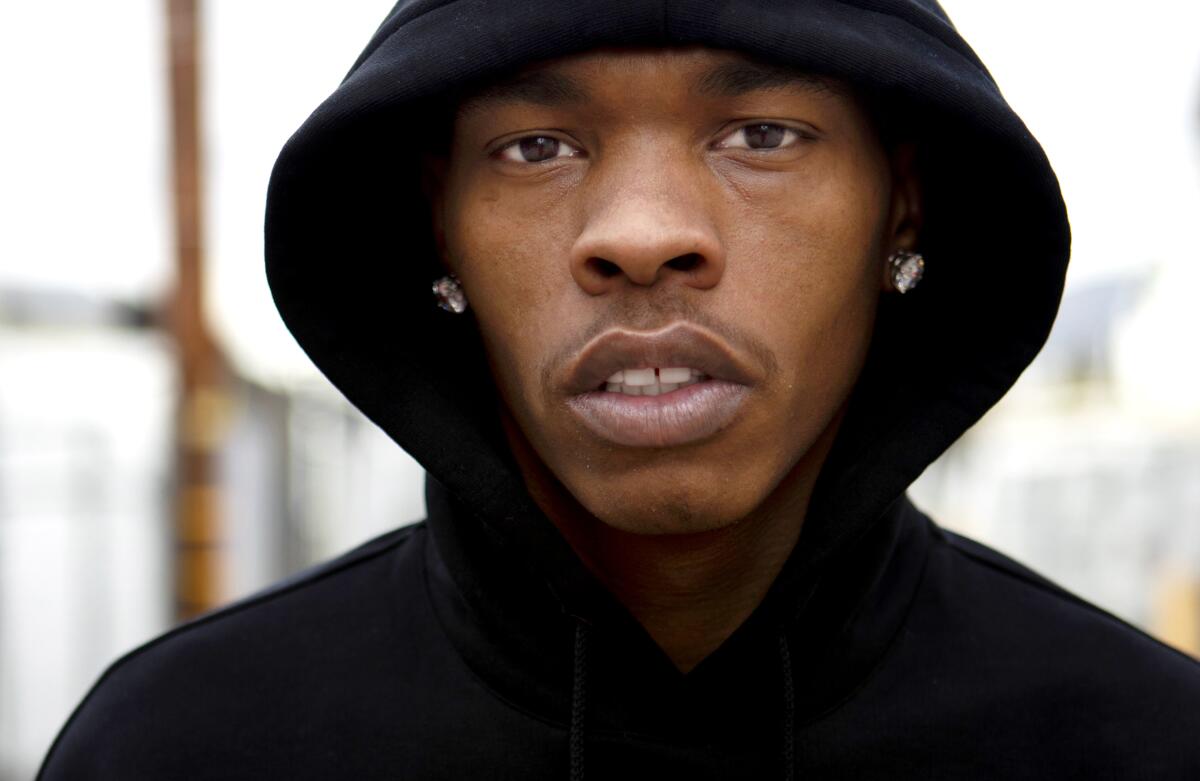

Lil Baby owned 2020. Wait until you hear about his 2021

If you want to talk with Lil Baby in the pandemic-darkened winter of 2020, you have to go through some formidable security.

Outside a recording studio on the southern edge of Hollywood, in the alley of a windowless concrete bunker of a building, a security guard in a black suit and earpiece first took a Times writer’s temperature behind a floor-to-ceiling wall of plexiglass. Guests signed a thick waiver stating that they haven’t had any COVID-19 symptoms, freeing the studio from liability if they catch the virus inside.

Hands were sanitized, masks proffered and an assistant briskly dragged newcomers through a hallway and parked them in an all-white, furniture-less room where a HEPA air filter hummed at full speed. Members of Baby’s team nervously flitted from room to room — a manager, a designer, a few reps working with the rapper’s Quality Control label (the firm that helped break Migos and City Girls). It felt like entering a laboratory working on something dangerous, or maybe a Scandinavian jail.

Producer-songwriter Benny Blanco on his new single with Juice Wrld, the late rapper’s legacy and how the Grammys missed the mark this year.

But once you got through it all, Lil Baby was upbeat. Dressed in all-black Givenchy and intricately barbered braids, the 26-year-old Atlantan born Dominique Jones cracked in disbelief about the Gucci Mane / Young Jeezy battle on Verzuz the night before.

“I was texting a couple of people while we were watching it,” Baby said, recalling the moments where the two long-feuding hometown heroes in Atlanta seemed like they might jump across the stage and strangle one another. “I knew for sure something was gonna go down.”

For 10 months, hip-hop, like every other genre, has been locked out of clubs, tours and festivals because of the pandemic. It’s fared especially well on livestreams and streaming services, though, and Lil Baby is one of the most listened-to artists of this grim year. He’s had a fistful of hits since 2018 chart breakthroughs “Yes Indeed” with Drake and “Drip Too Hard” with Gunna (currently at more than 700 million streams on Spotify) and “My Turn” topped the Billboard 200 album charts in March and then again in June. He’s now clocked 20 billion plays across platforms and counting.

Baby’s hooky, introspective and deeply Southern hip-hop has become a defining sound of the year in lockdown. It’s riff-able enough for TikTok but layered with insight from inside prison and private jets alike.

He’s also up for a pair of Grammy nominations, for rap performance and rap song, each for “The Bigger Picture,” his searingly immediate track that became a protest hit for Atlanta and the world during the uprisings after George Floyd’s killing.

But it’s a weird feeling to be at the top of your career and locked inside like this, with everyone afraid to be together.

“That’s the bittersweet part about it,” Baby said. “I haven’t been able to take it all in, because I haven’t gotten fruits of my labor yet. Hopefully, with the vaccine, stuff will be open next summer. My album’s strong enough to ride it out till the end, though. I almost feel like I got robbed, but I ain’t gonna stop. Everything happens for a reason.”

Baby’s Grammy nominations came for one big reason in particular. “The Bigger Picture” was, in a year of several uncompromising tracks about police and the failed justice system, a standout on its June release, just weeks after Floyd’s killing. “My Turn” and his myriad past mixtapes and records had always documented the tolls of injustice — “Honestly, if you’re a real fan and listen, you know ‘Bigger Picture’ is something I rap about all the time,” he said.

Lil Baby had been immersed in the local scene since Kevin “Coach K” Lee, the chief operating officer of Quality Control, noticed his potential as a 17-year-old selling weed to artists at recording sessions. He’s already clocked two studio albums, six mixtapes, dozens of singles and scads of guest appearances after just four years as a full-time artist.

But “The Bigger Picture” captured something fans new and old needed to hear.

“I find it crazy the police’ll shoot you and know that you dead but still tell you to freeze,” he raps, in a mournful but steadily intensifying cadence. “I seen what I seen, I guess that mean hold him down if he say he can’t breathe.”

“It’s too many mothers that’s grievin’,” he continues, surrounded by protestors in Black Lives Matter shirts in the song’s music video. “They killin’ us for no reason / Been goin’ on for too long to get even / Throw us in cages like dogs and hyenas.”

Baby is fairly neutral about its Grammy prospects. The ambitious “My Turn” didn’t land an album of the year nomination, but “The Bigger Picture” is in strong contention alongside tracks from Roddy Ricch, DaBaby and Megan Thee Stallion, featuring Beyoncé. “Whatever comes, I’ll take it,” Baby said. “If I do win, then I’ll have to go get 10 more Grammys.”

But such acclaim was far from the point when he wrote it. Baby’s a big reader of history and says he can spend hours poring over transcripts or deep-diving on YouTube to soak in old speeches from Malcolm X, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and others during the civil rights era. He saw his generation’s version of that happening in front of him, and he knew he could speak more credibly and more widely than almost anyone from his hometown, a birthplace of the civil rights movement.

“I wanted to be a part of it,” said Baby. “I’d seen it in history books, and now I got the chance to see it firsthand. I knew I was going to be involved.”

Pierre “Pee” Thomas, chief executive of Quality Control, knew right away that the song was much more than just a hit for the fast-ascendant rapper.

“Lil Baby dealt with the feelings pouring out of him the way he knows — he wrote raw and real,” Thomas said in an email. “There have been very few artists in music’s history who can speak a truth that a nation is feeling and help accelerate societal shifts. In his authenticity, and with those words, Baby became one of them.”

Baby also has more personal reasons than many to be hitting the streets demanding reform. In 2016, the rapper finished a two-year prison stint for a spate of gun and drug charges. The experience changed him in ways he’s still reckoning with — in part inspiring his devotion to rap, but also instilling a deep cynicism about how money and connections grease the wheels of justice. He’s one of the most popular rappers on the planet. But in some ways, in both songwriting and life, those prison gates are never that distant.

“If I didn’t go through all that, I wouldn’t be able to speak on it like this,” Baby said. “I’ve got brothers in jail for life without parole. It’s part of my life, and we talk on a daily basis. I’ve got six, seven people with lawyers I retain for them. That’s daily on my brain, so it’s easy to speak on the subject when I get in the booth. I know how they feel.”

The protests galvanized him (the video for “The Bigger Picture” in part used footage of him marching), and as the country’s politics laser in on Georgia’s two Senate runoff elections, Atlanta is once again the center of the world when it comes to the future of civil rights. Lil Baby’s far from naive about the pace of change, but the protests did make him feel it was possible.

“I’m from the bottom,” he said. “Life’s different as Lil Baby, but a President Biden don’t make much of a difference where I come from. People need to see change.”

Lil Baby, perhaps more than any other artist this year, will emerge from the chaos of 2020 as a new superstar, with dizzying streaming figures and regular guest appearances on tracks with the likes of Pop Smoke, DaBaby, Future and Travis Scott. He’s still recording and writing at a fast clip (the week of his 26th birthday, Dec. 3, he released two new singles, “Errbody” and “On Me”), even if the process is a little weirder now than it used to be.

“When I’m in the booth, I usually think about what I’d say to make the club go crazy. Now I’ve got to say it for people at home or on TikTok,” Baby laughed.

But whenever the pandemic subsides, Lil Baby will walk out of his house into a level of stardom he hasn’t seen in person yet.

“I created a different wave since all this,” he said. “I did some of my biggest songs since the pandemic. But I’ve never got to perform them. Once I get onstage, s— be crazy.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.