Jesus, drugs and rock ’n’ roll: How an O.C. hippie church birthed contemporary Christian music

The birth of contemporary Christian rock and pop music in America can in part be traced to a vision received by a 17-year-old runaway from Costa Mesa named Lonnie Frisbee.

After stripping naked and taking LSD in 1967 near Tahquitz Falls outside of Palm Springs, the young man called to God.

As water from the falls crashed, Frisbee, who wore his hair and beard like the archetypal Jesus Christ, saw himself standing beside the Pacific Ocean, Bible in hand, staring out at the horizon. But instead of water, the sea was filled with lost souls crying out for salvation.

“God, if you’re really real, reveal yourself to me,” Frisbee, who died of AIDS in 1993, later recalled pleading. “And one afternoon, the whole atmosphere of this canyon I was in started to tingle and get light and it started to change — and I’m just going, ‘Uh oh!’”

This lesser-known chapter in Southern California music history provides the genesis of “The Jesus Music,” a new documentary that traces the contemporary Christian music movement birthed at Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa and similar pockets of divinity dotting the country.

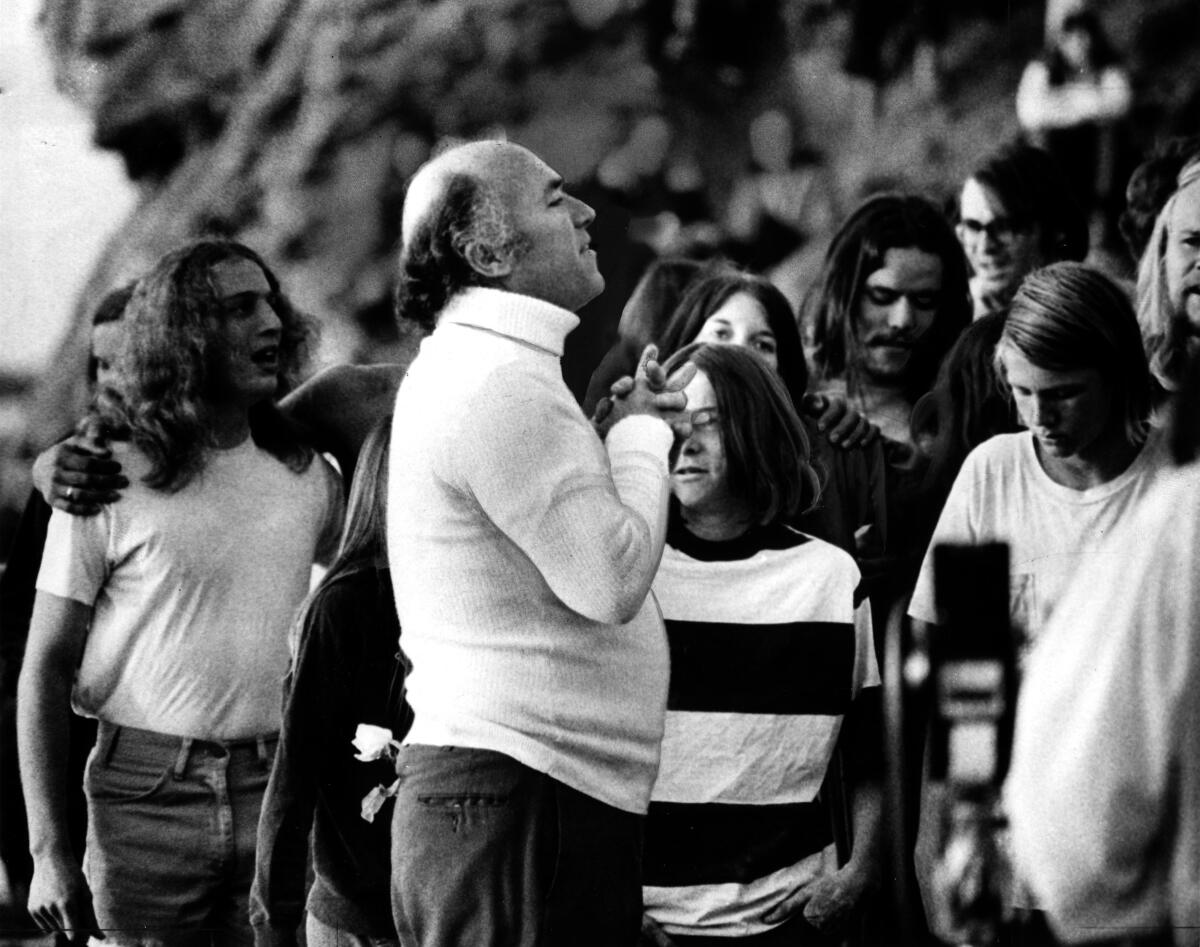

Within a year of that vision, the bell-bottomed messenger Frisbee was converting hippies alongside a bald fire-and-brimstone preacher named Chuck Smith and transforming Calvary Chapel — which The Times described in a 1970 story called “Zapped Fundamentalists” as “a small church of glass, brick, stucco and wood” — into a haven for touched-by-the-spirit bands such as Love Song, Gentle Faith, Blessed Hope and Children of the Day.

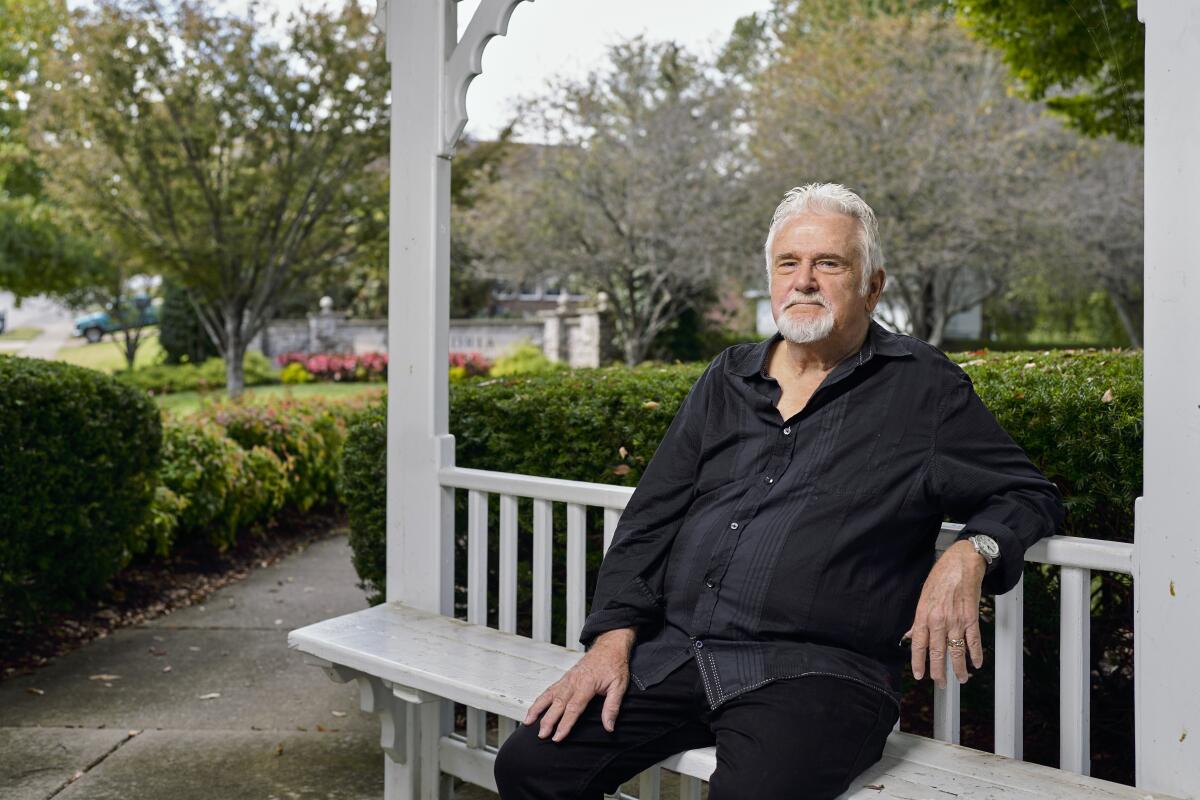

“We were models for how you could use drums and guitars in church and still have it be godly,” says Love Song co-founder Chuck Girard.

Directed by Nashville-based sibling team the Erwin Bros., “The Jesus Music” examines how the spirit of the times, a rush of faith-filled creativity and the emergent “Jesus People” movement begat a multimillion-dollar industry fueled by devotees eager to support their blessed messengers. The documentary, which premiered in theaters Friday and grossed an impressive $560,000 over the weekend, includes interviews with Girard and his Love Song bandmate Tommy Coomes; contemporary Christian stars Amy Grant, Kirk Franklin, TobyMac of DC Talk, Lecrae and Michael W. Smith; and volumes of archival footage.

“There’s just something so pure about where it all started,” says co-director Jon Erwin. “There wasn’t really an industry or an agenda behind it. Just a bunch of hippie kids that experienced something and gathered in masses to sing their songs.”

Though “The Jesus Music” moves far beyond Costa Mesa to tackle issues of race, morality, sin and redemption, its opening canto beams light on a long-gone music community 50 miles south of Laurel Canyon. There, during the same period Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, Frank Zappa and the Byrds were becoming famous, a half-dozen Calvary Chapel bands united in 1971 to create “The Everlastin’ Living Jesus Music Concert.”

Released on Chuck Smith’s new Maranatha! Music label and costing about $4,000 to produce, the album went on to sell more than 200,000 copies. Fifty years later, “The Everlastin’ Living Jesus Music Concert” is considered the Big Bang of contemporary Christian music — a collection of folk-inspired soft rock that, as it eased its way onto youth-group turntables across the country, cast a spell over Jesus-loving, mostly white baby boomers amid a generational shift.

“When I first heard that Maranatha record, I couldn’t get enough of it,” Christian singer Michael W. Smith says in “The Jesus Music.” “This thing called ‘Jesus Music,’ which exploded in Southern California, somehow found its way [to] my hometown, and it changed my life.”

“LSD was sort of a life-changer for me,” says Chuck Girard.

Like Lonnie Frisbee, Girard was unanchored and experimenting with drugs in the late 1960s.

“It opened up a bridge between the natural world and the spiritual world,” the Love Song singer-songwriter says by phone from his Nashville home. “As a Christian, I now consider it a counterfeit experience, but it’s very real when you’re going through it.”

California was drenched with LSD in the late 1960s, and Orange County was no exception. Laguna Beach, where many Calvary Chapel hippies were living, was haven to a bunch of acid-heads known as the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. Operating under the belief that LSD should be free, they developed ritualized trips and distributed it and pretty much every other drug at a boutique called the Mystic Arts World.

Girard, who recently published a memoir, “Rock & Roll Preacher,” recalls cruising the California coast to “pick up hitchhikers along Pacific Coast Highway to get free drugs because they’d be carrying a bag of weed or whatever.” On one such adventure, they ferried some fellow travelers who asked, “Hey man, do you guys know Jesus? We found Jesus. We go to Calvary Chapel.”

Born in downtown Los Angeles, Girard first earned major attention as a singer in the mid-1960s L.A. band the Hondells, one of producer-songwriter Gary Usher’s many hot rod-related projects. In 1964, the band’s version of Brian Wilson’s “Little Honda,” featuring Girard on vocals, peaked at No. 9 on the Hot 100.

But an unfulfilling, acid-fueled existence had left him rootless and dispirited. Searching, Girard and a few musician friends formed Love Song in 1969 as a way to address life’s big questions. He recalls this period as a “big mix of drugs and the Bible and Eastern philosophies — trying to check out what life was all about.” As the clique “started to land on the Bible more than anything,” Girard and his bandmates made the trip from their place in Laguna Beach to bear witness with Frisbee.

The hippie’s skills behind the pulpit were undeniable. “Lonnie did not have any executive abilities particularly, but he certainly was a major player in attracting the hippies and the beach-bum types,” explains Larry Eskridge, author of “God’s Forever Family: The Jesus People Movement in America.” Frisbee tied bells to his blue jean cuffs so he jangled when he walked, Eskridge continues, and “really stood out as different. He emphasized signs and wonders and miracles.”

After one particularly inspirational evening with Frisbee at Calvary, Girard had his literal come-to-Jesus moment, one that has informed his life ever since. Filled with fervor, Girard recalls thinking, “Wouldn’t it be cool if we played here? Then they’d have a band that looked like Pink Floyd and a preacher that looked like Jesus.”

But Smith, a Bible-thumping conservative, was wary. Before Frisbee, he’d had no time for California long-hairs, Smith told The Times in the early 1970s. “My feeling was, ‘Dirty hippies. Why don’t they take a bath?’” The church was growing, though, and Girard and his Love Song bandmates Jay Truax and Tommy Coomes convinced Smith to listen to them play.

In the sanctuary, they offered “Welcome Back,” a breathtaking Beach Boys-inspired production about a fallen believer returning to God. Hearing the song, Smith later wrote, “The Holy Spirit just touched my heart. I began to weep, and I hadn’t even been anywhere!”

The minister asked Love Song to play at that evening’s Frisbee-led youth night — “like heaven for us,” recalls Girard — and not long after, Girard started production with an engineer at a local studio on the songs that became “The Everlastin’ Living Jesus Music Concert.”

Within two years, Love Song would play as part of the Billy Graham-co-signed Explo ’72 at the Cotton Bowl in Dallas before an estimated 75,000 people. At the time, the New York Times declared it “the largest religious camp meeting ever to take place in the United States.”

Those vivid scenes drew the Erwin Bros. to the story of Calvary Chapel’s role in Christian music history, says co-director Andrew Erwin. He cites the famous Time magazine cover from 1971, emblazoned with the words “The Jesus Revolution,” as an early window into the Jesus People movement and music. “It blew me away in this all-roads-lead-to-Rome way. So much came out of that movement and out of Calvary Chapel, including Christian music.”

Six-time Grammy Award-winning singer Amy Grant first heard “The Everlastin’ Living Jesus Music Concert” as a preteen at some friends’ house in Nashville. “We would just sit in front of their turntable,” Grant recalls on the phone from Nashville. Soon she was part of the youth group and dabbling in music. “I wrote my first song because I was like, ‘God has a real PR problem in the conservative world because people think it’s a cultural choice instead of this adventure.’”

Not that Nashville was short on musical salvation. Word Records, founded in Waco, Texas, in 1951, helped spread a Southern-style evangelical message to the masses — and released Grant’s 1977 self-titled debut on its Myrrh Records subsidiary.

It was a distinctly different music from the Black gospel sound born in Southern Baptist churches, which laid the foot-stomping foundation for early rock ’n’ roll. Christian rock and pop artists of the ’70s, including Girard, Grant, Larry Norman, Phil Keaggy, the All Saved Freak Band and Mustard Seed Faith, liked to say that, since rock ’n’ roll was born in the church, they were merely facilitating its return.

Or, as Norman argued in his 1972 song of the same name, “Why should the devil have all the good music?”

The charismatic, enigmatic rock singer and songwriter Norman, who spent the late 1960s canvassing Hollywood Boulevard for converts, signed with Capitol Records to release 1969’s “Upon This Rock,” regarded as the first Christian rock album. “Upon This Rock,” though, tanked and Capitol dropped him.

Calvary bands Love Song, Gentle Faith and Children of the Day had little concern for Capitol-sized sales numbers, and didn’t yet have the connections to make a play for the mainstream. But Eskridge says that grass-roots structures were developing to support the emerging Jesus People movement.

“Maranatha put together their own little distribution networks, selling albums out of the back of vans and eventually going to mail order and linking up with rudimentary religious-music distributors and labels,” he explains. At the time, conservative Protestants, evangelicals and fundamentalist Pentecostals were on the other side of the cultural divide, he adds, specifying that “there was an element of the racist view that anything associated with jazz or those sorts of music was undesirable.”

A second compilation, “Maranatha! 2,” was released a year later, in 1972, and soon the mainstream came calling. Rolling Stone flew photographer Annie Leibovitz to take photos for a feature. Life magazine gave the movement a cover story. Executives from major labels wooed Love Song.

By then, Frisbee had moved on from the Calvary flock too, but not voluntarily. The preacher had been having sexual encounters with men, experiences that started when he was a teen. Though Smith had learned to tolerate dirty hippies, homosexuality was, in his words, “the final affront against God.” Grilled, Frisbee acknowledged his dalliances. Smith still gave him the boot. Frisbee moved to another ministry, the Vineyard, to evangelize. He wrestled with his sexuality for the rest of his life.

For Grant, holding the album “The Everlastin’ Living Jesus Music Concert” during her interviews for “The Jesus Music” offered an electrifying blast back in time. “It was everything coming out of the Maranatha community. And in my mind, it was everything coming out of Southern California. It was Love Song. It was Chuck Girard. It was Second Chapter of Acts. It was that whole scene.”

“That whole scene” remains a presence in Southern California, even if the musicians moved on. Smith disciples Greg Laurie, Skip Heitzig, Mike MacIntosh and Raul Ries have started more than 50 megachurches and Bible schools, according to Christianity Today, as well as a radio network.

Smith and Calvary Chapel Costa Mesa continued to thrive in the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2007, an explosive report in Christianity Today accused the church of being “dangerously lax in maintaining standards for sexual morality among leaders,” including covering up one of its pastors’ alleged statutory rape of another minister’s 15-year-old daughter. After Smith died in 2013, his son-in-law, Brian Brodersen, assumed control of the church.

By then, the Calvary Chapel movement had evolved into a loosely connected group of more than 1,700 independent, self-governing churches around the world. This past Sunday at Angel Stadium of Anaheim, Laurie’s Calvary Chapel-affiliated Harvest Christian Fellowship held one of its regular Harvest Crusades. The 45,000-capacity venue was packed.

Girard went solo in 1975 and became a certified star on the Christian music circuit. Televangelist Jimmy Swaggart — whose musician-cousins Jerry Lee Lewis and Mickey Gilley have wrestled with sin and salvation their entire lives — used Girard’s lovely 1975 ballad “Sometimes Alleluia” as his theme song. “I know that’s maybe not the greatest credit anymore, but it was pretty cool at the time,” says Girard.

Director Jon Erwin says that he wrapped the project with a profound respect for the Calvary musicians, whom he called “people who didn’t hear anything that sounded like them, and fought really hard to have their voices represented. To me, that’s incredibly rebellious and incredibly romantic.”

He adds, “Any underrepresented audience that’s trying to find their voice in mainstream culture through art can relate to that struggle.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.