We went face-to-masked-face with viral sensation RMR and it was ... strange

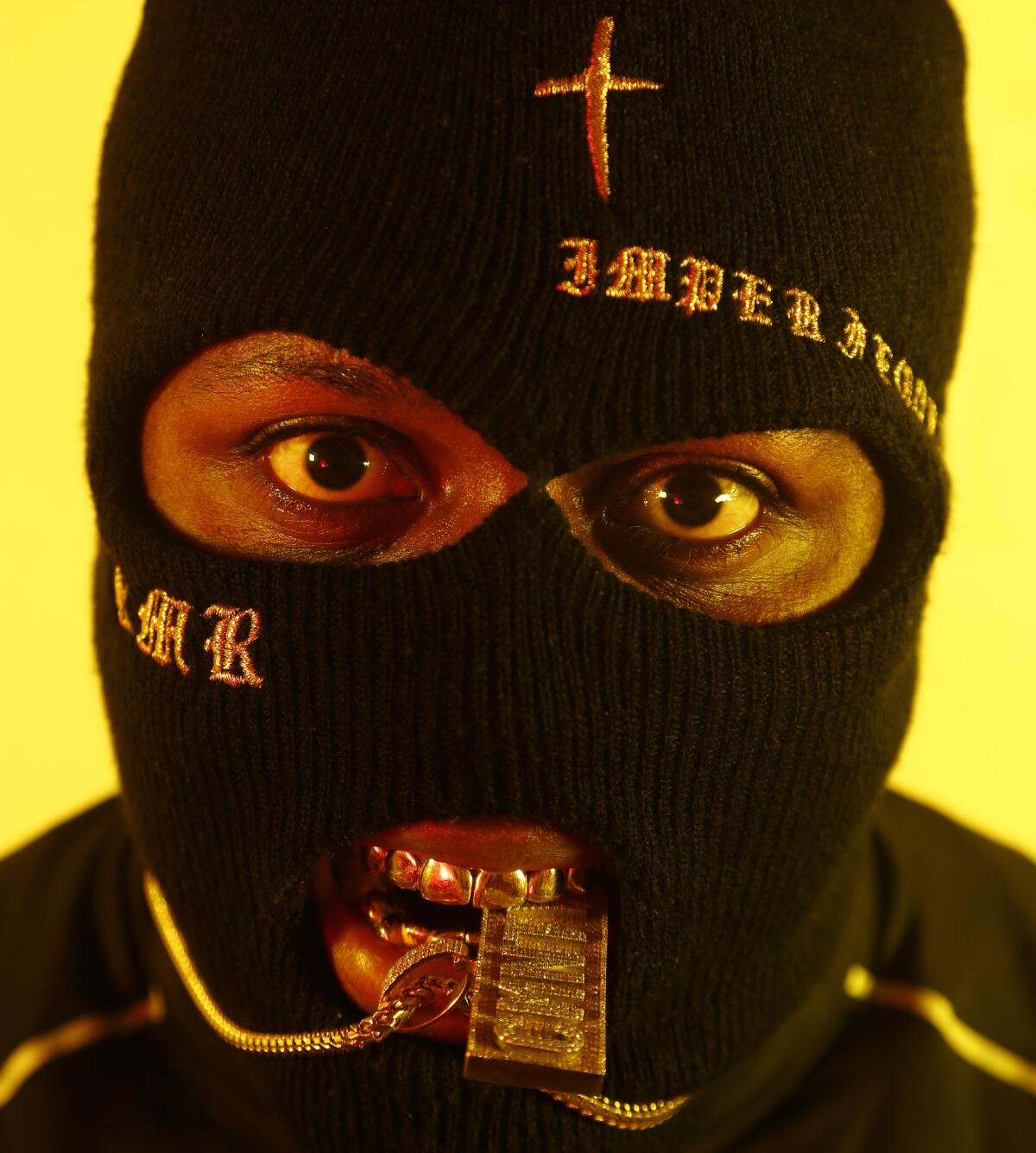

The self-styled enigma known as RMR entered the darkened recording studio, extended a soft but meaty hand and, from beneath a black balaclava, launched without warning into a passionate a cappella rendition of the traditional folk song “Man of Constant Sorrow.”

As first impressions go, it made for a strong one. But then striking introductions are quickly shaping up to be RMR’s specialty.

Late last month this previously unknown singer set a corner of the internet ablaze with the out-of-nowhere music video for his song “Rascal,” in which RMR (pronounced “Rumor”) — his face obscured by the same ski mask he wore the other morning in an interview at the Record Plant in Los Angeles — delivers a stirring, lightly modified version of Rascal Flatts’ “Bless the Broken Road” while surrounded by similarly attired men pointing fearsome, loaded-looking guns at the camera.

That’s the simplest way to describe the clip, but it hardly captures how startling it is to behold. Sure, the visual presentation — tattoos, diamonds, a Saint Laurent bulletproof vest — is in keeping with any number of modern hip-hop videos; ditto some of RMR’s lyrical tweaks, which transform Rascal Flatts’ romantic country hit (itself a cover of the lesser-known original by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band) into the tale of a cop-dodging drug dealer. Yet the piano-ballad arrangement and the singer’s yearning vocal performance cling tightly to Nashville convention, making for a potent juxtaposition that’s led many on social media to wonder if “Rascal” might be the next “Old Town Road” — and RMR, whoever he is, the next Lil Nas X.

Despite, or perhaps because of, its instant viral success, the official “Rascal” video disappeared from RMR’s YouTube channel almost as suddenly as it appeared, the apparent result of a copyright claim by Universal Music Publishing Group, which partially controls “Bless the Broken Road.” (A UMPG representative didn’t respond to a request for comment.) On Monday the clip quietly returned before disappearing again; the song remains available on Spotify, where it’s racked up more than 800,000 streams amid a valuable whiff of controversy not unlike that which enveloped “Old Town Road” after it was infamously booted from Billboard’s country chart. Among those who’ve publicly expressed their enthusiasm are Desus & Mero, the hip-hop tastemakers with a Showtime comedy series, and producer Timbaland, who was blending country music and rap back in the early 2000s in his work with Bubba Sparxxx.

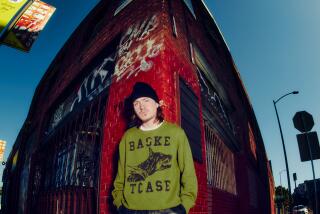

At the Record Plant, RMR — a solidly built black fellow who seems to be in his mid-20s — declined to address the rights issues or the YouTube takedown, nor would he state his real name, his age or much about his background (though he did agree to play some impressive unreleased music). In addition to the ski mask, he wore black pants and a black raincoat; when he smiled, his gold fronts glinted just as they do in the “Rascal” video.

So does he consider himself a country musician? “I like the term ‘music,’” he answered, his vaguely Southern-accented voice a bit gruffer in conversation than when he’s singing. “Music is music, whether it’s country, whether it’s blues, whether it’s hip-hop, whether it’s R&B. It’s music.” He said he grew up “listening to everything” and that God had shown him Rascal Flatts along with Jay-Z and Nas and Nelly and “Man of Constant Sorrow.”

Asked where he grew up, he said, “The world.” Rolling Stone, which recently talked to RMR by phone, said that as a kid he’d bounced between Atlanta and Inglewood. Is that true? “Everywhere between there,” was his gnomic reply. “From Georgia, you go all the way east around the world, you end in L.A.,” he added. “Then you keep going east, you end up in Georgia.”

We can assume, then, that he’s well-traveled?

“The world,” he said again.

Where did he sleep last night?

“The world.”

Does he have a family — maybe a brother or a sister?

“You.”

Asked when he started singing, he said when the “Rascal” video came out, meaning less than two weeks ago.

RMR’s anonymity stems from a couple of different desires. For starters, he said, “I want you to listen with your ears instead of your eyes. The world’s prejudiced. Preconceived notions.” He asked what a blind man would see if he heard “Rascal” — and what a deaf man would hear if he saw the video.

OK, so what he’s trying to do —

“I’m not trying to do anything,” he cut in. “I’m just doing music.”

RMR was accompanied at the studio by several members of his team, and here one of them — Malik Rasheed, president of RMR’s newly founded L.A.-based record company, CMNTY RCRDS — piped up to say that another reason the singer isn’t revealing his identity is because “he wants to have his life.”

“The hip-hop Marshmello,” added RMR’s manager, Adrian Swish, referring to the EDM star unrecognizable to many without his trademark headpiece. Then he, Rasheed and RMR rattled off a list of other artists who’ve chosen not to show their faces, including Sia, Daft Punk, Banksy and the folks behind Gorillaz (even though everybody knows they’re Damon Albarn and friends).

What they didn’t mention is that we’re actually living in something of a masked moment: On TV, “The Masked Singer” and Netflix’s hit “Love Is Blind” — in which couples “date” without seeing each other — are thinking through the relationship between communication and identity, and how that relationship might be changing in the era of social media. Part of the narrative tension in those shows comes from the promise of an eventual unmasking. Yet Rasheed insisted that RMR’s disguise is no temporary gambit, which means his music will have to deliver a complete emotional experience on its own.

The high-profile reference points provide some indication of RMR’s commercial aspirations, which he hopes to achieve with assistance from the well-placed music-industry veterans at CMNTY. In addition to Rasheed, a former A&R exec at Epic Records and Scooter Braun’s SB Projects, the team includes Michele Harrison, an experienced talent manager who’s worked with Vampire Weekend and Alanis Morissette, and Chief Johnson, who oversees entertainment marketing at Puma. Unlike the others, CMNTY’s remaining principal, Philip Lawrence — known for his Grammy-winning songwriting and production work with Bruno Mars — wasn’t present at the Record Plant, a storied creative hot spot that Lawrence purchased in 2016.

“How are you, honey?” Harrison asked RMR when she greeted him before the interview. “It’s good to see you — or not see you.”

Rasheed said CMNTY is looking to partner with a major label to release RMR’s music going forward; last month, Swish tweeted a photo of him and the singer at what appeared to be the offices of Columbia Records, with the caption “Good Meeting Today.” (A rep for the label, which helped drive the “Old Town Road” phenomenon, said she had “nothing to share or confirm” regarding RMR.)

At the studio, where a fruit plate had been set out as though this strange encounter were just another business meeting, the singer played two tracks from his phone, both of which he said he wrote and performed; he declined to say who produced them. The first layered lyrics about someone with a Percocet addiction over a dramatic R&B arrangement built around a repeated banjo lick.

“There’s an entire drug epidemic that’s going on right now,” RMR said when the tune was over. “And in the song, if you’re listening, it’s about a struggle — a man struggling with drugs.” Asked where the story came from, he said, “God.”

The other song he said was called “Nouveau Riche,” which he added was French for “New Money.” It had a hypnotic, slow-rolling hip-hop groove and mentioned Beverly Hills and a Patek Philippe watch. As the track played, RMR closed his eyes and sang along, his voice trembling with a kind of desperate pride. Afterward he offered an uncharacteristic sliver of personal context.

“I don’t come from money, so this is new money — first-generational wealth,” he said. “I’m talking about my experience that’s about to happen.”

Added Rasheed: “So many artists try to dictate with interviews and other things what the audience should hear.” RMR, in contrast, wants to leave it up to the listener.

Was there anything else RMR would be willing to play? Rasheed, who claimed an EP by the singer was due “very soon,” asked RMR if he wanted to play a song called “Welfare.” The singer began fiddling with his phone but within a few seconds evidently decided against it. Mystery had served him well so far, he seemed to conclude, and with that he stood, stuck out his hand again and said thanks for coming.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.