A-OK boomers: New ‘Laurel Canyon’ doc will make you swoon over the scene all over again

One of the most sacred musical places in the baby boomer bible sits just above the Sunset Strip in the once-ramshackle Laurel Canyon neighborhood.

The era’s own Garden of Eden, the labyrinthine neighborhood became a tangled nest of creativity that housed rising artists including Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Frank Zappa, James Taylor, Jackson Browne and members of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the Doors, the Mamas & the Papas, the Monkees, Love, the Eagles and dozens of other soon-to-be-famous artists.

Virtually every plugged-in American over 18 has been indoctrinated into understanding that musical history was made in the hills. Histories, memoirs, art books, a few documentaries and a fictional film — it would seem that the story of how a relatively isolated L.A. ZIP code helped connect artists with one another, who then connected with millions of fans, has been told.

“Really, we need another one?” Alison Ellwood, the director of “Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time,” a two-part, 3½-hour limited series that premieres Sunday on Epix, says with a laugh. “We did think a lot about that. But it was this truly magical bubble that gurgled up.”

More than most, Ellwood understands this. She also directed the 2013 documentary “The History of the Eagles.” Like that film, “Laurel Canyon” was produced Alex Gibney’s Jigsaw Pictures. Another of her L.A. music projects, “The Go-Go’s,” will premiere on Showtime in August.

For the first time in a century the Hollywood Bowl is closed for the season. Here, stars from Lionel Richie to Danny Elfman reflect on their favorite Bowl performances.

Bits and pieces of the Laurel Canyon story have certainly been told, Ellwood adds, but none had offered a grand look at the connections and relationships that fertilized the creativity, told entirely from the perspective of the participants. Fewer still have had the budget to afford the music licenses required to properly soundtrack the story. The Andrew Slater-directed, Jakob Dylan-guided “Echo in the Canyon,” which came out in 2019, mines similar terrain but is missing the volume of footage and music required for the kind of film Ellwood wanted to make. (“Echo...” is also missing any mention of Joni Mitchell.)

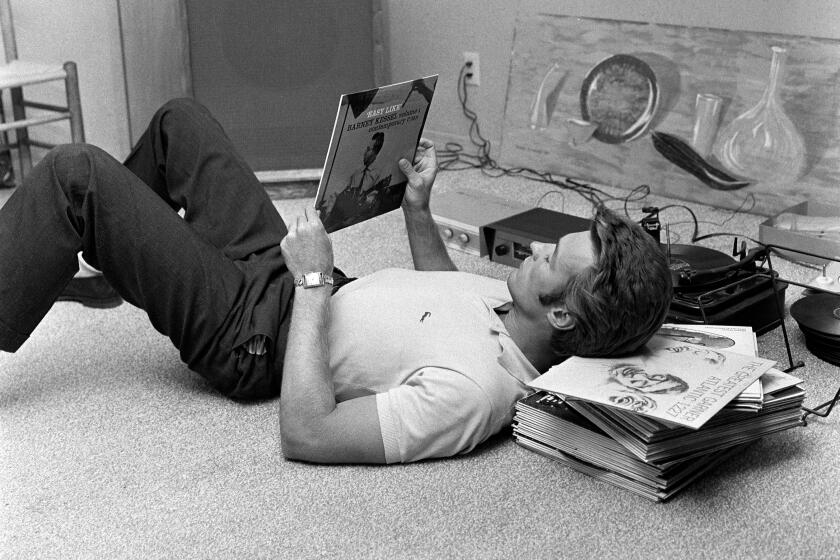

Ellwood’s “Laurel Canyon” corrects that. The most comprehensive and musically satisfying document of a notably insular scene, the limited series combines sublime performance footage, home movies, artist interviews, choice music and a host of images by two photographers present at the time, Nurit Wilde and Henry Diltz, to tell a vivid story of a period that took place roughly from 1966 to 1972.

A music scene that has been idealized to the point of redundancy, it’s represented in this film as akin to Paris in the 1920s, when the stars aligned to connect writers Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kay Boyle and Ernest Hemingway.

From an aesthetic perspective, it’s hard to deny. Mitchell wrote all of her album “Blue” while living with Graham Nash in the canyon. Nash composed “Our House” about their place. Stephen Stills wrote “For What It’s Worth” about the scene down below on the Sunset Strip, and the foundations of his and bandmate Young’s band Buffalo Springfield were laid in that soil. Nash, Stills and Crosby figured out that they could do three-part harmonies here. While living in the Hills, Arthur Lee and his band Love crafted “Forever Changes.”

This music suggested that the new decade might be a little more settled and bucolic than the one they’d all just lived through, like the sparkling afterglow of a particularly great acid trip. It also portended an easing into adulthood, and a desire to create music minus the “yeah-yeah-yeah” screaming and shouting, or the Jimi Hendrix-driven freakouts.

How to keep Coronavirus stress at bay: Listen, really listen, to your favorite albums, front to back, without distraction.

For those reasons and more, Ellwood, whose feature film directing credits also include “American Jihad,” “Spring Broke” and “Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place,” had been wanting to focus on the Laurel Canyon music scene for 20 years. A lifelong Doors fan, she was drawn to the neighborhood when researching a documentary on the band that never happened. Along the way, she made connections that convinced her that an untold tale lay beneath the surface.

Guided by photographers Diltz and Wilde, whose presence at regular intervals across the series helps anchor the structure, Ellwood’s narrators include David Crosby, Linda Ronstadt, Alice Cooper, Michelle Phillips, the Monkees’ Mickey Dolenz and Mike Nesmith and the Doors’ Robbie Krieger. Woven in are archival recollections from dead musicians including Love’s Arthur Lee, Zappa, Cass Elliot and Jim Morrison. Though neither Mitchell nor Young agreed to be interviewed for the film, Ellwood’s research team found illuminating archival interviews with both.

The first time Mitchell arrives in “Laurel Canyon,” she’s sitting on a stool preparing to be interviewed. Out of the frame, someone asks her to look into the camera and say who she is.

She looks a little surprised by the question. “Who I am?” Pondering for an uncomfortable moment, she says with a laugh, “That’s a hard departure point. A synopsis?” He means her name.

“She struggles with that for 35 seconds, and we let that run for that long,” Ellwood says. “To me, that’s who Joni Mitchell is. She always goes to the deepest possible place.”

The team’s goal was similarly intentioned, to create what the director calls “something immersive and experiential that included a lot of artists. [But] I didn’t want it to feel like an anthology. What magically happened for us, in the process of editing and researching was, we learned about all the ways the artists were very organically connected.”

That approach illustrates the reasons why Ellwood’s story is a crucial contribution to the canyon narrative. Peter Tork’s parties, the sidewalk meet-ups in front of the Troubadour, the flourishing of the Byrds, a teenage Jackson Browne’s arrival on the scene, the TV success of “The Monkees.” All combined to confirm the spot as a kind of Valhalla. Nostalgia has sanded off the rough edges.

Striking footage humanizes musicians including Morrison, who is shown during one fantastic snippet pedaling shirtless on a beach cruiser. Grainy footage of the Byrds’ first gigs at Ciro’s, and of a seated crowd at the Troubadour awaiting a folk concert, reveal hidden corners of the scene’s psyche.

“Laurel Canyon” lays it all out, combining narrative through-lines that in one way or another entangle Mitchell, Crosby, Stills, Nash, Gram Parsons, Ronstadt, David Geffen and his business partner Elliot Roberts, , John Phillips, Denny Doherty, Michelle Phillips and Elliot of the Mamas & the Papas, Gene Clark and various other members of the Byrds.

For example, Crosby used to lure friends to backyard concerts with what he calls “the best pot in town,” which would get them “completely stoned out of their gourds.” Crosby adds, “And then I’d say, ‘Hey Joni, why don’t you sing a song?’ They’d listen to her sing and their brains would run out their noses in a puddle, and that would be that.”

As with most L.A. music stories of the era, the Manson family makes a cameo to kill the whole vibe. Or maybe it was the rising mountains of cocaine.

Ellwood says the series arc was driven by “naivete and innocence, at the beginning, but a sort of darkness always comes into these things.” Specifically, the Hells Angels stabbing at the Rolling Stones’ concert at Altamont Speedway and the Manson family killing spree, both of which occurred in 1969, mark a turning point.

That shift was driven as much by the perils of, and drive for, success, as it was by Manson or Hells Angels. Even without those two oft-employed end-of-era touchstones, the scene was pricing, and drugging, itself out of the canyon. The union of neighbors Crosby, Stills and Nash begat a harmony trio that, after Woodstock, made them millionaires.

Music men Geffen and Roberts relocated to L.A. from New York to tap into the budding scene, and helped propel the careers of clients Young and Mitchell before founding Asylum Records in 1971. The label’s initial, and good-looking, roster of Browne, Mitchell, Ronstadt, J.D. Souther, Judee Sill and Glenn Frey all had canyon connections. Within a few years, all but Sill were household names, and the successful commercialization of hippiedom had made Geffen and Roberts millionaires. They sold the company a few years later.

With Warner Bros. signing canyon-dwellers Young and James Taylor and Lou Adler’s Ode working with Carole King, big labels advertised these young, beautiful singer-songwriters as being the product of Walden-esque respite. That each of these young men managed to elude a military draft that sent less fortunate souls to the front lines in Vietnam is little more than a footnote. The freedom of movement afforded the artists allowed for a bucolic privilege in which money is seldom an issue.

Ellwood traces the dissolution of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and offers the bittersweet story of how the Doors ended up signed to Elektra Records — seemingly at the expense of labelmates Love. Morrison’s antics get a lot of screen time, but his undeniable charisma is on full display. His death from an overdose doesn’t, of course, come as a surprise. Drugs were everywhere, and seemingly everyone in the canyon was dosed on acid, stoned or both.

Those polarities helped dictate a structure for the two episodes, Ellwood says. “The first part would be more of the light, and the second part would be more of the darkness. There’s tons of light that comes through the darkness in Part 2 as well — it’s not like it was doom and gloom. But it shifted.”

‘Laurel Canyon’

Where: Epix

When: 9 p.m. Sunday; concludes June 7

Rating: TV-MA (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 17)

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.