L.A. nightclubs exhale as stimulus money and even an end to shutdown appear in sight

Seven years ago, Candice Fox caught a show at the Hotel Cafe, a tiny singer-songwriter venue in Hollywood. Local singer Javier Dunn was on the bill that night, and Fox was smitten. “I emailed him the next day to go for a drink, and we’ve been together ever since,” Fox said. She later got a job bartending at the venue, where she still works. “We always joke that we’re going to get married there,” Fox said.

That’s assuming the Hotel Cafe can stay open.

On Grammy night, the 30-year-old Fox presented Taylor Swift with her prize for album of the year, as part of a Grammy campaign to highlight struggling, pandemic-shuttered music venues across America (other presenters included staff from the Troubadour, the Apollo in New York and Nashville’s Station Inn).

It was a huge moment for the beloved venue, which hosted early-career gigs from Adele, Ed Sheeran and Katy Perry.

Like all venues in L.A., it’s been closed since March of 2020, and the bills have piled up, even as specific relief for music venues passed in December’s COVID-19 relief bill. Many venue operators wondered when those funds from the Save Our Stages Act were actually going to start saving stages.

“It would be the cruelest irony,” Fox said, if “the money didn’t come through at the final moments before the finish line.”

Now help could actually be on the way. The Small Business Administration, the federal agency tasked with distributing $16 billion for music and cultural venues (now dubbed the Shuttered Venue Operators Grant), announced on March 19 that it would open up for applications on April 8.

The move will bring some clarity — and hope — for one of the more devastated industries in the pandemic.

“These grants would give us life,” said Gia Hughes, production manager at the Hotel Cafe. ”Without it, venues will close. Our debt will continue to be insane, if we want to stay open on the other end of this. These grants everyone is waiting on will make or break music in America.”

Forced to shut down because of the pandemic, Amoeba Music plans to open in its new Hollywood Boulevard location on April 1.

As the county and state plan for reopenings, the signs look hopeful. In L.A. County, cases are down more than 60% from just two weeks ago. Over 25% of Californians have received at least one dose of a vaccine. L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti recently estimated that half to two-thirds of L.A. County residents had antibodies against COVID-19, either from infection or vaccination. The county, currently in the red tier — the second-most-restrictive category in the state’s color-coded reopening plan — could soon move into the less restrictive orange tier, which would allow for bars to serve outdoors and increased capacity at movie theaters, restaurants and other venues. In the yellow tier, outdoor concerts with reduced capacity and restrictions could return as well.

But indoor music venues won’t be able to reopen in California until the county clears all of those tiered restrictions. Even afterward, it will likely take weeks to months for anything like normal touring to resume. To survive until then, many venues say they desperately need government support.

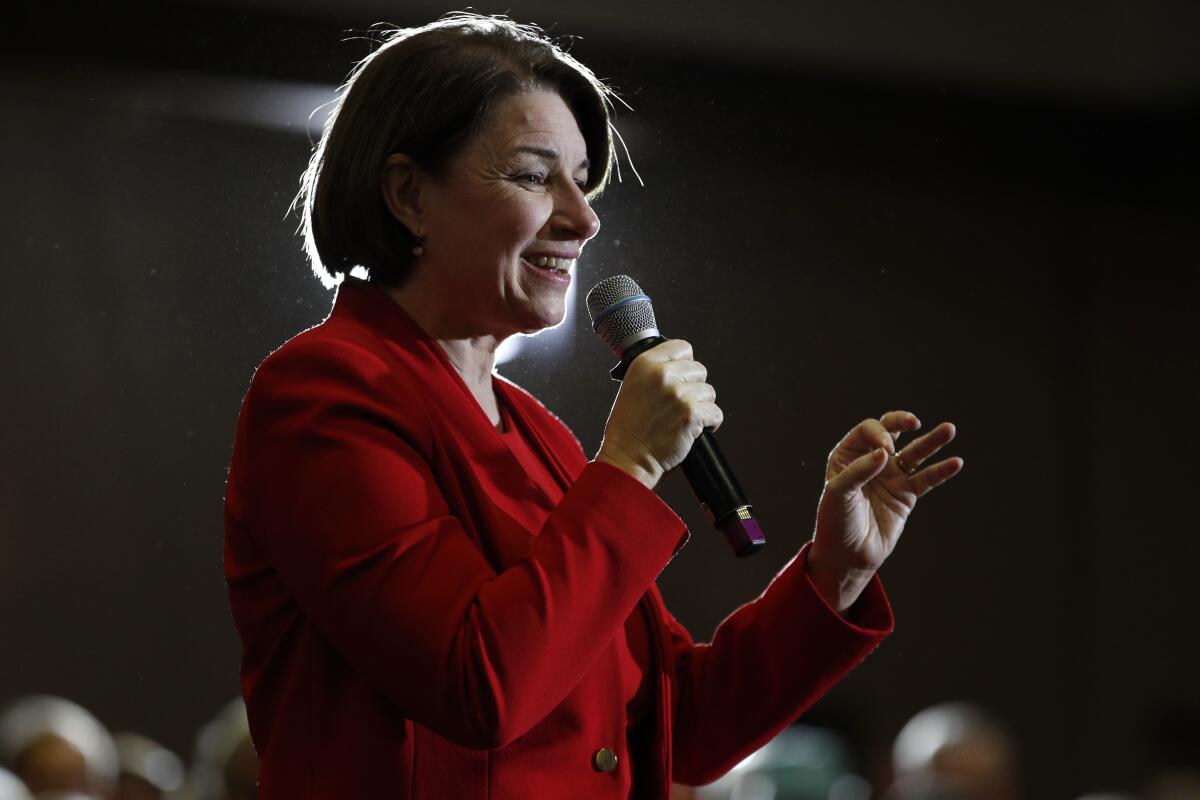

After a year of relentless grassroots organizing and lobbying by the National Independent Venues Assn., the industry scored a huge victory in the face of an existential crisis for live music. Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and John Cornyn (R-Texas) championed the Save Our Stages Act, with support from now-Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.). They worked its provisions into a massive end-of-year government funding bill signed by then-President Trump.

Venue owners, staff and bands rejoiced. The grants would be good for 45% of their 2019 gross earned revenue or $10 million (whichever was less). Maybe their favorite spot would still be there after the coronavirus subsided, and touring would still be viable for artists eventually.

But as the weeks rolled on — through the Capitol insurrection, President Biden’s inauguration, Trump’s second impeachment and the passage of the $1.9-trillion American Rescue Plan — venue staff started wondering when, exactly, those checks would be arriving.

“When that bill passed, it was such a sigh of relief,” said Audrey Fix Schaefer, spokesperson for NIVA. “Venues could show news articles about it to their landlords and say, ‘I’ll be getting this money, I can pay rent.’ Then months went by. I’m hearing more and more stories about drained savings, drained 401(k)s, drained college funds. Until that money hits, venues aren’t saved.”

“It was a miracle that NIVA was able to get this passed,” Hughes agreed. “But if you want to see music again, venues need the feds to release those funds immediately.”

Multiple women accuse owners of the Cloak & Dagger nightclub of sexual misconduct and of overlooking misconduct by famous members.

There are several reasons that those grants for venue operators took longer to get moving than might have been hoped, said U.S. Rep. Judy Chu, whose congressional district includes much of the San Gabriel Valley. Chu serves on the the House Small Business Committee, which oversees the SBA.

“The SBA has never operated a grant program like this. It’s had to build a completely new system for grant dispersal,” Chu said. “We saw what happened with the Paycheck Protection Program when it was first rolled out — big businesses dominated the applications. There are always pains in starting a new program.”

The logistics are indeed complex, as the SBA has had to get a national application system in place and must verify which music and arts venues can qualify. Venues will be placed in line according to the level of income they’ve lost. Meanwhile, the American Rescue Plan allowed venues to take a second dip into PPP money to pay salaries while awaiting these grants — which can be used for various expenses including rent, utilities and inventory — to come through.

Although low-capacity reopenings might help restaurants and retail stores, music venues can’t profitably put on shows with a fraction of the usual crowd. “When we have vaccines in everyone’s arms, that is when the industry can reopen fully,” Schaefer said. “Venues are built on national tours, and I don’t know who a 30% capacity show will help. The only thing worse than being shuttered is being partially open.”

For months, venue staff wondered when those federal checks would come. An already cruel year would be compounded if they had to close right before checks started going out the door.

But that seems a little less worrisome now that the SBA has announced a start date for applications. The Senate also confirmed a new head of the SBA, Isabella Casillas Guzman, a former Obama SBA official and director of California’s Office of the Small Business Advocate, whom Chu says “really understands this situation.”

Though no exact date is set for when venues can expect to see the funds arrive in their bank accounts (a process that will likely take weeks, at least), Chu hopes that venues can now plan for the future with greater assurance.

“I know how much they’re suffering, and we cannot delay this effort,” she said. “The Troubadour contacted me, and the thought of it shutting down and being gone forever, I felt we had to do something to save it. It shows that the voices of those who work in live venues had an impact, and people listened.”

In the meantime, small venues such as the Hotel Cafe have racked up debt, staff are laid-off or furloughed, and bands are waiting for the virus to subside enough to allow for shows. That time might be months away, but the SBA’s grants may ensure that stages are still open.

“The venue is a second home in L.A. to me,” Fox said. “All the people I work with, I deeply love and care for them, they feel like part of my family too. I can’t imagine my life in L.A. without this venue being open. But we’re all starting to see a light after a very dark, scary tunnel full of uncertainty.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.