David Byrne reveals ‘how the trick is done’ in HBO’s ‘American Utopia’

In at least one way, David Byrne was well prepared for quarantine.

From last October to this past February, the former Talking Heads frontman performed six nights a week on Broadway as the star of “American Utopia,” a theatricalized version of a touring concert he’d taken on the road behind his 2018 album of the same name.

Which meant that for about four months this longtime habitué of New York’s cultural scene essentially had no nightlife.

“Actors in shows can’t meet people for dinner, they can’t go out and see other shows or see music,” he said the other day. “You go to work at 6 o’clock, you come back home. Your life really changes.”

So when “American Utopia” closed in February (with plans to return to Broadway in the fall), Byrne, 68, was looking forward to reconnecting with the city and with his friends.

Then the coronavirus shut down every place he might’ve met them.

“It was like, Nope! Still can’t go out to dinner,” he said with a glum little laugh in a Zoom call from his home. Dressed in a faded Austin City Limits T-shirt, his dark glasses and floppy white hair as cool-professorial as always, he added, “I miss being around lots of other people. You don’t realize how big a part that is of who we are as human beings until it’s taken away.”

Eddie Van Halen, son of blue-collar immigrants, went to Pasadena High. David Lee Roth, his dad a doctor, attended Muir. Their meeting remade rock.

Indeed, Byrne fans from back in the day may be surprised to hear how important other humans are to the famously standoffish singer who took an electric lamp as a dance partner in Talking Heads’ iconic 1984 concert movie, “Stop Making Sense.”

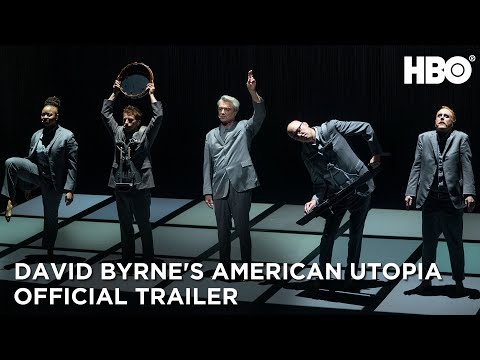

Yet the joy of togetherness undeniably suffuses a filmed rendition of “American Utopia” that premieres Saturday on HBO. Directed by Spike Lee, this new concert film based on the Broadway production presents Byrne as a kind of pep-talking philosopher leading a large and lively band — each member of which wears a tailored gray suit to match the singer’s and carries his or her instrument across the Hudson Theater’s empty stage — through a well-chosen set of Byrne solo cuts and Talking Heads classics including “Once in a Lifetime” and “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody).”

Inspired in part by recent tours by Kendrick Lamar and Beyoncé, the visually stark, lushly emotional concert also features a riveting performance of Janelle Monáe’s call-and-response protest song “Hell You Talmbout,” which Lee punctuates with stirring images of surviving relatives of Black people killed by police.

The night before our talk, Byrne — who’s now set to bring “American Utopia” back to Broadway in September 2021 — said he’d actually gotten out of the house to take in a drive-in screening of the movie in Brooklyn.

“People honked their horns instead of clapping,” he said. “And, you know, the sound can be great, depending on the system you’ve got. But you step outside your car, which you’re discouraged from doing, and it’s so weird — just silent.”

At the end of film, the camera follows you and your castmates backstage after the curtain call, and everybody’s hugging and high-fiving.

All these sweaty people. And everybody’s shouting. You go, Ewww — we don’t do that anymore.

Have you thought about how live music returns?

A little bit. I heard from the comedian John Mulaney, who came to our show a lot; he said he’s done a few stand-up dates either outdoors or in some situation where the audience is really spread out. He said it’s very strange, but it feels much more real than a Zoom performance.

Rock fans have been trained to think of a studio recording as the canonical version of a song. But there’s live stuff of yours from “Stop Making Sense” or “The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads” that feels just as definitive.

I agree. My default thing is to think of the recorded version as the official version, and then everything is based on that. But there were plenty of people at the Broadway show, I don’t know if they ever bought my last record. They would experience those newer songs live — as a performance, with the dance and the movement and the lyrics all together — and they seemed to love them.

When did you start thinking about a concert as something that could be thought through? As opposed to the more improvisatory experience we like to imagine.

Like a lot of other people, I was of the opinion that for a rock show to be authentic, you can’t have it all planned out. Choreography and patter — that’s not giving the real emotions to the audience. But in the early ’80s we were touring, and I went to see a lot of Asian theater in Japan and various rituals in Bali. I realized this is a kind of theater that doesn’t pretend to be an imitation of real life. And so the idea that theater should pretend to be naturalistic and gain its authenticity from that — well, that’s just not true. If I can do that in a way that really works, then I might actually make something that’s more emotional and engaging than if I simply stand there and sing my heart out.

You put a lot of thought into your appearance onstage. Do you think about it in real life?

Not so much. I took my grandson for a walk to the kiddie park this morning, and I sure didn’t dress up for that. But it is true that if it’s a public thing I’m doing, how you present yourself is a kind of performance. I mean, I’m not Lady Gaga. But there’s an element of theater to it, and to pretend there’s not — at some point, I realized you have to own it.

So many of your outfits and gestures have entered the bloodstream of pop culture. When something you’ve done becomes so highly referenced, does that change how you think about creating new things?

A little bit. When we started the tour, where we were all mobile, nothing onstage, just moving around all the time, I did think to myself, How can we go back to me singing with a bunch of musicians just standing there? How can anybody go back to that now that all this is possible?

Do you think the novelty of the approach is why the show has connected with such a wide variety of people?

I know word got out among other musicians and performers: “You may not love his music, but you gotta see what this guy’s doing.”

How’d you like wearing a headset microphone?

I’d done it once before, but it does take some getting used to. You’re never off-mike — you can’t turn your head and say some little comment to somebody.

The dreaded hot mike.

The transmitter’s on my belt, so I can reach over when I get offstage and turn it off. But yeah — we’ve all had moments of: Oh my God, I’m in the bathroom — is the mike still on?

Eighteen months ago, 24kGoldn was a business major finishing freshman year at USC. Today, he has a No. 1 hit with “Mood” and can afford to lease his own car.

Like “Stop Making Sense,” “American Utopia” allows the audience to see how the show comes together. Why does that appeal to you?

I like the idea of showing how the trick is done — but then doing the trick and it still gets you. Knowing how an effect is achieved doesn’t take away the magic.

Were you one of these kids who wants to find out how everything works?

I remember I had these British comics that my grandfather would send me. Every week they had a centerfold that was an exploded diagram of something — a jet engine or a battleship or a submarine — with a cutaway view of the whole thing. I would just pore over them.

You also keep coming back to the image of a bare stage.

It makes the show about the people. It’s not about the sets or the risers or the other things you’ve built around them. It’s about our bodies, our voices, maybe our instruments — that’s it. And we’re just like you in the audience.

How’d Spike Lee get involved?

At some point in the tour I thought the show might work as a film, because there’s a kind of thread through it, maybe an arc. Very early on I approached Spike — I had his number, so I just called him and said, ‘We’re doing the show in Boston. You want to come up and see what you think?’ Obviously I was aware of Spike’s work; we’d crossed paths many times and kind of came up in parallel in New York. The show hits on a number of issues that I thought were right in his wheelhouse. And it’s also in some ways an ensemble piece, which he does a lot — even as recent as “Da 5 Bloods,” where you get to know those guys and how they interact and how those interactions change over the course of the movie.

One thing that’s valuable about the movie is the close-ups. I liked seeing things I couldn’t make out in the theater or in a concert venue.

Me too. The first time I saw a cut of the film, I saw stuff that I’d either forgotten about or had never seen before.

In “Hell You Talmbout,” as various band members name victims of police violence, you personally sing the line about Amadou Diallo, whose killing I assume you remember well.

That was a pivotal moment in New York. Bruce Springsteen wrote a song about that killing. That was brave of him. Not everyone in his audience agreed with what he was saying there.

You don’t typically confront your audience with your views. But that’s very much Spike’s style. How did you think about those two approaches intersecting?

At that point in the film, the audience is ready for that more direct conversation. And it’s very moving. But it’s true — a lot of times I’m definitely more show-don’t-tell. I think it’s sometimes obvious what my feelings are, but I don’t put it out there; other than voting, I’m not telling people what to think. You’re all intelligent, you can make up your minds.

Have you reconsidered that tendency as American life has gotten stranger and more outrageous?

It’s still my guiding principle. In recent months and recent years, my sense is to be more engaged, but still keep things nonpartisan, let’s say. Maybe in my personal life, I do something else. But in my professional life, I keep it nonpartisan in hopes of bridging these divides, rather than just speaking to the converted.

Has doing “American Utopia” made you think that’s possible?

I can’t confirm that.

But it’s made you feel hopeful.

Yeah. The audiences love that we’re bringing up all these subjects — they tell me. Whether it changes people’s minds or makes them behave in a different way, I can’t say.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.