Barry Manilow lets the schmaltz do his talking at Hollywood Bowl

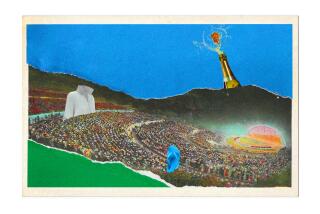

“God, you’re a romantic crowd,” Barry Manilow said approvingly from the stage of the Hollywood Bowl on Friday night. The veteran pop singer known for his lovey-dovey ballads had just belted one of the lovey-dovey-est of them all, and as he looked out at the thousands of excited middle-aged fans before him, he gave a little shrug to assure us he got it. “It’s a romantic song,” he said of “Weekend in New England,” in which the thought of a couple’s reunion makes the narrator’s blood flow. “I was turning myself on back there.”

The line was just one of the many well-practiced quips with which Manilow, a proud steward of the age before rock ’n’ roll, expertly peppered the first of two weekend concerts. But it wasn’t the certainty that he’d repeat the joke the next night that made you wonder if he actually meant it.

At 76 years old, Manilow is speaking more frankly than many show-biz lifers do about a career that in his case he insists he didn’t want. In a recent interview with the New York Times, the songwriter — who’s long claimed that he started singing only to get his material heard — said he “never” had a good time when onstage. That report was followed by a gossipy item from the New York Post’s Page Six that said Manilow was furious at his manager (who’s also his husband) for booking a three-week Broadway engagement this summer.

The picture that emerges, four years after what Manilow described with excitement as his final tour, is of a guy now putting on his bedazzled lion tamer’s jacket just to punch the clock.

Yet if he’s truly miserable up there, he did an exemplary job of hiding it during Friday’s show, a crisply paced survey of his splashiest and schmaltziest hits — the pleading “Mandy” as well as the campy “Copacabana (At the Copa)” — in which he was backed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. No, he didn’t scowl at anybody (assuming that remains a possibility on his conspicuously unlined face) or flip over his piano bench. But you wouldn’t say he was enjoying himself exactly; there was nothing loose or spontaneous or even especially cheerful about his act, particularly compared with the laugh-a-thons put on these days by peers such as Bette Midler and Lionel Richie. Rather, he appeared to accept that he had a job to do — and that getting the job done can be a valuable source of satisfaction.

Part of his work, as Manilow seems to understand it, is pointing out the perceived shortcomings of his successors on the pop chart. Not long into the concert, he bemoaned the fact that “today’s radio has no melody” — an absurd position, of course, but all the motivation he needed to haul out the undeniably tuneful “Looks Like We Made It,” whose seamless blend of crooner-era theatrics and plush adult-contemporary sonics offered a reminder of how emotionally legible love songs used to be.

As a counterculture refusenik, he also seemed to want to defend against the hippie-centric idea that pop is cheapened by its commercialism. At one point, he played two of the indelible jingles he’s written, for Band-Aid and State Farm, without the least bit of embarrassment; indeed, his surprisingly passionate rendition of the latter led directly to his recollection of the beginnings of his recording career — “back in 1821,” he said — as though the years since had given him little reason to see a difference between writing well about car insurance and writing well about love.

The drawback to Manilow’s coolly effective professionalism was that it left you unsure of his personal investment in his music. We’ve been trained to think of pop songs as illuminating singers’ inner lives, but here it was anyone’s guess if “Even Now” or “I Made It Through the Rain,” both delivered in a voice only slightly less creamy than in his heyday, still touch anything like a nerve. That he made no mention of coming out in 2017 — after decades of public speculation about his sexuality — suggested he wasn’t exactly burning to connect any dots.

For Manilow, perhaps, it was enough to give us our money’s worth — to hold up his end of an old-fashioned deal. He writes the songs; we pay his bills.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.