Nowadays, disco and the Bee Gees are widely beloved. But that sure wasn’t the case 40 years ago

Any retelling of the 1970s disco boom has to reckon with Disco Demolition Night, a shameful promotional event staged by Chicago shock-jock DJ Steve Dahl between games of a White Sox doubleheader on July 12, 1979. This violent debacle is a convenient summary of the backlash disco faced, and is often cited as the music’s terminus, which it wasn’t.

Disco began as underground music enjoyed in illicit clubs by an allied subculture of gays, women and people of color. In many cases, discos were illegal: In New York, Baltimore, Chicago and L.A., it was against the law for same-sex couples to dance together, and police were often only too happy to enforce it.

As disco became more popular, especially after the late 1977 release of the blockbuster film “Saturday Night Fever” and its soundtrack, which heavily featured the Bee Gees, those quiet subcultures became more visible, pushing feminism, civil rights and gay rights to the lucrative forefront of pop culture. It wasn’t long until Rev. Jerry Falwell was placing disco on a list of scourges that included abortion, and, for some reason lost to time, TV sitcoms.

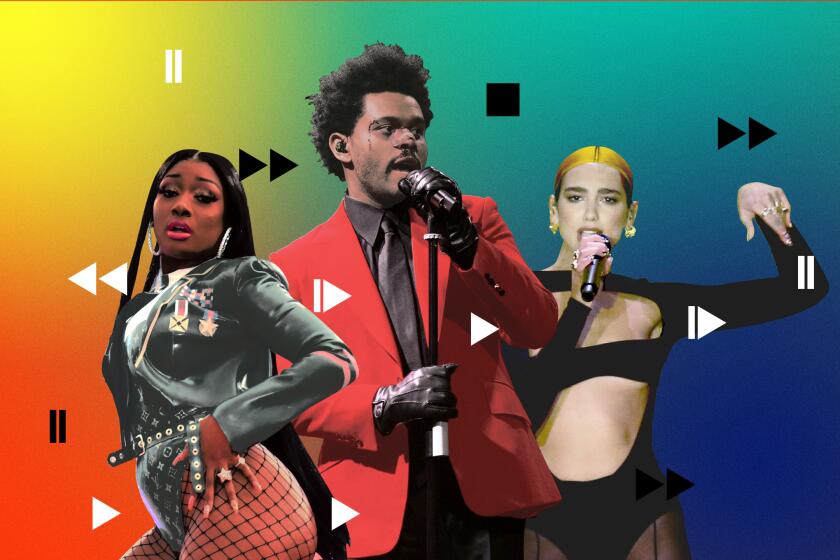

From Fiona Apple to Yves Tumor and a head-spinning assortment of artists and genres in between, these are, alphabetically ordered, our favorite songs of 2020.

Disco added a quarter-note pulse to the meaty basslines and chattering rhythm guitar of funk; Fred Wesley, a key member of James Brown’s band, described disco as “funk with a bow tie.” To skeptics (most of them white and straight), disco was devoid of intelligence, musicality or passion. Once disco became ubiquitous, once morning-radio jock Rick Dees and basketball star Meadowlark Lemon had released disco records, and once moms and aunts were taking hustle classes, these skeptics turned insane.

Soon, macho man Ronald Reagan would run for president on a platform that included race-baiting references to “states’ rights” and fictional “welfare queens”; as president, Reagan would ignore the AIDS crisis until well into his second term. A culture war was coming, during which white Americans would tell marginalized groups to sit down and shut up.

Insane is the only way to characterize the riot that ensued after Dahl blew up disco records in center field at Comiskey Park. “7,000 fans rushed onto the field, starting bonfires, tossing firecrackers into the stands, and destroying turf, batting cages, the pitcher’s mound, and, of course, records,” Alice Echols recounts in her book “Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture.” The White Sox had to cancel the second game of the doubleheader, which they lost by default.

No act was more responsible for disco’s ubiquity than the Bee Gees, a trio of brothers who started their careers imitating the most baroque parts of the Beatles, discovered their magnificent facility with soul ballads, and just as their career seemed spent in the mid-1970s, began making dazzling disco records distinguished by their elastic falsetto voices.

In a five-year period from 1975 to 1979, the Bee Gees had 13 songs in the Top 20, including six consecutive No. 1s, in addition to hits they individually or jointly wrote and/or produced for younger brother Andy Gibb, Samantha Sang, Frankie Valli (for the “Grease” soundtrack), and Yvonne Elliman and Tavares (for the “Saturday Night Fever” soundtrack, which soon became the bestselling album in U.S. history). Except for the Beatles, no group had ever been bigger in the U.S. than the Bee Gees were.

In “The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart,” an HBO documentary that premieres Saturday, oldest brother Barry Gibb makes it clear that Dahl’s stunt helped persuade the Bee Gees to shutter their own band and focus instead on writing and producing for other artists. The surprisingly poignant documentary, directed by Frank Marshall, uses old interviews with Robin and Maurice (pronounced Morris) Gibb, who died in 2012 and 2003 respectively, and recent interviews with Barry, who adds a stirring comment to its conclusion; having hits was great, he says forlornly, but “I’d rather have [my brothers] back here and no hits at all.”

It’s left to one of the film’s talking heads, Vince Lawrence, to put Disco Demolition Night into a modern context. Lawrence, an African American producer whose work was integral to the growth of Chicago house music in the late 1980s, and who was working as an usher at Comiskey Park that night, points out that many of the records Dahl detonated weren’t disco — they were R&B records by Black artists. Lawrence calls it “the end of an era,” which isn’t precisely true, but he describes the event accurately and with deserved disgust: “It was a book-burning. It was a racist, homophobic book-burning.”

“How Can You Mend a Broken Heart” includes lots of video of the Bee Gees in the late 1970s, and it’s easy to see why they (and disco in general) triggered homophobes: the brothers, who were straight, had long, carefully-coiffed hair, and wore tight white pants and open blouses. They looked like Cheryl Tiegs and they sang in falsetto. These uncastrated castrati drove straight women mad (especially Barry) and drove straight men crazy. When Steve Dahl used the word disco, he pronounced it with a contemptuous lisp. Men singing in a female range has inspired loathing since the beginnings of rock; Little Richard’s fireball falsetto was one of the biggest reasons the pro-segregation North Alabama White Citizens Council called rock ’n’ roll “unmoralistic.”

There will never be an end to the panic androgyny incites — just last month, Ben Shapiro and Candace Owens freaked out on Twitter at photos of singer Harry Styles wearing a dress for a Vogue cover — but it’s now more readily recognized as a form of homophobia than it was in 1979. The heightened visibility of non-gender-conforming people has prompted a backlash that repeats the sit-down-and-shut-up message of the 1980s. Nostalgia often neuters pop culture — “YMCA,” a song about gay men looking for casual sex, is played regularly at football games — so it’s important to recall that, by virtue of being more popular, disco was more transgressive than its contemporaneous alternative, punk rock.

Disco never died. In fact, it barely paused. Many of the earliest rap records interpolated disco songs, including the Sugarhill Gang’s 1979 landmark “Rapper’s Delight,” which made a meal out of Chic’s “Good Times.” Madonna’s first single was in October 1982, around the same time George Michael (who bit the Bee Gees’ sound and hairstyles) first popped up. Rock bands including Duran Duran, Queen and INXS integrated it into their music. A vanguard of last decade’s bands — LCD Soundsystem, the Killers, Phoenix, Daft Punk — used elements of disco. And recently, there’s been a disco resurgence on the charts, with Dua Lipa’s “Don’t Start Now” (which peaked at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100), Lady Gaga’s “Stupid Love,” Doja Cat’s “Say So,” Harry Styles’ “Adore You,” Lizzo’s “Juice” and the SZA/Justin Timberlake collaboration “The Other Side.”

Ian Kirkpatrick, who produced and co-wrote “Don’t Start Now,” says he didn’t think the song was commercially savvy when he began working on it in January 2019. Radio was dominated by Drake and Billie Eilish, and “nothing was very uptempo at the time,” says Kirkpatrick. “I loved the song, but I wondered, are people gonna appreciate a disco-y song? Turns out the zeitgeist was ripe for it.”

Kirkpatrick, who’s 38 and says he’s “in love with the Bee Gees,” theorizes that the resurgence is partly due to websites like Splice.com, where anyone can, for a cheap monthly fee, download “sample packs” of loops and plug-ins for use on home-recording software. Two of Splice’s top downloaded sample packs are by Oliver (the professional mononym of producer Vaughn Oliver), whose style Kirkpatrick describes as “kind of disco-esque.” The original “Don’t Start Now” track even began with a loop of Oliver’s drums, he says. “The Bee Gees had to learn their instruments and become master songwriters,” Kirkpatrick adds with a boisterous laugh, “and us douchebags just go to Splice.com and download a loop. The barrier to entry of being a producer is much lower these days.”

The zeitgeist Kirkpatrick refers to is straightforward: Hard times call for ebullient music. It was true in the late 1970s, when the economy was failing, and it’s true now when people sometimes haven’t seen family members for a full year. Many of us are more isolated than we’ve ever been before, and celebratory music helps us recall the thrill of being in a club, on a packed dance floor. It’s ironic that disco, which was criticized for sounding mechanical, now functions as a warm, human antidote to precise, quantized songs made on home computers.

It’s no insult to say that none of these current disco-influenced hits equals the melodic, rhythmic and harmonic richness of the music the brothers Gibb started making in 1975 when, on the advice of label mate Eric Clapton, they moved to Miami. The city had a plethora of ace funk session musicians, but the Bee Gees augmented their instrumental skills with a small band of guitarist Alan Kendall, drummer and pocket specialist Dennis Bryon and keyboardist Blue Weaver. Even some of the band’s most devoted fans don’t realize that Maurice Gibb was the band’s bass player, live and in the studio; his basslines on “Night Fever,” “More Than a Woman” and especially “You Should Be Dancing” are as dynamic as anything in pop music.

The Gibbs had been performing together since 1958, after the family moved from England to Australia; Barry was 12 and the twins were 9. Like the Jacksons, they grew up in show business and were managed by their ambitious father. By the time they reached Miami, they were writing songs that had the wings of heaven on their shoes.

Musicians who’ve been vindicated by time sometimes find a satisfaction in old age that was missing in their prime. But throughout “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart,” Barry Gibb — now Sir Barry Gibb — appears to be a bit shell-shocked. He’s 74 and has outlived his parents and three younger brothers. (Andy Gibb, who had a history of cocaine addiction, died in 1988 at age 30 of heart disease.) Barry has an older sister, Lesley Evans, who isn’t mentioned in the film and is little-known to fans.

It’s impossible to not share a little of Barry Gibb’s sorrow at the end of “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart.” But at the same time, it is wonderful to hear those brazen, excited disco classics — to savor, for that matter, that “disco classics” is a genuine category — and to see 20,000 people attending a concert without any fears of a virus. For a long time, the 1970s have been viewed simplistically as a horrible decade for American culture. Forty years after people prematurely declared the death of disco, the music feels remarkably alive.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.