Brian Eno has had a pretty good quarantine

Like you and me, Brian Eno has spent way too much time on Zoom lately. But unlike us, he’s taking steps to create a better solution to group video communication.

“I’m working on a project with some Dutch friends to make the next generation of this kind of communication,” he says during a (what else?) Zoom call. “We’ve come up with some interesting ideas for an etiquette of how it works — a new set of assumptions, really. We’re hoping to launch it next summer as an open source thing where it’s available for anybody to improve it for us.”

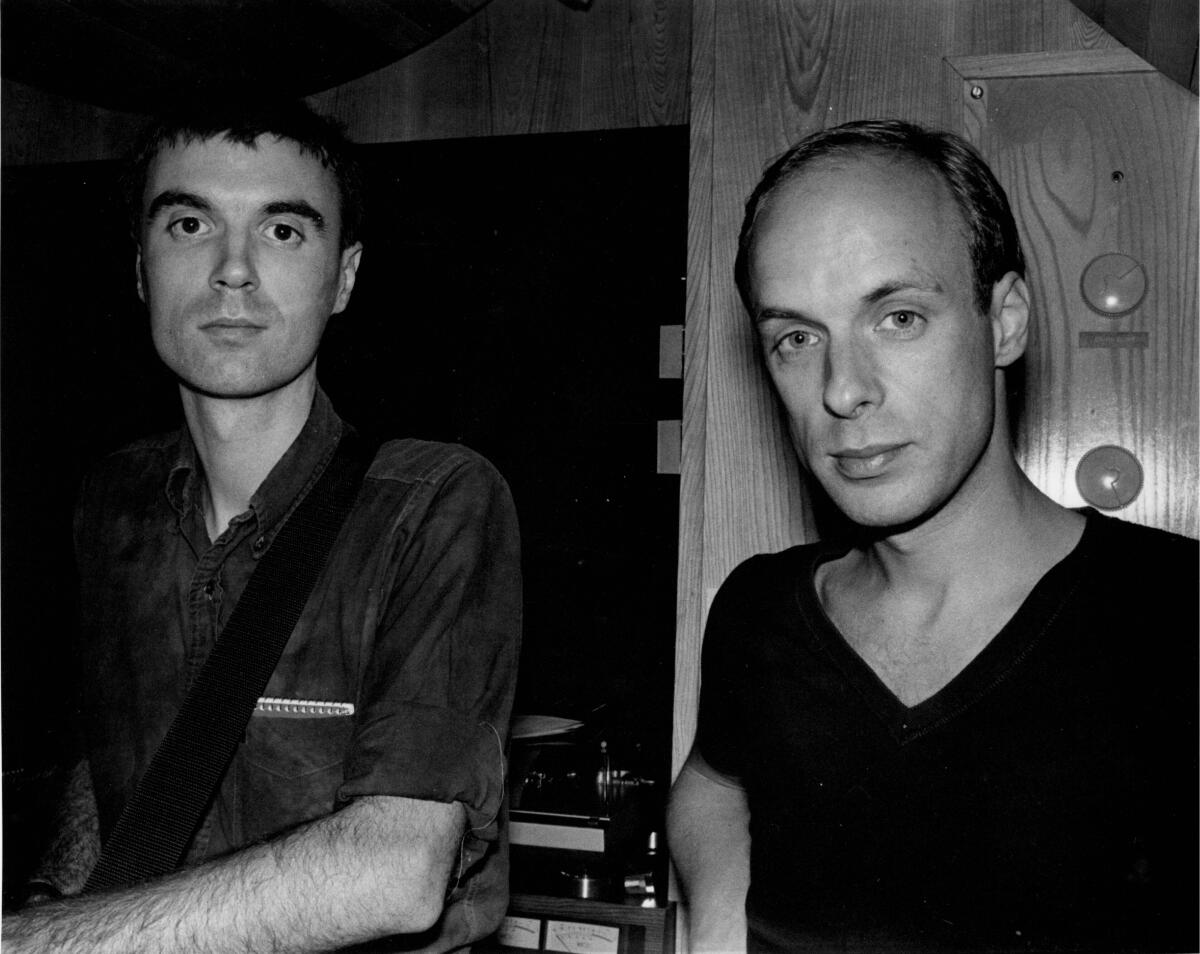

For a little more than 50 years, interesting ideas and new sets of assumptions have been Eno’s firmament. A charter member of the great U.K. band Roxy Music, he’s also a solo artist who has moved between funk and ambient music (which he named), and a producer whose catalog, ranging from Talking Heads to U2, from David Bowie to the Portsmouth Sinfonia, is unmatched.

If that weren’t enough, he’s a visual artist (his light boxes, with LED lights that change slowly and randomly, typically sell for just south of $50,000), an unconventional film composer and the only member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame who could rightly be called a public intellectual.

Eno, who is 72, grew up in the conservative harbor town of Woodbridge, England, in the rural county of East Anglia, the son of a British postman who fixed watches in his spare time and a Belgian mother who’d spent World War II in a German labor camp. Eno blossomed at art school — first Ipswich and then Winchester — growing out his hair, wearing makeup and ingesting colorful Pop art theories he applied to synthesizer and tape-recorder experiments.

Last year, he and his younger brother Roger Eno, a keyboardist, released their first album together, “Mixing Colours,” a pacific, echoing ambient set which is the inspiration for an audio-video installation, “A Quiet Scene,” presented in the Los Angeles Music Center’s Jerry Moss Plaza from Jan. 22 to Feb. 21. And on Friday, Eno released his original soundtrack to “Rams,” a documentary about the German industrial designer Dieter Rams, as well as “Film Music 1976-2020,” which compiles music that appeared in “Dune,” “Heat” and “Trainspotting,” among the better-known films, and three additional EPs of film music.

A tiny credit on John Cale’s 1974 album “Fear,” which Eno played on, helps clarify Eno’s position in music. Cale credited various people with playing different instruments — “Drums: Fred Smith,” for instance. Eno’s credit just says “Eno: Eno.” He is an N of one.

Talking from a home in Norfolk, England (“a quiet little village” about 100 miles northeast of London), where he relocated once the pandemic started, Eno talked keenly and hilariously for an hour about his memories of David Bowie, the phone app that rekindled his interest in music and how he’ll release music after he’s dead.

Most music doesn’t have a utilitarian purpose. One exception is dance music, which is supposed to make you dance, and another is ambient music, which is meant to fade into the background. Is there a purpose to film music?

There are lots of different ideas about what film music should do. The Scandinavian Dogme 95 movement said there should never be music added to a film — if you want music, you generate it within the context of the film. So if you want music in a love scene, somebody has to put the radio on or put a record on. There’ve been some very notable successes in that, particularly [the 2018 Icelandic movie] “Woman at War,” which is so great. In that film, whenever music is needed, there’s a band playing within the scene, even if the scene is in a lava field in the middle of Iceland, which it often is [laughs], and there’s something so curious and interesting about that.

The other extreme is the sort of John Williams wall-to-wall music. Films like “Star Wars” are orchestrated from beginning to end, I think. I’m of neither of these persuasions myself. I want to increase the richness and the ambiguity of a scene. It’s the opposite of what a lot of film composers are doing, which is trying to reinforce emotions that are already intrinsic to the scene. If it’s sad, out come the tinkly pianos and violins. And if it’s thrilling, out comes the big brass orchestra and fast drums. I like music to be almost a counterpoint to the action, so it’s as though there’s a halo of other possibilities around it.

Movies have a hierarchy of importance, don’t they? The music is usually there only to enhance a picture, which implies they’re not equals.

I think that’s one of the things that first attracted me to film music. Fellini films were very popular among art students in the ’60s. I became aware that music was a big part of what I liked about them. So I bought the soundtrack of “Juliet of the Spirits” and I absolutely loved it. It was music with something missing, in the sense that music was the frame to the action. But when you took the action away, it left an inviting spaciousness that you could then enter. I used to put the television on, turn down the sound, and play the “Juliet of the Spirits” soundtrack along with what was on TV. [laughs] It made everything more interesting, actually!

I was quite sick of music that was overstuffed. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, recording went from two track to four track to eight track to 16 track to 32 track, and music got more and more grandiose, sometimes with good effect, but quite often not. These [Fellini] film soundtracks were spare and light and thin, in an ethereal way. This was in the early days of thinking about ambient music — music that is deliberately, as you said, functional, and isn’t saying, “Sit in a chair and concentrate because I’m going to show you something amazing.”

Ambient music, which you began making in 1975, to the confusion of many who loved what you called your “idiot energy” rock albums, has become invaluable recently to people with anxiety and insomnia. I’ve been listening to your ambient records a lot lately — specifically the past four years.

You’re right, this has been a time that demanded a different kind of music — a different kind of listening. Because most of us have been confined, we’ve been looking for space — psychological space, really.

I’ve always used music to create the space I wasn’t finding in my life. When I lived in New York on a very busy intersection in the early ’80s, where the traffic noise was loud, I started making very spacious, empty music. I made “On Land,” which doesn’t sound like music — it sounds like a world, if you like. I moved back to England, to rural England, and I started making really noisy music, like “Nerve Net” or “My Squelchy Life.” [laughs] It sounded just like New York!

I rediscovered my enthusiasm and passion for music lately by listening to an app called Radio Garden. [Radio Garden has a world map with clickable links to streaming stations in every country.] My favorite station, which is called Orthodox Chants, plays chants 24 hours a day from Cheboksary in central Russia; one spacious, moving chant into the next. I found another station in northern Madagascar, Alefamusic, which has the most unusually complex Afro-Arabic music. It has the rhythmic complexity of African music, but exaggerated, so they’re always working with both a four beat and a three beat at the same time. My daughter is about to have a child and I persuaded her that she should play this station to her tummy. The music reminds you that there are always at least two worlds going on at the same time.

Speaking of daughters, next month Faber Books is reprinting “A Year (With Swollen Appendices),” which includes a diary you kept in 1995, plus essays and other writing. There are some very sentimental entries about your younger daughters, who were 3½ and almost 5 when you started the diary. Do you think that sentimentality is evident in your music?

I think my work is quite sentimental sometimes. My brother and I have a name for the kind of music we do, we call it East Anglian Miserablism. [laughs] In this part of England, there’s a tradition of — not really misery, but melancholy. A lot of the art that comes from here has both a joy of being alive and a sense of regret of what’s always being lost.

The new edition adds a few short stories you wrote, which are unified by what I’d admiringly call a perverse sexuality.

Yes!

Your first few rock albums had that same quality. What happened to that kinky content?

It was always to do with the lyrics and the sense that there was a kind of smutty English adventure going on. That left my music when I stopped writing lyrics. Which is not to say it won’t come back. I recently started writing songs again, and the one I was working on today does have a rather smut section in it. It would be embarrassing if that theme reappears when I’m 83 — when you can only talk about it, not do it.

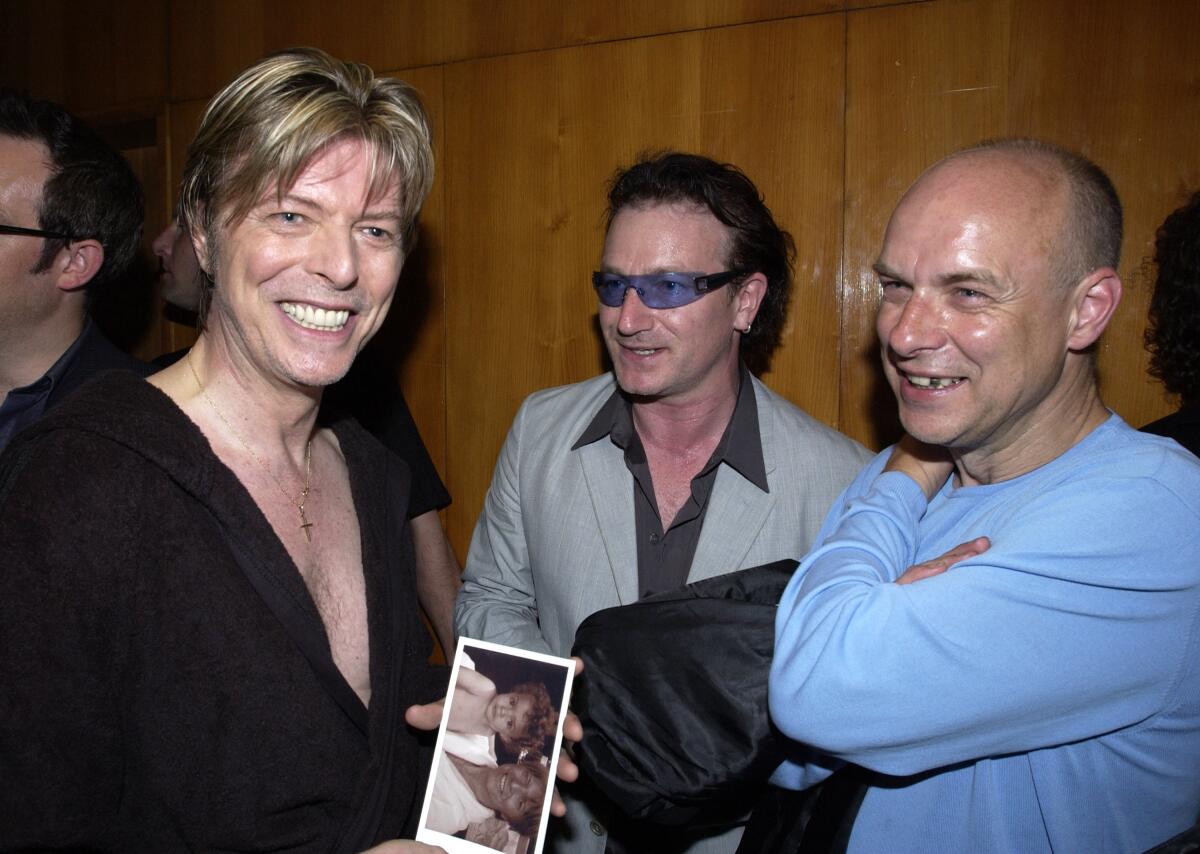

You made a lot of music with David Bowie and co-wrote “Heroes” with him. What did you and he have in common?

We shared the same sense of humor. Like a lot of good singers, he was a brilliant mimic. The first day we worked together, he said, “I wrote a song for Bob Dylan. It sounds pretty good.” He played the song on the recording studio monitors and I was thinking, wow, this is great — Dylan is back on form. I became aware of David laughing in the back of the room. And it was of course him singing, not Dylan.

Another thing that’s quite interesting was watching him record a vocal. You could tell he was figuring out [the personality of] the character who was singing. He would tune the character. It makes sense to think of him as an actor who’s designing his own plays. I remember him saying once, after a take, “Was that a bit too lumberjack?” [laughs]

Do you look forward to getting back into the studio with a band as a return to normal life?

I haven’t missed it, to be honest. I’ve done a couple of pieces with bands in other countries, working on their stuff and sending it back. In nine months, I’ve only left this village three times. I found the emptiness quite refreshing. I’ve enjoyed the silence.

There’s one other thing I’ve enjoyed as well. I’ve been doing a lot of Zooming and having conversations with five or six people — scientists, artists, politicians — who otherwise would never get together because they’re geographically so far away from each other. Sometimes I think, blimey, I’m talking to Yanis Varoufakis [Greek economics professor], Kate Raworth [British economist who studies environmental issues] and Mariana Mazzucato [British economics professor] and I haven’t left my living room. I think the quality of interaction among intellectuals has really shot up.

You have several thousand unreleased pieces of music stored on various media. To ask a macabre question, what happens to that music when you die?

In fact, I was talking about this with somebody today. There are a lot of pieces. A lot of it is not very good. I hope those pieces will die with me. [laughs] But some of it is good. I was having a discussion about the idea of a permanent, accessible archive, like a radio station that only has my music on it. That would be a nice way of having an archive. You just leave it to the world, to do with it whatever they want. It’s mostly half-finished material.

Either way, once you die, it’s finished.

That’s what you call a deadline. [laughs]

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.