When Dolly was dark: How Dolly Parton went from bard of death and cruelty to avatar of goodness

A married couple is going to a party. They leave their unhappy children with a babysitter, telling them that they will be up too late to take them to church in the morning. Halfway through the party, however, the husband gets a strange feeling and says they should get home. They are greeted first by sirens and then by flames. The couple makes it to church after all but bearing their children’s tiny coffins. “Though we’d left the party early, we still got home too late.”

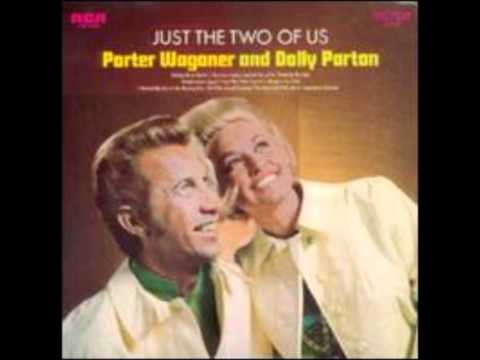

This grim morality tale is “The Party,” the penultimate song on Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton’s 1968 album, “Just the Two of Us.” The photograph on the sleeve, all shiny hair and teeth, gives no indication of the horror in store.

The lyrics appear in “Songteller: My Life in Lyrics,” a new coffee-table book that amplifies some of the dissonant notes in Parton’s work that don’t chime with her 21st century image as an avatar of benevolence and forgiveness, determined to bring together Americans who can agree on nothing else except Dolly Parton. The recent news that she had donated $1 million to Moderna’s coronavirus vaccine research cemented her secular sainthood, extending her mission to make people feel better into the pharmaceutical realm.

But such songs as “The Party” were forgotten long before her canonization. She didn’t crack the Top 10 of the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart until 1970 and only became a crossover star in 1977. There was no pressing incentive for fans of “Jolene” or “9 to 5” to excavate the albums she recorded in her early 20s and uncover the trail of bodies they contained.

“I never shied away from any topic, whether it was suicide or prostitution or women’s rights or whatever,” Parton writes in “Songteller,” but that makes her sound like a protest singer, morally compelled to engage with the issues facing working-class women in the South. It doesn’t explain luridly punitive songs such as “The Party” or “Evening Shade” (1969), in which abused children burn down their correctional facility, killing the matron who has tormented them: “Evening Shade was burning, just like the Hell it was.”

In the book, Parton herself seems surprised by the darkness of her youthful imagination. “Only when I start talking about it or thinking about it do I realize how morbid I really am. People always say, ‘You just seem so happy.’ I say, ‘Yeah, but I can certainly write you a morbid song!’”

This talent was part of her musical inheritance as a daughter of Appalachia. Parton, her parents and her 11 siblings lived in a one-room shack at the foot of the Great Smoky Mountains in eastern Tennessee, without the money for a television or record player, so the first songs she heard were ones that the people around her could sing themselves. She has said that her most important songwriting influence was her maternal aunt, Dorothy Jo Hope, a banjo-playing evangelist who later co-wrote songs such as “Daddy Come and Get Me,” about a woman committed to a mental institution by her cruel and faithless husband.

The Appalachian folk songs that Parton’s mother sang to her were often bloodstained and haunted. Dating back to the British Isles in the 17th century, when entrepreneurial songwriters would sell murder ballads at public hangings, the songs traveled with English and Scottish immigrants to the New World, where tales of old outrages were planted in new soil.

Take “The Bloody Miller,” which described a real-life case of a man killing his pregnant lover in 1683 and eventually mutated into the country standard “Knoxville Girl,” made famous by the Louvin Brothers on their aptly named 1956 album, “Tragic Songs of Life.” Murder ballads were traditionally sung from the perspective of the killer (male) rather than the victim (female), but Parton, once she was established in Nashville, wanted to fill in the gaps and give voice to the mistreated.

There was a public appetite for haunting narratives. Parton launched her solo career in 1967, the year that Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe” entranced America with its cryptic account of the aftermath of a small-town tragedy, but whereas Gentry cannily withheld the details, Parton liked to tell the whole story, right up to the final savage twist.

She was especially moved by the shame attached to unwed mothers in the unforgiving time before Roe vs. Wade. In “The Bridge” (1968), a romantic rendezvous becomes the site of a desperate suicide, and the song comes to a dead stop. In “Down From Dover” (1970), a socially ostracized girl waiting for her feckless lover to come home gives birth to a stillborn baby: “Dyin’ was her way of tellin’ me he wasn’t comin’ down from Dover.” Much is made of Parton’s unstoppable ambition, but she didn’t write songs like this to get on the radio. “The ‘Dover’ tune is very beautiful and well-produced, but the theme is perhaps a little too strong for airplay, even in this day of enlightenment,” Billboard’s critic observed.

Not every Parton song was a bummer. On her first few albums, she sang songs about love and Tennessee and covered recent hits such as “In the Ghetto” and “Harper Valley PTA.” But each time, she would sneak in at least one thorny song about the painful consequences of abuse, like “’Til Death Do Us Part” (1969), in which an abandoned wife keeps her wedding vow with the aid of a bottle of pills, or “Robert” (1970), whose narrator reveals that the rich boy pursuing her is actually her half-brother.

Having been regarded with suspicion by feminists in the 1970s, Parton has always rejected the label by protesting, “I love men.” But she does not love the men in these songs. If they are not outright villains, then they are callous, selfish and oblivious to the pain they have caused. Although these songs weren’t autobiographical (she was already married, and never had children), many were inspired by stories she had heard from family, friends and neighbors. Perhaps you could call them protest songs after all. The subtext is: Listen to me. Don’t run away. Confront what you have done. It’s a country tradition that survives in songs such as Reba McEntire’s “She Thinks His Name Was John” or Martina McBride’s ”Independence Day.”

In the early 1970s, Parton’s canny, domineering mentor Porter Wagoner steered her toward more conventional subject matter, but her songwriting was maturing anyway. It became possible for a Parton narrator to be jilted without being utterly destroyed. “Jolene” may be desperately sad, but it chooses suspense over melodrama, while “I Will Always Love You” is the most gracious breakup song imaginable.

Yet Parton didn’t entirely abandon that earlier mode of storytelling. In 1982, when she was a platinum-hit maker and newly minted movie star, she wrote the damningly bleak “Hollywood Potters” after an extra on “9 to 5,” her debut movie, killed himself. The following year, she released “A Gamble Either Way,” about a teenage orphan who has been so relentlessly exploited by men that her idea of a happy ending is to join a brothel: “I was good at pleasing strangers, so I made the most of it.” That one was based on a distant cousin who became an escort. Even as Parton’s own story traced a classic rags-to-riches arc, empathy drew her to the tough choices that arise from brutally circumscribed lives. There but for the grace of God, perhaps.

Such songs do not, of course, figure in Parton’s set lists these days. Whereas Johnny Cash’s latter-day reputation depended on him leaning into the darkness, Parton’s sassy, sunny persona chases the shadows away. She is concluding this difficult year by releasing a festive album, “A Holly Dolly Christmas,” and an accompanying Netflix special. Her shows are carnivals of good-natured inclusivity that unite everyone from LGBTQ millennials to MAGA-hat boomers under one roof. There is room for heartbreak but not deep cuts about suicide and arson.

Still, she would not have included so many of these dramas of cruelty and suffering in “Songteller” if she did not believe that this harsher strain in her life and work was worth remembering. Her optimism stands on the shoulders of pain.

Dorian Lynskey is a contributor to the Guardian and British GQ and the author of “33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs From Billie Holiday to Green Day.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.