‘It’s like losing a family’: An L.A. nightclub and its workers fight for survival during the coronavirus outbreak

On March 12, Johnny Luna showed up for work at Lodge Room in Highland Park. The 33-year-old father of two is the lighting director for the club, a 500-capacity independent music venue right off a popular stretch of Figueroa Street. He runs the lighting boards at the Wiltern, the El Rey and other venues too, but that evening, he was booked to DJ in Lodge Room’s adjacent restaurant, Checker Hall.

Luna walked up the stairs at Lodge Room with his heavy crates of vinyl in tow. The former Masonic venue has an occult-ish vibe, with a mural of an ancient temple behind the stage and a five-pointed wooden lattice star and wrought-iron candelabras mounted above the dance floor. The venue is a favorite of goth-friendly acts like Billy Corgan, Death Valley Girls and Deerhunter. Phoebe Bridgers and Lawrence Rothman have played breakthrough sets there, and Dave Chappelle once dropped in for a surprise stand-up gig.

But fears of the coronavirus had been circulating all week, and the club’s usual crowds had thinned out. Only two people were in the restaurant. The venue’s general manager gave Luna a free dinner and sent him home.

When Luna got back to his place in Boyle Heights, he saw a deluge of panicked emails.

A Nobel laureate predicted China’s recovery weeks before it happened. Analyzing the numbers, he sees a much brighter global outcome than many experts.

“That’s when I started to get the mass cancellations,” Luna said. “I was starting to sweat a bit when I realized that all of March was canceled, and then by Saturday, we realized the whole industry would be shut down for the time being.”

The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 has changed the world in unfathomable ways since last week. All of California is under a safer-at-home order). Whole sectors of the local economy — entertainment, film, hospitality, nightlife — are locked down for an indeterminate amount of time. An economic recession is all but certain.

After the South by Southwest conference in Austin, Texas, was canceled and then Indio’s Coachella festival was postponed, it was obvious that the live music business would be deeply affected by COVID-19. This month, mega-promoters Live Nation and AEG hit pause on all its tours and festivals, but with deep coffers and expensive insurance policies, they will likely weather the storm.

But for the small-capacity, independent nightclubs that form the backbone of L.A.’s local music scene, the coronavirus is an unprecedented nightmare.

“The venues controlled by AEG and Live Nation will be fine. But smaller independent venues are going to be under strain,” said Patrick Adler, a researcher at the University of Toronto and a PhD candidate at UCLA who studies music festivals and the live-music economy. “Most smaller places don’t have one month of rent on hand, so two months will destroy them.”

While big-name celebs post treacly hymns of healing, upstart artists have created freaked-out, gallows-humored hip-hop and pop songs that better reflect our moment.

His data, compiled with University of Toronto colleague Richard Florida, suggest that L.A. concert promoters and artists will be more affected by the shutdown than any other city in the country. Southern California is the nation’s preeminent destination for major music festivals, with one in 10 in hosted here. Adler estimates that only 5% of promoters and 30% of artists can continue their careers in this environment, and they weren’t well off to begin with.

“The promotional workforce is on average very poorly remunerated, even in the best of times, with annual wages of $38,000,” he said. “So they are not only very exposed to this crisis, but they will probably feel it more.

“In short, they’re screwed,” he added, using a stronger adjective to describe the likely future for many small venues.

To get a sense of what they’re up against, The Times interviewed several of the 75-member staff at the Lodge Room, from the owners to the part-time bartenders. The club is emblematic of the kind of venue most at risk. Last year, the venue produced 178 shows and 42 private events, grossing $2.6 million, according to its owners. Lodge Room has three full-time staffers but can’t yet provide health insurance for employees. During the shutdown, as long as resources last, the venue’s talent buyer and general manager will draw a salary, but part-time employees have to wait until reopening for new paychecks.

To varying degrees, staffers are frightened for their business and their livelihoods. Many other club owners, sound engineers, talent buyers and barbacks around town are likely looking at the next few months without work, and they share those fears.

“This feels pretty catastrophic,” said Khalilah Pianta, 30, who works in a photo studio by day and tends bar at Lodge Room at night. She moved to L.A. a year and a half ago from Melbourne, Australia, like so many who flock here for L.A.’s nightlife and creative industries. She’d been doing well so far this year, but now, she says, “I’ve got like two months, max, of savings for basic survival stuff.”

Pianta just moved into a new apartment in nearby Lincoln Heights. She hasn’t bought furniture yet, and her living room will stay empty for now. “It’s going to be pretty barren here for a while,” she joked. “For me, the bar was a way to sustain myself while I pursued a creative career. But all my jobs have been canceled at the studio, and now my safety job has disappeared too.”

She’d been frantically applying for unemployment and jobs in whatever industries are still hiring — grocery store clerk, delivery driving, any freelance photo gigs that can be done from home. But the sudden shock to the economy has underlined just how precarious lives in creative industries are, even when times are good.

“I hope this shines light on how much these industries contribute to society,” Pianta said. “So many people in this industry have no money and no backup. When this is over, people are going to want to go out and eat and see music. But if no one can pay rent and survive, those places may not be there later.”

The latest updates from our reporters in California and around the world

In the meantime, live music professionals are trying to ride this out and stay sane. Luna said Lodge Room’s owner let him take the club’s lighting console home so he can practice new setups. The lights have made for some fun house parties with his kids, ages 14 and 9, who are home from school for potentially the rest of the term. Having their grandparents nearby for childcare has been essential.

“I’ve been getting in a lot of podcasts and piano practice,” Luna laughed. But the 20 or so gigs he usually books per month won’t be returning any time soon. “Everything I do professionally is at a standstill,” he said. “I’m not the best at saving money, so I’d be lying if said I wasn’t worried. Other venues I frequently work at are owned by corporate conglomerates. But Lodge Room is completely indie, so I’m more worried about that place. We’re all family there.”

The team behind Lodge Room is just as concerned, if still hopeful for the long term.

Dalton Gerlach opened Lodge Room in 2017, just as Highland Park was becoming the heart of the city’s live indie music scene. The 30-year-old’s family (along with three investors) co-owns the stately Masonic building that houses it, which helps for staying in business if there is a long closure. But there is a mortgage to pay, and while “lenders aren’t too friendly in such situations, this is unprecedented, and I hope we can defer things,” he said.

Gerlach said he feels the deep disappointment of sending his staff home until this blows over.

“We put some reserves aside, but we never thought we’d have to use them for this,” he said, adding that he estimated the club could hang on for four to five months in standby mode. “We’re optimistic we can stay around, but we had to do hard things like cut all hourly staff. Everyone’s kicking in to take reduced pay. Survival in this business is week to week and month to month even in good times. This is obviously much more dramatic.”

Gerlach has been working from home in Franklin Village with his girlfriend and managing the few things left while the club goes dark — giving out all the unsold food to employees and dealing with vendor contracts for the rest of the year. He fears what the social isolation will do for the morale of his employees.

“It’s strange, people don’t realize how much this means to us. Sometimes it feels like work is work, but when you don’t have it, it’s like losing a family.”

Raghav Desai, Lodge Room’s talent buyer, has been holed up with his dog in his Glendale apartment. “He’s a companion I never thought I’d need until now,” the 27-year-old joked. “He keeps me sane and allows me to escape the reality of the situation.”

That reality is an empty calendar and no prospect of booking shows until summer at the earliest. “South by Southwest canceling was a huge reality check,” he said. “A week later, it was Coachella, and that was like ‘Oh, OK. This is going to affect us.’ Then the government made their recommendations and it all unraveled. It’s been really weird. How does a venue exist when people aren’t allowed to go to concerts?”

Desai has been emailing artists and agents to try and hold dates for later in the year and figuring out how to refund fans who bought tickets in advance (he hopes that most will hang onto tickets for reschedulings). But as the point of contact for the artists who pass through Lodge Room, he’s more nervous about how they’ll hold on.

“I’m worried about the bands,” he said. “So many livelihoods are affected by this: tour managers, audio engineers, bartenders. What’s going to happen to them?”

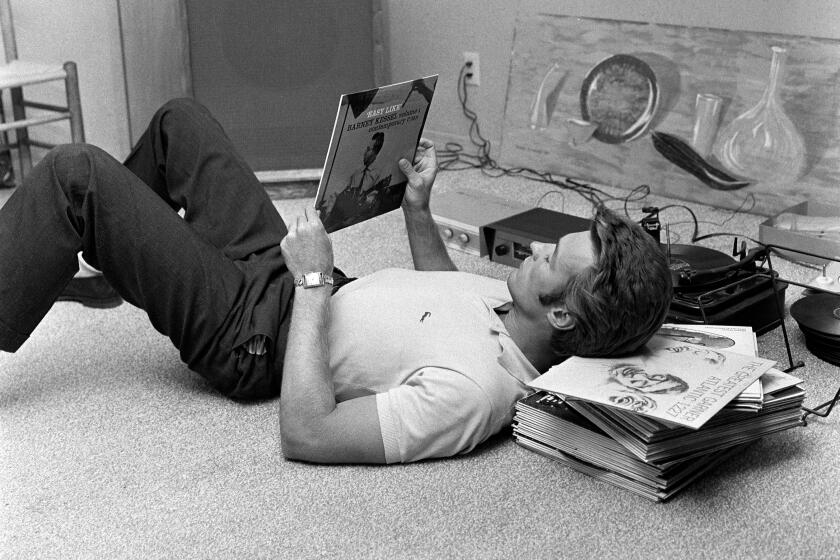

How to keep Coronavirus stress at bay: Listen, really listen, to your favorite albums, front to back, without distraction.

For now, Lodge Room staffers agreed that an immediate economic stimulus — preferably a check, right now — would be the most useful way to sustain livelihoods.

“A rent freeze would also be so important,” Pianta said. “That’s the biggest overhead while everything’s shut down. Big industries are losing money, but they can still afford to pay people. We need money for small businesses and the freelancers who can’t get by. Where do you go find work when there isn’t any?”

Luna, like everyone interviewed, didn’t expect much help from the Trump administration but held out for L.A. or California to recognize how important nightlife and entertainment are for the state’s economy. He was clear on what he needed to survive. “A rent moratorium, mortgage moratorium and utility bills on hold,” Luna said. “We’re a resourceful bunch, but keeping our residence is the thing that worries me most.”

Cobra and Chico go-go dancers and others are appearing on a subscription stream with proceeds going to Team Cobra/Chico Relief Fund for Team Members.

In wake of the closures, the Recording Academy’s MusiCares foundation announced a $2-million relief fund to help artists and music industry professionals affected by the pandemic, as have Sweet Relief, Music Fund of L.A. and the American Federation of Musicians. A number of other organizations are also features on this resource list for freelance artists.

The practicalities of surviving in nightlife these days are frightening enough. But the loss of identity that comes from being shut in will take its toll too.

A life without live music, without hugging friends and sharing drinks while a favorite new band performs has costs you just can’t quantify.

“You build a world around this thing you do,” Desai said. “It’s not just work. Being out with people you know, the idea of a community — I’ve built my life around that for six years. When that shatters, now what?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.