Appreciation: Ric Ocasek and the Cars’ gleaming new wave did something surprising: It endured

It’s almost impossible to do now, after decades of continuous radio play that’s rendered the Cars’ music as familiar as the smell of your own automobile. But put on “Just What I Needed” or “Let’s Go” or “Shake It Up” and try to imagine that you’re encountering the song for the first time.

Listen to the guitars, how they idle for a few seconds before suddenly zooming off from the starting line. Listen to the beat, which suggests a machine until it doesn’t. And listen to those crisp, compact melodies, none with a single note out of place — even (or especially) the weird ones, as when the dissonant “your” in “ribbons in your hair” gives “Just What I Needed” a vivid splash of sexual desperation.

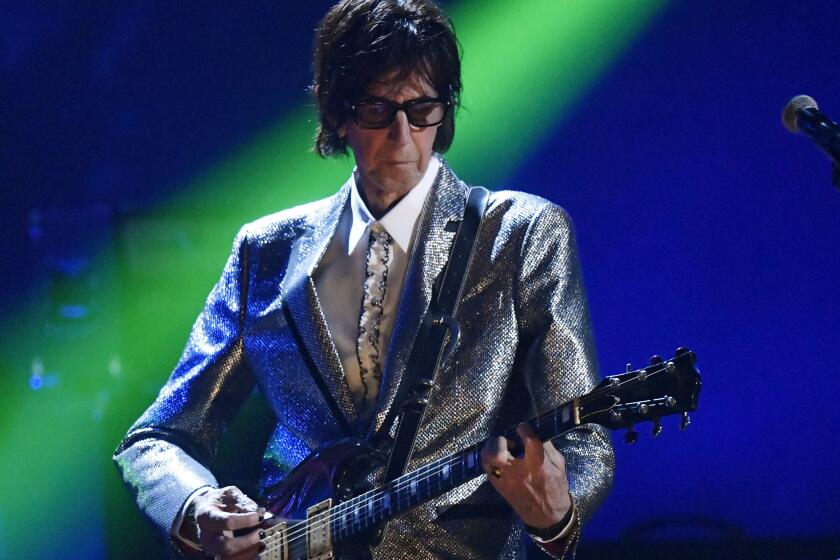

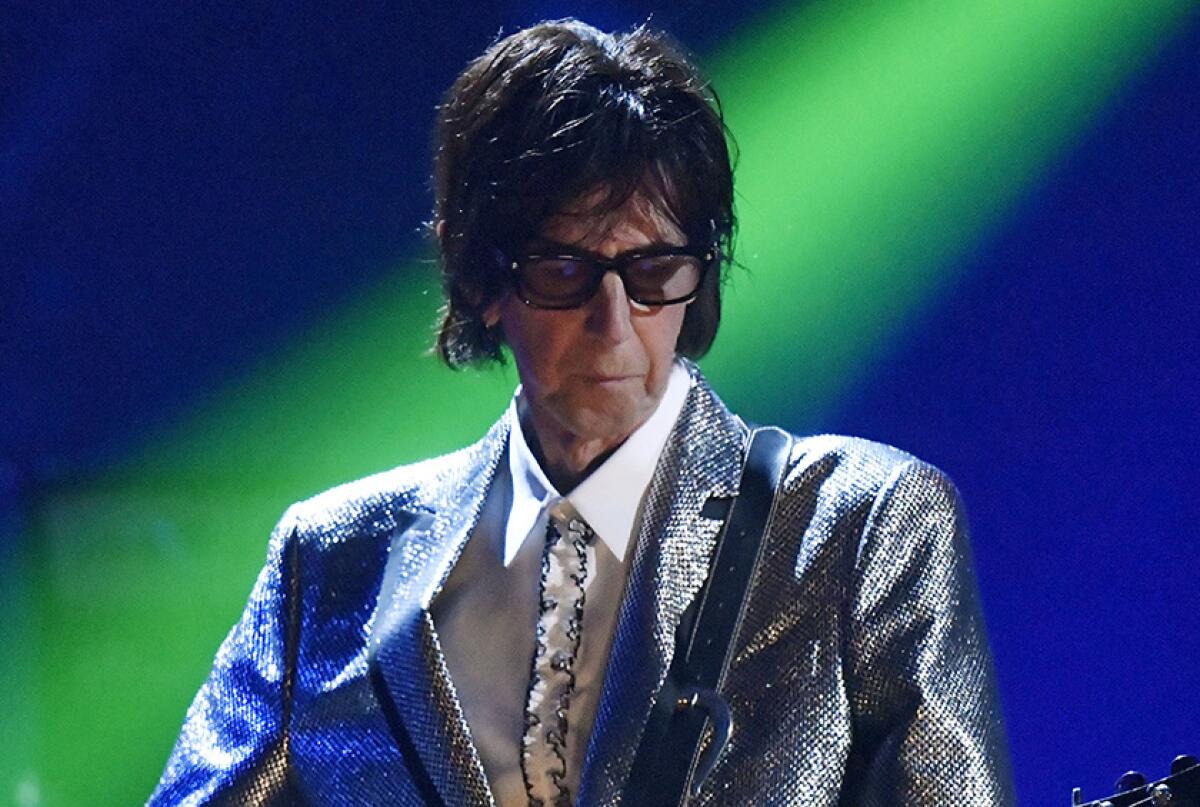

Do all that, then ask yourself if anybody from the late 1970s and early 1980s was making tunes more precisely designed to grab than the Cars, whose mastermind, Ric Ocasek, died at his home in New York City on Sunday, of heart disease. Depending on whom you trust, the eternally gangly Ocasek was either 70, which is surprising to learn, or 75, which is totally insane.

Obituary: Ric Okasek, the singer, guitarist and songwriter for the Cars, helped define the sound of the angled-haircut 1980s with songs including “Just What I Needed,” “Shake It Up” and more.

The poppiest punk band — or were they the punkiest pop band? — of their new-wave generation, the Cars grabbed plenty with their string of immediately appealing hits, more than a dozen of which made it inside the top 40 of Billboard’s Hot 100. From the group’s flawless self-titled debut album in 1978 to “Heartbeat City” in 1984, they went platinum every time out; their clip for “You Might Think” was named video of the year over “Thriller” at the inaugural MTV Video Music Awards. (Alas, the Cars lost best new artist at the Grammys in 1979 to, uh, A Taste of Honey.)

Yet Ocasek and his bandmates — guitarist Elliot Easton, keyboardist Greg Hawkes, drummer David Robinson and bassist Benjamin Orr, who died in 2000 — also knew how to maintain their grip. “My Best Friend’s Girl,” “Good Times Roll,” “Magic,” “Drive” — each hooky little jam stuck around to become a permanent fixture of the era, not unlike the less stylish singles of that other inescapable AOR figure who just preceded Ocasek in death: Eddie Money.

Look under the hood and you can understand why. Beneath the shiny surfaces and the metronomic grooves, the Cars’ songs, which Ocasek wrote and which he and Orr alternately sang, sported all kinds of musical and emotional eccentricities that made them hard to shake.

Think of that line about the hair ribbons in “Just What I Needed,” which cuts against the practiced indifference of the priceless opening lyric: “I don’t mind you coming here / And wasting all my time.” Or the unexpected moment Ocasek chooses to enter “Good Times Roll,” seemingly off beat until you finally grasp where he is in the rhythmic pattern.

Or consider how little the plush production of “Drive” sets you up for the sheer hopelessness of the song, the second-most-haunting ballad ever sung by a rock group’s bassist after Timothy B. Schmit and the Eagles’ “I Can’t Tell You Why.”

“Who’s gonna pay attention to your dreams?” Orr sings, “And who’s gonna plug their ears when you scream?” It’s a chilling vision made only more so by the loveliness of Ocasek’s melody.

The frontman — memorably captured in a late-’70s Rolling Stone profile, bitching about the lousy songs on his car’s FM radio — worked hard to create music that could tell both a short story and a long one. He and Orr formed the Cars in Boston after trying out a variety of other modes, including post-hippie folk-pop in a group called Milkwood. And the band’s graduation five albums in from Queen’s producer (Roy Thomas Baker) to Def Leppard’s (Robert John “Mutt” Lange) demonstrated Ocasek’s willingness to do Big ’80s bombast even as his lyrics grew colder and more suspicious.

The Cars’ heavy investment in music videos was another play for ubiquity by a band whose stiff live show never inspired much in the way of hysteria. Where some of his post-punk peers dismissed the medium, Ocasek went all in with high-concept videos for “Magic” and “Shake It Up” and “You Might Think,” which won that VMA with computer-generated graphics as garish as they were novel.

His understanding of the importance of visuals — here was a guy with a durable look — extended to his licensing the group’s music to movies, as when “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” used “Moving in Stereo” to soundtrack an iconic scene featuring Phoebe Cates.

Yet Ocasek’s commercial instinct was always accompanied by the commitment of a true artiste. During the Cars’ chart-topping heyday he produced uncompromising albums by acts like Bad Brains and Suicide; later, after the band broke up (but before it reunited briefly in 2011), he worked in the studio with some of its inheritors, including Weezer and Guided by Voices.

In 1997, another admirer, Billy Corgan of Smashing Pumpkins, convened a portion of Ocasek’s celebrity fan club to back the singer on a solo album clearly meant to attract a young new audience. The so-so “Troublizing” didn’t quite work out that way. But then it didn’t really have to: Last year, when the Killers’ Brandon Flowers inducted the Cars into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, he recalled being knocked out by the band’s classic records as a 13-year-old in 1994, well into its afterlife.

Ocasek’s instant hits had hung on. They’re still hanging on.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.