DMX rapped, and lived, with a ferocity unmatched in the annals of hip-hop

In a November interview with Talib Kweli, rapper DMX was searingly candid about his drug use and the trauma that drove it. “I learned that I had to deal with the things that hurt me,” he said. “I didn’t really have anybody to talk to … talking about your problems is viewed as a sign of weakness when actually it’s one of the bravest things you can do. One of the bravest things you can do is put it on the table, chop it up, and just let it out.”

He recounted how, as a 14-year-old, he’d unwittingly smoked a crack-infused blunt, which introduced him to drugs and began a stormy, lifelong relationship with self-medication to heal his pain. “Drugs were never a problem, drugs were a symptom of a bigger problem,” he said. “There were things I went through in my childhood where I just blocked it out. You never know when the things you stored away are going to come out and just fall all over the place.”

The interview seemed an encouraging sign that the rapper, born Earl Simmons, was finally rounding a bend on his difficulties with substance abuse, after canceling a tour and checking into rehab in 2019. But the 50-year-old rapper succumbed to that longtime struggle. DMX died on Friday after suffering a heart attack on April 2, following an overdose at his home in White Plains, N.Y.

Born Earl Simmons, the New York-based rapper and actor was hospitalized after having a heart attack following a drug overdose.

A statement from his family read, in part: “We are deeply saddened to announce today that our loved one, DMX, birth name of Earl Simmons, passed away at 50-years-old at White Plains Hospital with his family by his side after being placed on life support for the past few days. Earl was a warrior who fought till the very end. He loved his family with all of his heart and we cherish the times we spent with him. Earl’s music inspired countless fans across the world and his iconic legacy will live on forever.”

DMX’s life and career were contradictions from the start. He was devoutly religious yet accrued a lengthy list of arrests and incarcerations — most recently, in 2018, he went to prison for tax fraud. He possessed one of rap’s most distinctive, combative vocal tones, with gut-spilling lyrics churning through his difficult youth in 1980s New York, yet he was also a staggeringly popular artist, topping the Billboard 200 with each of his first five albums, starting with 1998’s landmark “It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot” on Ruff Ryders/Def Jam. All told, he had 15 Hot 100 singles. He also was a charismatic film star in critical and commercial successes like “Belly” and “Romeo Must Die.”

Rapper DMX has died at age 50 after suffering a heart attack. Halle Berry, Chance the Rapper and Viola Davis are among celebs paying their respects.

From the opening salvo of his first major-label single, “Get at Me Dog,” to “Stop Being Greedy” and “Ruff Ryders Anthem,” the ultimate get-ready-to-rumble rap track that helped made producer Swizz Beats’ career, DMX possessed a voice like no other. His delivery was deep, frantic and hoarse, yet with a coiled intensity that made his songs feel like hits even as he rapped: ’N— wonder why N— wanna die / All I know is pain, all I feel is rain / How can I maintain with that s— on my brain?”

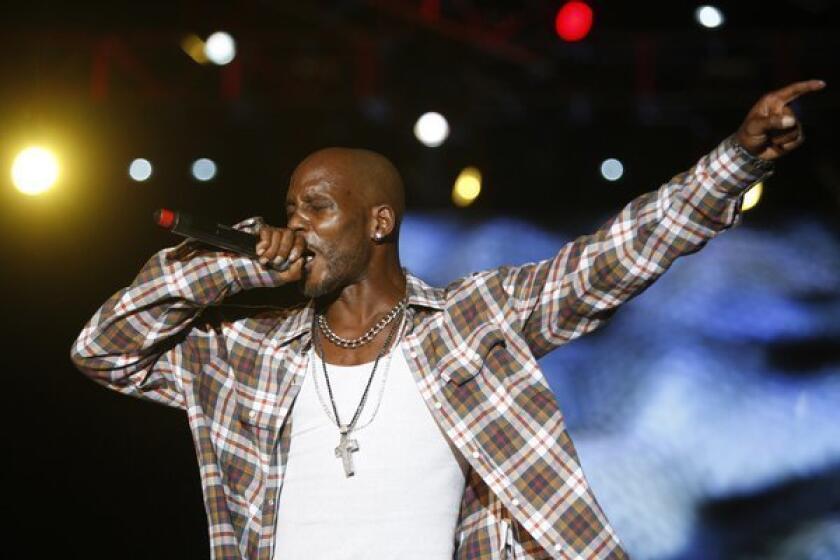

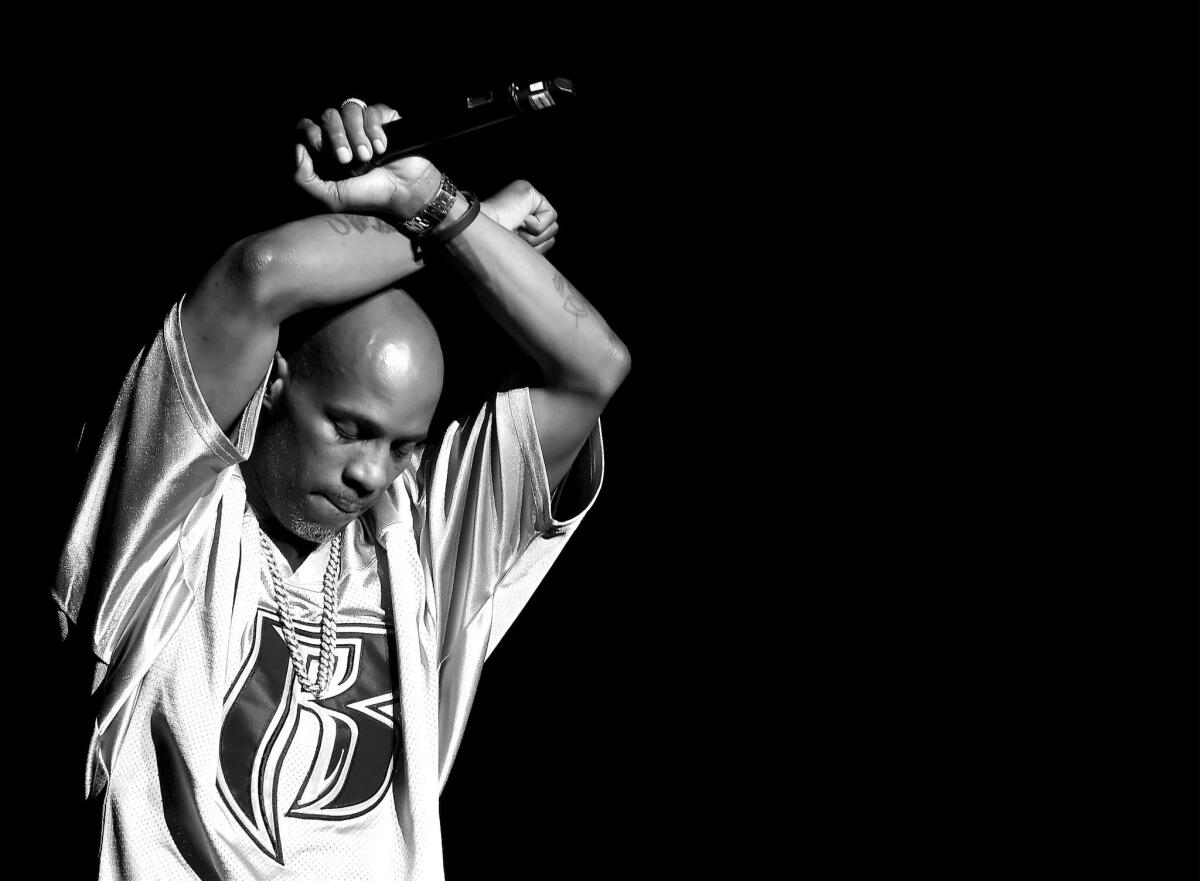

DMX would prowl the stage with tendons rippling, eyes aflame, a physical manifestation of the storms in his head. But he hit more ruminative and tender notes as well, as on “How It’s Goin’ Down” with R&B singer Faith Evans. “It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot” was an instant classic, and it made him an immediate but troubled superstar.

With his follow-up later in 1998, “Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood,” DMX was already wrestling with the demons of drug abuse. “Slippin” used a Grover Washington Jr. sample to moving effect, while DMX laid out how a childhood laced with uncaring institutions, absent family and drug use bent his sense of self. “Group homes and institutions prepared my ass for jail,” he rapped. “Used to get high, just to get by / Ate somethin’, a couple of forties made me hate somethin’ / I did some coke, now I’m ready to take somethin’… I’m possessed by the darker side, livin the cruddy life / s— like this kept a N— with a bloody knife.”

His third album, 1999’s “… And Then There Was X,” was a juggernaut on the charts, going six times platinum on the strength of “Party Up (Up in Here),” which retooled his tense paranoia into a monster hit that would echo at clubs and sports arenas for years to come. “What’s My Name” and “What These Bitches Want” took a darker, tenser flip on that template, but now, DMX wasn’t just a growling, compellingly paranoid entry to the New York canon — he was a superstar.

He also defined a transitional era in hip-hop, as it moved from the bicoastal wars and gang conflicts of the late Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur into a new, dominant form of popular music. After Biggie, Jay-Z may have become the King of New York, and Wu-Tang Clan made the city a mythic realm. But DMX was New York rap at its most distilled: brash deliveries, a hard-bitten worldview and productions rooted in soulful, confident horn samples. His sprawling Ruff Ryders crew (alongside future stars Eve, Ja Rule and in-house producer Swizz Beatz) kept hits coming from all directions.

The next albums of his Billboard 200 streak lost a little of that momentum, even with occasional standout singles like 2001’s “Who We Be” that drew lines among the societal failures of prison, drugs and isolation that broke Black communities (its video, with black-and-white protest footage from the ‘60s, felt like an antecedent to Lil Baby’s “The Bigger Picture” clip).

2003’s “X Gon’ Give It to Ya,” a bigger-than-life anthem from the soundtrack of the action movie “Cradle 2 the Grave,” became his final signature hit, eventually serving as mixed martial arts walk-out music, the backdrop for a killing spree in the 2016 film “Deadpool” and as the musical bed for a “Rick and Morty” montage that became an ever-present reaction meme. In 2016, Bernie Sanders even used DMX’s “Where the Hood At?” as walk-on music to a rally in Lancaster, sending rap fans and leftists alike into unlikely glee.

While DMX had devoted much of his late career to preaching in his Christian faith, he’d reportedly re-signed with Def Jam. In an era with so much nostalgia for the era of rap and pop he helped epitomize, this could have been the beginning of a much-deserved comeback. So many young rappers have fallen victim to drugs and violence of late; it’s only compounding to watch older ones struggle so deeply with the same things.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.