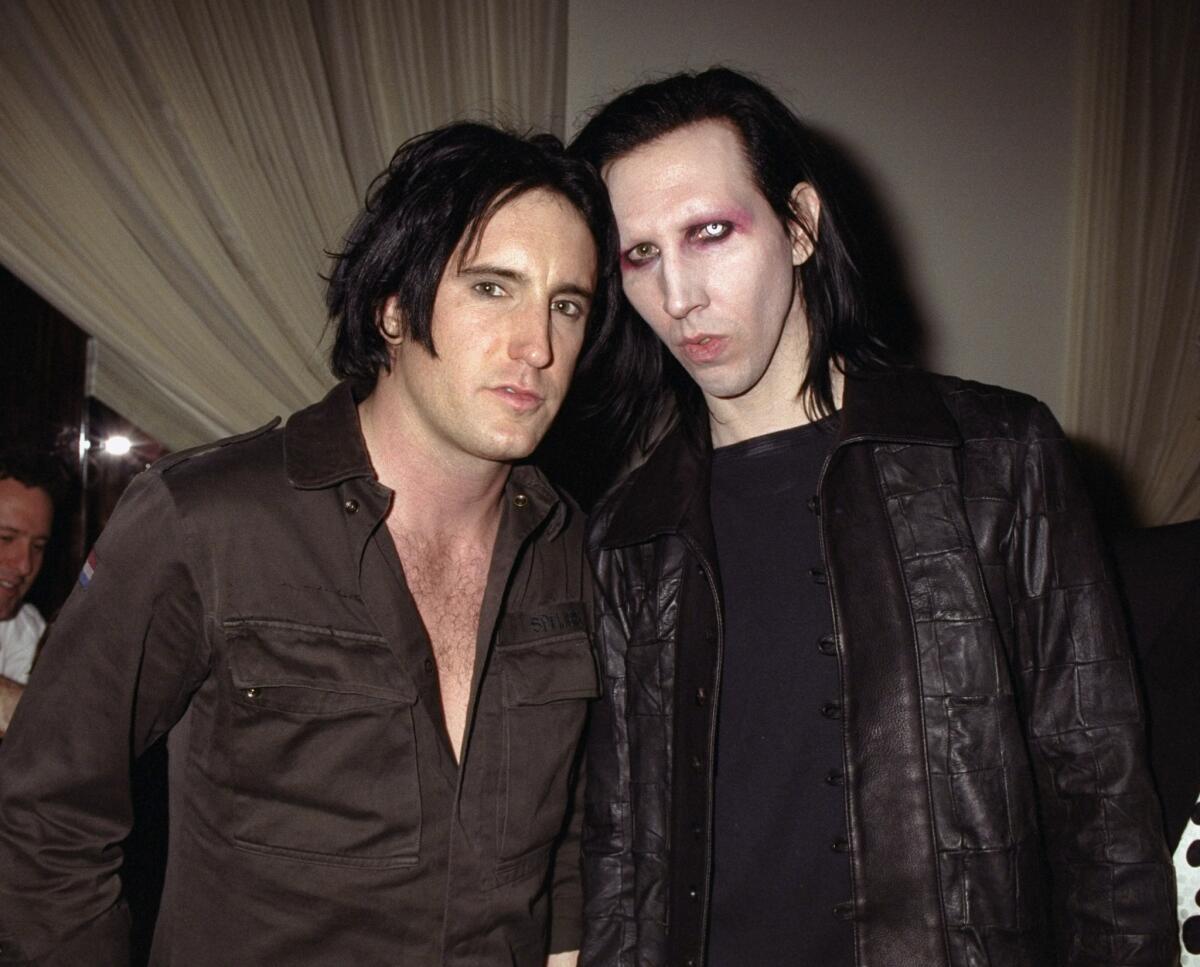

On the 1994 single “Lunchbox,” Manson recalls fending off bullies by swinging an aluminum Kiss Army lunchbox. “I want to be a big rock and roll star. … So no one f— with me,” he sings. Manson, then 25, was signed to Nothing Records, an imprint of Interscope helmed by Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor.

On platinum albums including “Antichrist Superstar” and “Mechanical Animals,” Manson cultivated a character — part Alice Cooper, part androgyne glam monster — that antagonized the religious right and enraptured teenagers. Throughout his career, Manson has had 10 top 10 LPs and played in festivals all over the world. Conservative groups scapegoated him as the alleged inspiration for the Columbine High School massacre. His shows were frequently picketed, and he received death threats.

But his fans, ostracized by peers for being too weird, too poor or queer, felt understood by the macabre, disillusioned outsider.

Alison, who asked that her last name not be used, told The Times she was around 16 when she saw Marilyn Manson at Madison Square Garden in the mid-’90s. She and her friend Jeanette Polard were so enthralled with Manson that they carved his name into their chests with blades before the show.

“I heard that night Manson asked, ‘Are those girls actually crazy, or are they crazy like us?’ ” she said.

The two became part of Manson’s iconography as “The Slashers” or “The Slice Girls,” appearing in photos and documentaries about him.

“He was always the cleverest, smoothest guy in the room,” Alison said of Manson then. “It was a great time in my life, but now it’s been really sullied. I have to reframe him in my mind.”

There were warning signs in the early years of Manson’s career.

In his 1998 memoir, “The Long Hard Road Out of Hell,” co-written with Neil Strauss, Manson stoked controversy when he claimed to have beaten, choked and spit on his mother as a teen; described a plot to kill a woman named Nancy; and recalled draping a deaf fan in meat and urinating on her at a recording studio. “It was more of a living meat sculpture,” he wrote.

The Times’ music editor, Craig Marks, filed assault and harassment charges against Manson in November 1998 that were later dropped.

He said the artist’s bodyguards choked him after a concert in New York, when Marks was the executive editor at Spin, because Manson was angry about not being featured on an upcoming cover of the magazine.

Prior to the assault, Manson told Marks he could kill him, his family and “everyone you know,” according to a lawsuit Marks filed against the musician. The suit was settled.

In 2007, ex-Manson keyboardist Stephen Gregory Bier Jr. (a.k.a. Madonna Wayne Gacy) sued Manson for allegedly misappropriating band funds to buy Nazi paraphernalia, human-skin masks and a child’s skeleton to display in his home. The suit was settled out of court.

Manson’s star waxed and waned in the 2000s. Burned out on his commercial music career, he wrote and began directing a film titled “Phantasmagoria: The Visions of Lewis Carroll,” which was later abandoned. But his career rebounded in recent years; he signed to acclaimed indie label Loma Vista and landed roles on TV shows such as “Sons of Anarchy,” “The New Pope” and “American Gods.”

Manson previously had high-profile relationships with celebrities, including movie star Rose McGowan, followed by burlesque idol Dita Von Teese, whom he married in late 2005. Von Teese filed for divorce a year later “due to infidelity and drug abuse.” Both women denied experiencing any abuse by Manson. Last year, he married his longtime girlfriend, photographer Lindsay Usich.

In February, Wood, who dated Manson off and on between 2007 and 2010, rocked the music industry by accusing him for the first time of abuse. (She previously had attested to surviving domestic violence without identifying the alleged perpetrator.)

“He started grooming me when I was a teenager and horrifically abused me for years,” the now-34-year-old star of HBO’s “Westworld” wrote in an Instagram post.

Manson met Wood at a party in 2005 and sought to cast her in “Phantasmagoria.” The two made their relationship public shortly after Manson’s 2007 divorce, when he was 38 and Wood was 19. She starred in his 2007 music video for “Heart-Shaped Glasses (When the Heart Guides the Hand),” a cheeky nod to Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita,” and accompanied Manson on tour. “I met somebody that promised freedom and expression and no judgments,” she told Rolling Stone in 2016.

But behind the scenes, Wood said in February, “I was brainwashed and manipulated into submission.”

A representative for Manson said, “Mr. Warner never isolated Ms. Wood from her family and friends.”

In a 2009 interview, Manson told Spin that during a period of separation, he phoned Wood 158 times and cut himself with a razor blade for each call. “I have fantasies every day about smashing her skull in with a sledgehammer,” he said.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has confirmed that it is investigating allegations of domestic violence involving the musician between 2009 and 2011. Investigators did not specify who made the allegations against Manson, but the dates coincide with his relationships with Wood as well as Bianco.

Manson also faces two counts of misdemeanor assault for a 2019 incident at a New Hampshire concert. The case is ongoing; Manson has pleaded not guilty.

Wood declined to comment for this story.

In a federal lawsuit filed in Los Angeles in June, model Ashley Morgan Smithline alleged that Manson assaulted her. While she was modeling in Thailand in 2010, she said, Manson offered her a part in a film he planned to produce. He flew her to Los Angeles that November.

“He asked me to bring him Nazi memorabilia,” Smithline wrote in an Instagram post. “It felt so wrong because I’m Jewish.”

Smithline said that one night she “awoke from unconsciousness with her ankles and wrists tied together behind her back and Mr. Warner sexually penetrating her.”

On a separate occasion, the lawsuit states, Manson forced Smithline onto his bed, put a pillow over her face and began cutting her shoulder, inner arm and stomach; she also alleged Manson “carved his stage name initials into Ms. Smithline’s thigh, leaving the letters ‘MM’ visible to this day.”

Manson has disputed Smithline’s claims, saying his relationship with her lasted less than a week in 2010. “There are so many falsehoods within her claims that we wouldn’t know where to begin to answer them,” he said in a June statement.

Another woman, who is unidentified, said in a May lawsuit filed in L.A. County Superior Court that Manson raped her in 2011 inside his blacked-out Los Angeles home. According to the lawsuit, Manson “bragged that he would ‘get away with it’ if [he] murdered her.”

The plaintiff said she feared for her life when Manson forced her to watch “Groupie,” a never-released short film. In it, Manson is said to have held a young woman at gunpoint, whipped her and forced her to drink urine on camera.

Manson’s ex-girlfriend Pola Weiss, who appeared in the 1997 video for “Long Hard Road Out of Hell,” has said she played the woman in “Groupie” when she was 19. Two former employees supported claims that “Groupie” was a staged collaboration among Manson, Weiss and filmmaker Joseph Cultice.

Cultice did not respond to requests for comment.

A representative for Manson said: “It was not a home video. Weiss was not only a willing participant in the film but also a creative collaborator on it.”

Manson has denied assaulting the unidentified plaintiff or anyone else, calling it part of a coordinated “attack to turn inconsequential details about Mr. Warner’s art and private life into circumstantial cudgels to destroy his life and career,” the representative said.

Multiple sources, including the unnamed plaintiff, say Manson deliberately intimidated women by playing “Groupie.” She declined an interview with The Times, stating through her attorney that “she reasonably fears retaliation from Manson’s fans, who have posted vicious attacks against his victims on social media.”

Claims of abuse from former employees

In a May lawsuit filed in L.A. County Superior Court, Manson’s former personal assistant Ashley Walters described a hostile work environment.

Manson first approached Walters, a photographer, on social media in March 2010, seeking artistic collaboration. By August, he had hired her as his personal assistant. In her suit, she alleges she was made to transport narcotics overseas, “treated like property” and sexually offered to his famous friends.

Walters, 37, told The Times that Manson, who has often experimented with Nazi imagery in his work, coerced her into participating in antisemitic and misogynistic art collaborations. This included asking her “to remove all of her clothing except her underwear and a Nazi jacket” and smudging her lipstick because he liked to style women “like they just got raped,” she said.

“People are scared [to speak] because he gets collateral on you,” Walters said. “There was this illusion of creative freedom. He’d say, ‘There’s no racism here. You can say the N-word,’ and if you don’t, then you’re censoring.”

Walters stated in her lawsuit that Manson threw “a prop skull so hard at Wood that it left a large raised welt on her stomach.” Walters, and multiple sources who toured with the band, said that women were bullied about their weight and given cocaine in lieu of food.

In emails obtained by The Times, dated May 13 and May 15, 2011, Manson sent Walters a photograph of knife wounds on Bianco’s torso, with the subject line: “See what happens?”

Manson “would rein it in like, ‘Oh, you’re my sister. We’re family,’” Walters said in an interview. “He manipulates the whole thing just to keep people scared and isolated.”

In 2011, stylist Love Bailey said photographer Lionel Deluy asked her to style a shoot at Manson’s home studio in L.A. Bailey, then 21, “initially jumped at the chance,” she told The Times.

But inside Manson’s studio, “he pulled a gun on me and said ‘I don’t like f—s,’ ” said Bailey, a trans woman, using an anti-LGBTQ slur. “I thought, ‘He’s too famous to kill me,’ but then he laughed and pulled the trigger. My life flashed before my eyes.”

The gun didn’t fire, and Bailey fled the house.

A former modeling agent and longtime friend of Bailey’s confirmed that Bailey recounted the incident to her and other colleagues immediately afterward.

Deluy did not respond to a request for comment. A representative for Manson said the musician “does not recall witnessing any of the events described by Bailey.”

An artist of Manson’s stature has a close-knit team — managers, bandmates, label executives — to attend to his needs and buff his reputation. Some in Manson’s inner circle wish they’d spoken up sooner or wondered why few others did.

Tony Ciulla, Manson’s manager since 1998, resigned this year. Multiple people who worked with Manson said Ciulla was aware of the singer’s alleged misconduct.

Ciulla was named as a defendant in a prior version of Bianco’s lawsuit. Bianco’s attorney said “the suit was later amended to remove Tony Ciulla after the matter was resolved.” Ciulla declined to comment.

Tom Whalley, the head of Manson’s former label Loma Vista Recordings (and a former Interscope president), said:

“In light of the disturbing allegations by Evan Rachel Wood and other women naming Marilyn Manson as their abuser, Loma Vista ceased to promote his newest album on February 1, 2021. Loma Vista has also decided not to work with Marilyn Manson on any future projects. Loma Vista takes these allegations very seriously. However, we have no knowledge of the situations that led to these claims.”

Reznor, whom Manson described as joining an assault of an intoxicated fan in his memoir, says he cut ties with Manson nearly 25 years ago. In a statement, Reznor said “the passage from Manson’s memoir is a complete fabrication. I was infuriated and offended back when it came out and remain so today.”

Dan Cleary, former personal assistant to Manson, alleged that Manson had sucker punched him in the head during a show in South Korea and mistreated Wood while on tour in 2007 and 2008.

A representative for Manson said that “the context is that this allegedly happened onstage at a rock ’n’ roll concert.”

In an interview, Cleary expressed regret about not speaking out sooner; he said he kept quiet after Manson bought him plane tickets to his stepmother’s funeral in 2007. He returned to work for Manson from 2014 to 2015.

“If you show someone a little bit of love and a lot of violence or mental anguish, a lot of people will choose to focus on that little bit of love,” Cleary told The Times. “People like me turned a blind eye.”

Others said a fear of reprisal, coupled with Manson’s occasional acts of benevolence, kept them from voicing their discomfort.

“You laughed and looked the other way because you were petrified of losing your job or incurring his wrath,” said someone who toured with Manson in the 2000s. “Sometimes it was exciting; it was sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll. But then it went to extremely darker s—.”

Some former associates say they live in fear of Manson. Several people, including Bianco, cited the 2017 music video for “We Know Where You F— Live,” which sees Manson and a group of nuns approaching a family with automatic weapons before sexually assaulting the parents in front of their daughter. “They won’t even recognize your corpse,” Manson sings.

Others, such as Manson’s former personal assistant Paula Baby, counter those narratives. “He’s a very kind, sensitive person,” she said in an interview, even if “co-dependent.”

Now an actor and model, Paula — Baby is a stage name — first met Manson as a 17-year-old fan during his 2002 gallery opening in Hollywood. (“I cried my eyes out,” she said.) In October 2005, he offered her a job managing the home he shared with Von Teese in Chatsworth.

Paula rarely saw Von Teese before their 2007 divorce. It was around this time that Manson’s mother began exhibiting symptoms of dementia, Paula said, “and he doesn’t fare well being alone.”

Paula stopped working for Manson in late 2009. She said that he never behaved violently in her presence and that she returned to assist him from 2012 to 2016.

“I think he related to [bondage, dominance, sadism and masochism] more as an artistic aspect or what it represented,” said Paula. She recalled the “Violet Wand,” a shock device mentioned in multiple allegations, as a low-voltage antique he kept locked in a curio cabinet — along with relics from World War II. “I find it hard to believe that he would be capable of the physical abuse [the lawsuits] describe.”

Changing the law to protect victims

Even before the civil lawsuits were filed, Manson’s accusers helped further new domestic violence legislation in California.

Wood testified before the U.S. House in support of the Survivor’s Bill of Rights in the States Act in 2018.

“It started slow but escalated over time, including threats against my life, severe gaslighting and brainwashing, [and] waking up to the man that claimed to love me raping what he believed to be my unconscious body,” Wood said in her testimony.

Wood said she tried to pursue legal action against Manson but was thwarted by the statutes of limitations.

She advocated for California’s Phoenix Act — which extends California’s criminal statutes of limitations for domestic violence crimes from one year to five — as did Bianco.

Bianco alleged gruesome experiences with Manson — then unnamed — before the California Assembly Public Safety Committee. Bianco met Manson in 2005 when she was an actor in London.

“He knew that I was easy prey,” Bianco told the committee in 2019. “I had neither power nor control over my life.”

The law was enacted that year.

“The #MeToo movement, [and the] many women who came forward, put the issue on the political agenda, as it should be,” said David Sklansky, a law professor at Stanford and author of “A Pattern of Violence: How the Law Classifies Crimes and What It Means for Justice.”

California state Sen. Susan Rubio, author of the Phoenix Act, has also written legislation to add “coercive control” as a violation of the California Family Code and allow abuse victims to report and testify remotely.

“Coercive control isolates victims, manipulates them and surveils them … but it’s not often seen as abuse,” Rubio said. “Now we understand the psychological trauma of it and how long it takes to report.”

Rubio said she has also formally submitted a request to the FBI to open an investigation into Manson’s conduct.

“All my clients spoke to law enforcement about their dealings with Mr. Warner, and the investigation is ongoing,” said Jay Ellwanger, attorney for Bianco and Smithline. “But when my clients file civil lawsuits, they’re taking ownership of the situation themselves and not leaving it to other people to pursue justice.”

In light of the allegations, Manson has since appealed to a new demographic for redemption, albeit one he long scandalized: Christians.

The night before Manson’s August hearing, Kanye West invited Manson and rapper DaBaby, who was criticized for making homophobic statements, to appear at a Chicago listening party for West’s album “Donda.”

“Guess who’s going to jail tonight? God gon’ post my bail tonight,” they sing on West’s track “Jail Pt. 2.”

Dressed in white robes, Manson returned to West’s side Oct. 31, this time for a gospel-themed “Sunday Service” concert with guest Justin Bieber.

Even if Manson is welcomed back into the music industry, his accusers remain hopeful that their stories could spark lasting change.

“He’s been supported professionally by an entire industry and a ‘code of the road,’ ” Bianco said. “There are so many men like him, and for some reason that reckoning hasn’t come yet.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.